Installation view

Installation view

OMUAMUA MOONLIGHT, 2023, egg tempera and ink on canvas, 30 x 50 cm

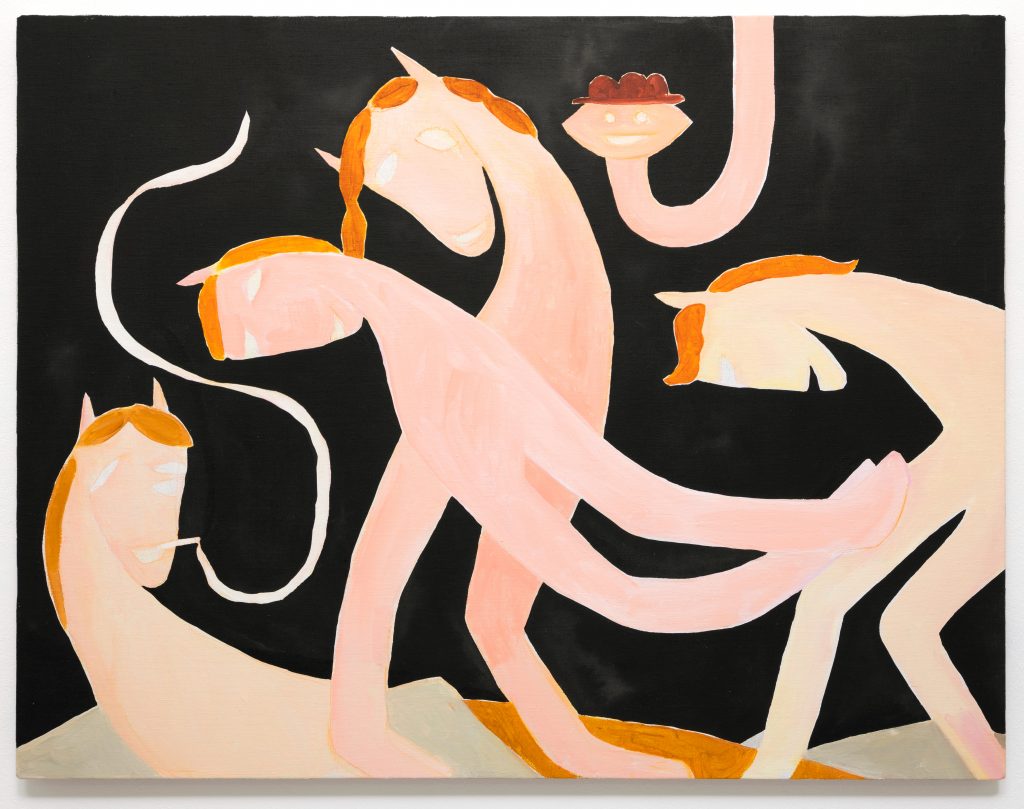

GROßE GARDE, 2023, ink, gesso, acrylic and egg tempera on canvas, 200 x 230 cm

Installation view

KLEINE GARDE, 2023, ink, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 82 x 105 cm

