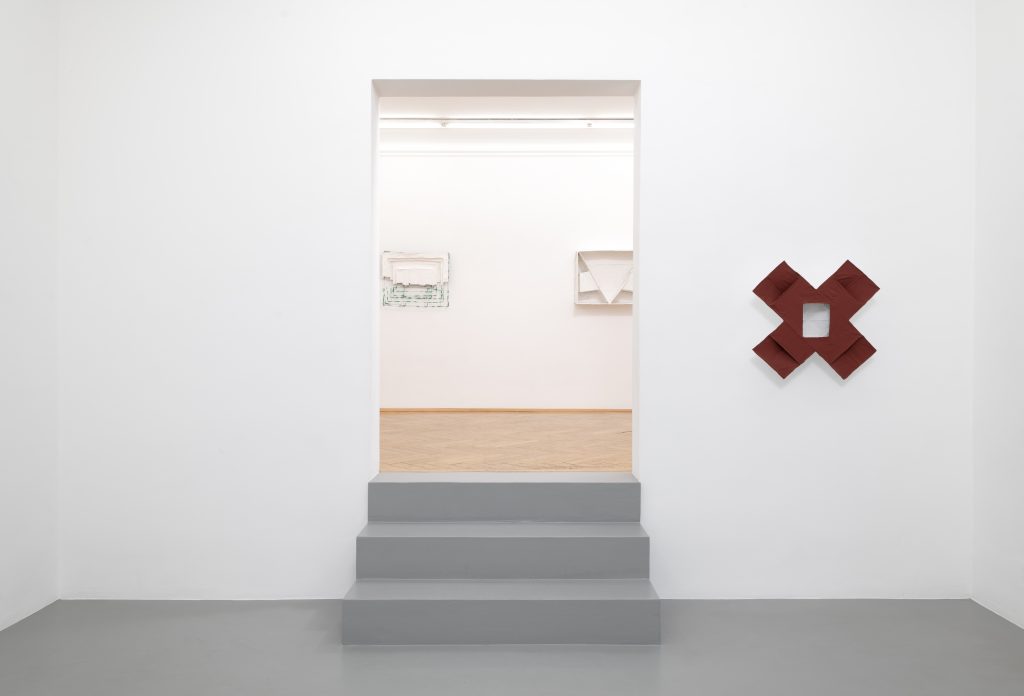

Installation view

Installation view

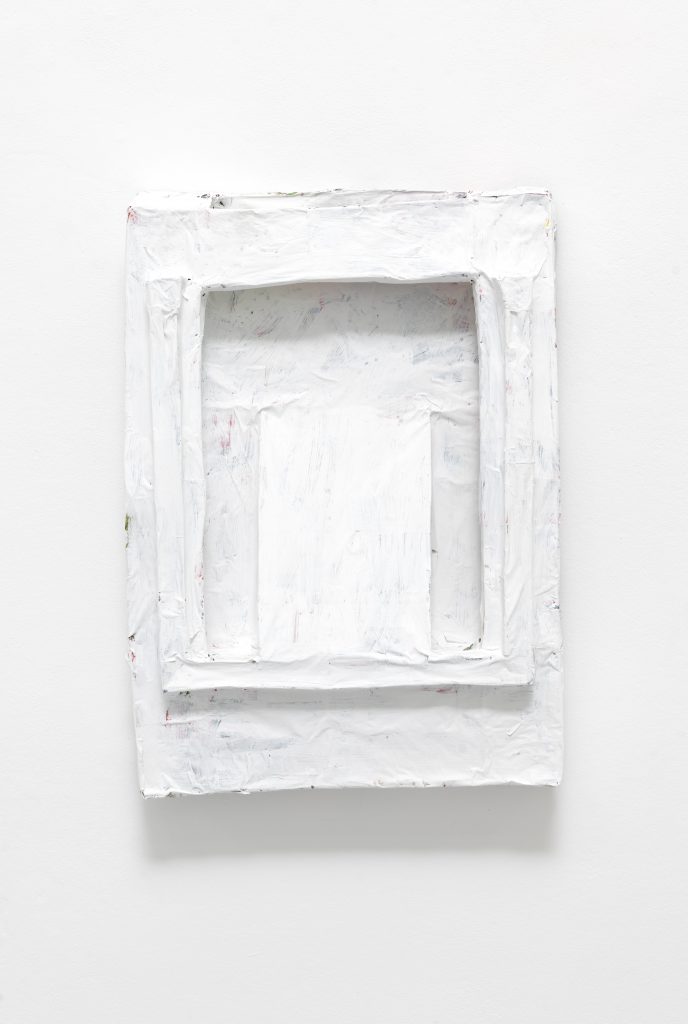

Das Bild, 2021, wire, paper and acrylic paint, 54,5 x 39,5 x 7,5 cm

Untitled, 2022, bronze, 33,5 x 27,5 x 9 cm

Installation view

Untitled, 2021, wire, paper and acrylic paint, 42 x 51 x 11,5 cm

Untitled, 2022, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 cm

Installation view

Kristall, 2021, wire, paper and acrylic paint, 63,5 x 67,5 x 13 cm

Installation view

Der Himmel, 2021, wire, paper and acrylic paint, 59,5 x 71 x 7,5 cm

Der Mensch, 2021, wire, paper and acrylic paint, 56,5 x 71 x 21, 5 cm

Installation view

Untitled, 2022, plastic and oil paint, 26,5 x 39 x 33,5 cm

Installation view

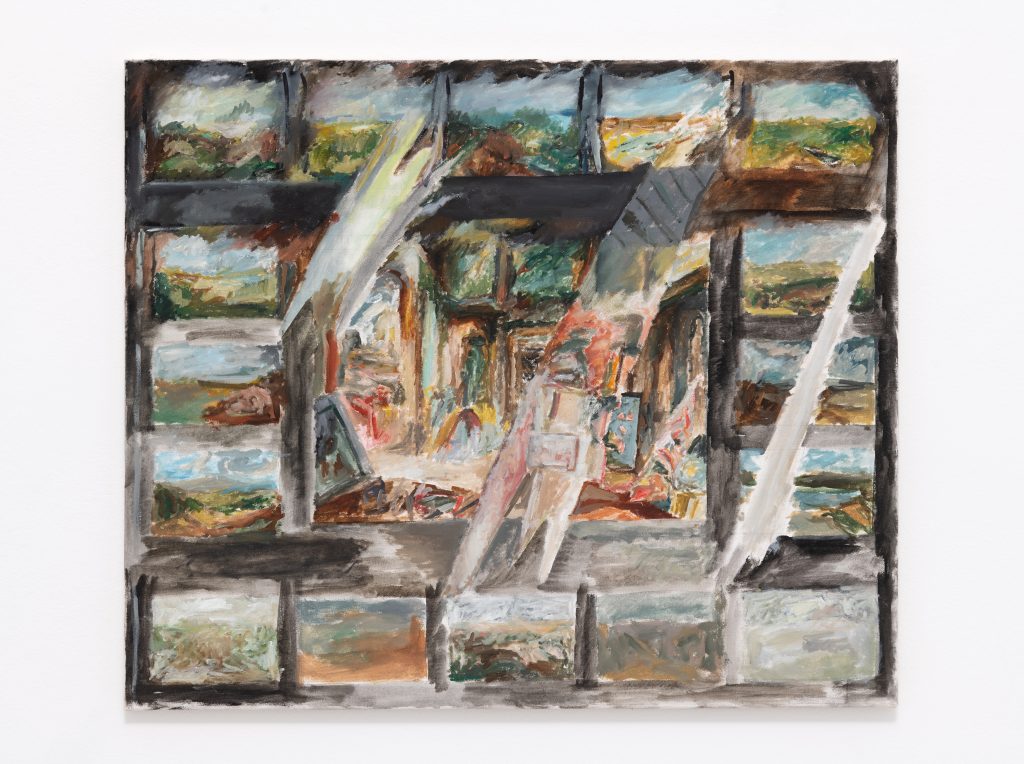

Untitled, 2022, oil on canvas, 74,5 x 88 cm

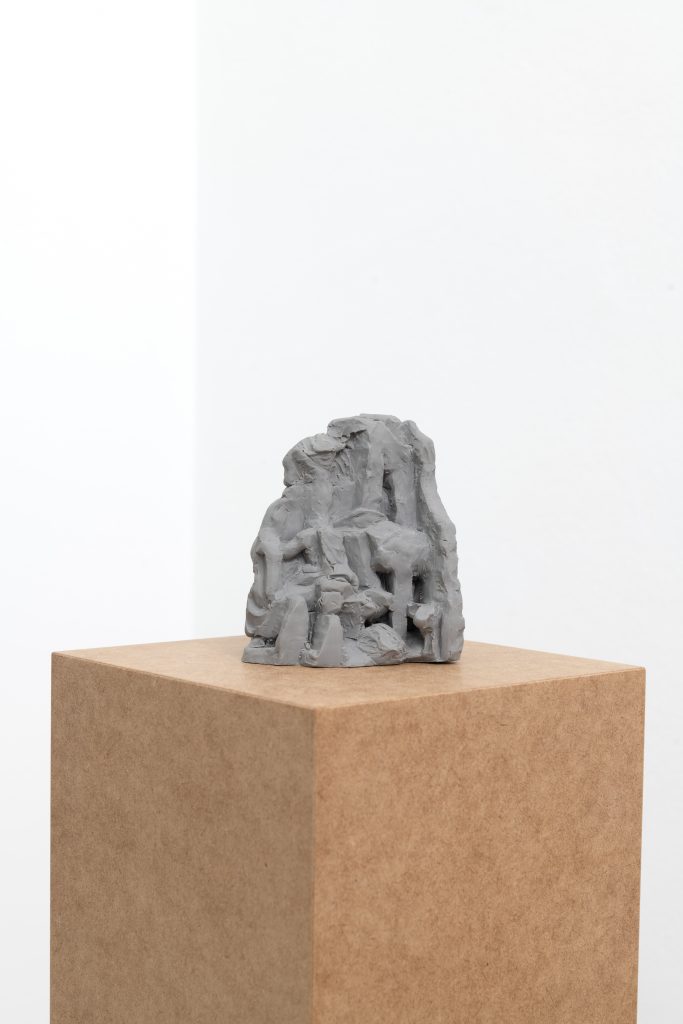

Untitled, 2023, bronze, 35,5 x 21,5 x 12,5 cm

Installation view

Untitled, 2022, plastic, 10,5 x 8,5 x 6 cm

Untitled, 2022, wire, paper and acrylic paint, 108 x 84 x 11 cm

