Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

The Harboring, 2024, oil, pigments and distemper on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

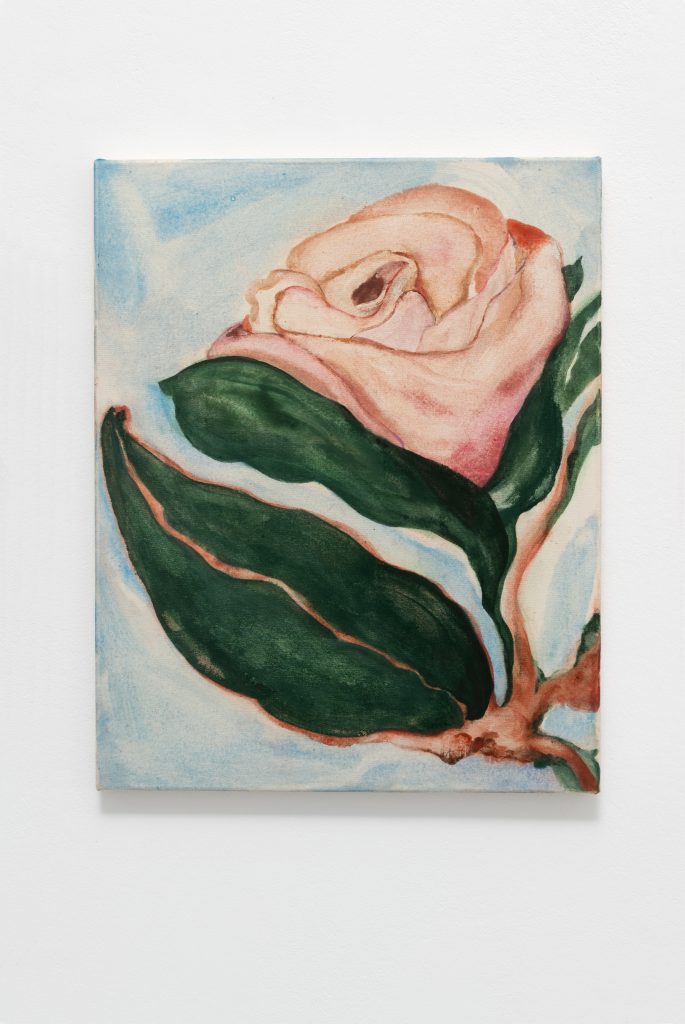

The Shy One, 2025, pigments and distemper on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

Installation view

Installation view

The Assertive, 2025, pigments and distemper on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

The Reliant, 2025, oil, pigments and distemper on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

The finest things thrive in dirt, 2023, oil, pigments and distemper on canvas, 50 x 59 cm

Flowers never pick themselves, 2021, ink on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

Untitled, 2025, pigments and distemper on linen, 30,5 x 23 cm

Installation view

The Insuring, 2025, pigments and distemper on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

Untitled, 2025, oil, pigments and distemper on polyester and wood, 25,5 x 20 cm

Installation view

Untitled, 2025, pigments and distemper on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

Granny‘s U.F.O., 2021, ink on canvas, 40 x 30 cm

MISTRESS OF GOOD ADVICE

On sultry Sunday evenings,

faithful only to yourself

we tell many stories with many endings

Lightning in the summer rain maintain facades,

everything is fleeting lalalalalala

You, or maybe not You

All flowers wilt differently,

all of them are good at keeping secrets, and they never pick themselves

Paula Kamps

PAULA KAMPS

Born 1990, lives and works in Cologne and Chicago

EDUCATION

2015 – 2016 Kunstakademie Düsseldorf with Elizabeth Peyton

2015 Meisterschülerin with Tomma Abts Kunstakademie

2010 – 2012 Kunstakademie Düsseldorf with Lucy McKenzie

2009 – 2010 Freie Universität Berlin, Philosophy

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2026 My Neighbor’s Flowers, Galerie Christine Mayer, Munich 2024 Word of Honor, M.LeBlanc, Chicago