Installation view

Installation view

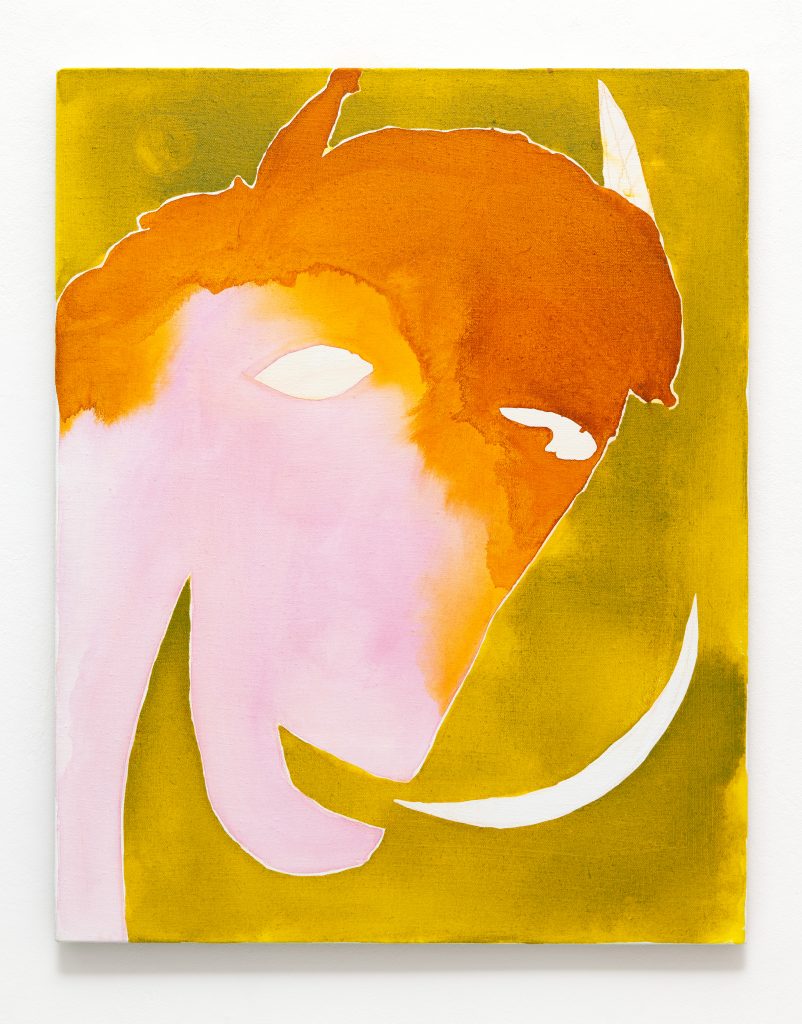

GRÜNER GARDIST, 2023, ink and gesso on canvas, 70 x 55 cm

HELLER GARDIST, 2023, ink and acrylic on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

Installation view

KLEINE VENERE, 2023, egg tempera, ink and acrylic on canvas, 50 x 24 cm

Installation view

ORANGE FREUNDE, 2023, egg tempera, ink and gesso on canvas, 54 x 45,5 cm

GRAUER GARDIST, 2023, egg tempera, ink and gesso on canvas, 54,5 x 45 cm

KLEINE MILCHSTRAßE, 2023, egg tempera, ink and gesso on canvas, 24 x 69 cm

Arrière Garde

Avantgarde die Vorhut, Arrière Garde die Nachhut? Wer an ein Heer denkt oder genauer an das Dreieck Kandinskys, richtet sich nach der Spitze, gerade dann, wenn sie oder er an der Basis steht, in einer Reihe mit Vielen. Aber Avantgarde wie Arrière Garde sind zum Hüten bestimmt, destinées à garder.

In Sarah Bogners Bild Große Garde nähern sich vier Kreaturen zusammen dem Dreieck, oder sie bilden das, was die Renaissance eine Figura piramidale genannt hat. Vom unteren Rand ragt ein Berggipfel, vom oberen Rand hängen links und rechts Rechtecke wie weiße Tücher, so dass der orangene Grund nur in der Mitte oben sich lichtet und nur einem Kopf Raum gibt. Wer will, kann die ganze Leinwand als Siegerpodest mit Relief lesen. Näher liegen die Treppen links und rechts und der oberen Durchgang, die Sarah Bogner in das Bouelles Bild eingeschrieben hat in Milchstraße 4. Aber aus vier wird nicht einfach drei, zwei Köpfe beugen sich vor dem einen ganz oben, das Dreieck läuft unten links aus in ein Wesen, ruhend und rauchend hinter dem Berg, und endlich wird das, was buchstäblich sich konzentriert, von einem Freund mit Hut gestört, der vom rechten Bildrand her kommt wie ein Rammbock.

In der nicht einmal halb so großen Kleinen Garde ist die Figura piramidale mehr in die Breite gezogen, ein Pferd mit Ohren, die in der Horizontalen wie Hörner wirken, dringt von rechts ein, der Freund mit Hut behauptet sich auf einem langen Hals, der von oben ins Bild sich windet, und erst recht windet sich der Rauch aus der Zigarette des linken Pferdes in einer eleganten S-Kurve, die nur den schwarzen Raum zwischen den Figuren von unten nach oben durchläuft. Wie in der Großen Garde wird die Figur, die die Spitze behauptet, zur Vierbeinerin erst durch ein zweites Wesen, das sie überlagert. Und sie findet sich wieder, freigestellt auf einem viel kleineren Format, als Kleine Venere. Sarah Bogner trifft sich scheinbar mit Lucas Cranach.

Aber Frau und Mann sind so wenig eindeutig zu lesen wie der Tag der Großen und die Nacht der Kleinen Garde oder die Formation in den großen und die Isolation in den kleinen Formaten. Es verhält sich doch anders, wenn das gefühlt kleinste Bild, das Sarah Bogner in der Galerie Christine Mayer zeigt, an ihr derzeit größtes Bild in Milchstraße 4 erinnert. Die Kleine Milchstraße reproduziert trotzdem nicht das Bouelles Bild, sondern sie wiederholt es. Der schwarze Mond in Omuamua Moonlight kann an die gesprochene Sichel des Grünen Gardisten erinnern, der Graue Gardist wie ein Porträt des rechten unteren Pferds im Bouelles Bild wirken, die Orangen Freunde, die nicht orange sind, den orangenen Grund der Großen Garde als figürlich behaupten. Die Wiederholungen stellen nicht Übereinstimmungen her, sondern Abweichungen.

Aber was immer anders erscheint, kommt doch nicht wie verstreute Gliedmaßen, disiecta membra zu liegen. Deren Zusammenhang war in dem Atlas aus Bildern, der Mnemosyne, Erinnerung heißt, historisch zu rekonstruieren. Und auch wer an Sokrates denkt und das weibliche Schauspiel sehen will, nachdem das männliche auch in der Kunst vollständig aufgeführt worden ist, muss diese Erinnerung erst wiederholen als Arrière Garde. 1843 sagt Sören Kierkegaard: „Die Erinnerung ist die heidnische Lebensbetrachtung, die Wiederholung die moderne.“

Berthold Reiß

Arrière Garde

Is the avant-garde the vanguard and Arrière Garde the rearguard? Whoever thinks of an army or, more precisely, of Kandinsky’s triangle, looks from below to the top, and they do so in a row with many others. But the avant-garde, like Arrière Garde, is destined to guard, destinées à garder.

In Sarah Bogner’s Große Garde four creatures approach the triangle together, or form what the Renaissance called a figura piramidale. A mountain peak protrudes from the lower edge while rectangles hang left and right from the upper edge like white cloths, so that the orange background thins out only in the top middle area of the picture plane and gives room for only one head. If you like, you can read the whole screen as a winner’s podium with a relief. Closer are the stairs to the left and right and the upper passage that Sarah Bogner inscribed in Bouelles Bild in Milchstraße 4. But four do not just become three; two heads bow in front of the one at the top and the triangle turns into a creature at the bottom left, resting and smoking behind the mountain, and finally, that which is literally materialising in a concentrated form is disturbed by a friend with a hat who enters from the right edge of the picture like a battering ram.

In Kleine Garde, which is not even half the size, the figura piramidale is more elongated. Here, in the horizontal plane, a horse with ears that look like horns enters from the right, the friend with the hat maintains himself on a long neck writhing into the picture from above, and the smoke from the left horse’s cigarette is curling up from the bottom to the top in an elegant S- curve that only runs through the black spaces between the figures. As in Große Garde, the figure that occupies the top becomes quadruped through a superimposed second being. And she finds herself again, cut out on a much smaller format, as Kleine Venere. Sarah Bogner seemingly meets Lucas Cranach.

Yet, woman and man are just as ambiguous to read as are the day of Große Garde and the night of Kleine Garde, or the formation of the large and the isolation found in the small formats. Sarah Bogner consequently denies this by referring the picture that feels like the smallest in Galerie Christine Mayer to her currently largest work in Milchstraße 4.

However, Kleine Milchstraße does not reproduce Bouelles Bild but repeats it. The black moon in Omuamua Moonlight may evoke the spoken crescent in Grüner Gardist, Grauer Gardist is reminiscent of a portrait of the horse to the lower right in Bouelles Bild, and the friends in Orange Freunde, who are not orange, claim the orange background of Große Garde figuratively. The repetitions do not create correspondences, but deviations.

But whatever appears different does not come to rest like scattered limbs, disiecta membra. Their connection was to be historically reconstructed in the atlas of images, called Mnemosyne, Memory. And even those who think of Socrates and want to see the feminine play, after the masculine play has been fully staged (also in art), must repeat this memory first as Arrière Garde. In 1843 Sören Kierkegaard says: “Memory is the pagan view of life, repetition is the modern.”

Berthold Reiß

Translated by Melanie Waha