2022 Cold Customs, Eastcontemporary, Milano Art-O-Rama, presented by Sans Titre, Marseille

Shoot the Moon, Mou Projects, Hongkong

2021 Rain or Shine, M.LeBlanc, Chicago At The Pawn Shop, Sans Titre, Paris

2019 Ganze Tage in den Bäumen, Kunstverein Heppenheim Desire/Delivery, June, Berlin

2018 Transit Papers – Aftermath of an Ideal’s Removal, Spazio Nea, Naples 2014 My Vain Plane, Kunsthaus Mettmann

2012 Gone Home, Lille Carl, Copenhagen

GRUPPENAUSSTELLUNGEN / GROUP SHOWS

2025 The Pamphlet Show II, Patient Info, Chicago

As if a line, Slip House, New York

IV, with Laura Bernstein, W.I.H.S.H. Projects, Chicago

2024 I’ll give it to someone special, Sans Titre, Paris Beginner’s Mind, Max Hetzler, Berlin

Landschaftsbilder, Bernd Kugler, Innsbruck

In sole ambulare, The Merode, Brussels

Pictures and Sundries, with Mari Eastman, Tusk, Chicago Moreover, Green Gallery, Milwaukee

Dass die Göttin…, Secci Gallery, Florence

91st Member Show, Arts Club of Chicago

2023 Homotopy Type Theory, Centralbanken, Oslo

Die Welt ist noch auf einen Abend mein, Galeria Ehrhardt Florez, Madrid

Barely Visible, Good Weather, North Little Rock, Arkansas EXPO Chicago, presented by M.LeBlanc, Chicago

2022 Moonlight Mile, Alan Koppel Gallery, Glencoe, IL

Mon Palais, choir, Sans Titre, Paris

The Armory Show, with Arnold J. Kemp, presented by M.LeBlanc, New York

May Selection, Platform by David Zwirner (online)

Sun Kissed, NEVÈ, Los Angeles

2021 Westbund Art & Design, presented by Mou Projects, Shanghai

Why do you give me no answer?, Slice, Uferstudios, Berlin

What’s Up London: L’univers d’un collectionneur, LVH, London

Make yourself at home, Sans Titre, Paris (online)

She Came To Stay, Andrea Festa Fine Art, Rome 2020 Groupshow, M.LeBlanc, Chicago

Material Art Fair, with Basile Ghosn, presented by Sans Titre, Mexico City

2019 Think in Pictures, curated by John Newsom & Matt Dillon, Amelchenko, New York

Chicago Invitational, presented by M.LeBlanc, Athletic Association, Chicago

2018 Ein Tun ohne Bild, Kunstverein Reutlingen, Reutlingen

I can bite the hand that feeds me and gently caress it too, Carbon12, Dubai

Ich liebe Dich geh weg, with Katharina Schilling, Angela Mewes, Berlin

A Solo Show on Planet Earth, with André Butzer & Josef Zekoff, Sunday-S, Copenhagen Clean Dishes, with Sarah Kürten, Christian Wieser & Fabian Ginsberg, Studio Nostitz, Berlin

2016 Topophobophilia, Gallery46, London

Adler Düsseldorf at Art Cologne, presented by Bruce Haines Mayfair, Cologne

2015 Quando il paesaggio è in ascolto, Capella di Incoronazione, Palermo

Local Color – Class of Elizabeth Peyton, Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf

Imagine, NewCastle Space, London

2013 Members of the Family, Kunstverein Emmerich, Emmerich

Painting of today, Artspace RheinMain, Offenbach

2011 Coco Collection, Atelier Max Benoit, St. Tyrosse de Vincent

Fremdgang International, ODG, Düsseldorf

2010 Arz and Friendz, Forgotten Bar, Galerie im Regierungsviertel, Berlin