Lasst uns nicht mit Armut anfangen, sondern mit Reichtum! Gewiss bringen reiche Künstlerinnen und Künstler nicht unbedingt besseres hervor. Und erst recht ist das Faktum, dass alles gesagt ist, ein Reichtum, der als solcher Vergangenheit ist und als Gegenwart Asche. Adorno weist auf den Spannungsverlust hin, den die Moderne erleidet und der auch die Reflexion irgendwann einholt.

In den Arbeiten von Emanuel Wadé bilden Fläche und Tiefe, Körper und Raum, Schweres und Leichtes keine postmoderne oder manieristische Diversität, die irgendwo nach der Geschichte stagniert, sondern erneut eine Spannung. Reliefs und Gemälde bieten nicht Ansichten, sondern Übersichten, etwa über eine ganze Landschaft, eine ganze Stadt, eine ganze Sammlung von Bildern. Aber diese Ganzheiten treten reich an Gegensätzen oder reichlich hybrid in Erscheinung. Relief und Bild, Zeitungspapier und Bronze gehen nicht um eines opaken Effekts willen, sondern auf transparente Art auseinander hervor. Und dass die Betrachtenden diesem Hervorgehen folgen können, macht sie zu Zeugen eines Hervortretens: Eine Stufenpyramide aus Kunststoff steigt über Ölfarben auf in den Himmel und lässt an den Turm in Babylon denken, der dem Bericht nach Anlass wurde für den Reichtum der Sprachen. Dieses Hervortreten bemerkt am ehesten, wer von sich selbst absieht oder nicht nur die eigene Sprache kennt. Karl Jaspers hat Kants Rede vom Genie als „die Natur in der Vernunft“ beschrieben.

Die Spannung, deren Verlust Adorno bemerkt, baut sich in den Werken Emanuel Wadés unbemerkt wieder auf. Die Tore und Durchblicke in seinen Gebilden bieten Passagen an in eine Welt aus Polaritäten, die die Betrachtenden endlich auch in sich selbst finden. Gewiss hat die Reflexion über Kunst nach Kant Polaritäten benannt wie apollinisch und dionysisch, optisch und haptisch, abstrakt und einfühlend, malerisch und zeichnerisch. Und jenseits der Bücher treten digital und analog kaum anders auf als konstruktiv und expressiv bei Adorno. Alle diese Gegensätze lassen sich auf Emanuel Wadés Werke beziehen. Aber die Polaritäten werden selbst umso ärmer, je mehr sie Buchstäbliches meinen und nicht mehr das Ganze. Sie treten damit als subjektive hervor und dem Kunstwerk selbst gegenüber. Der Gegenwart, die Emanuel Wadé zeigt, wird am ehesten die Einsicht gerecht, dass Wissenschaft immer nur subjektiv sein kann, Kunst dagegen immer nur objektiv. Schon in der Kritik der reinen Vernunft steht, dass 100 wirkliche Taler etwas ganz anderes sind als 100 mögliche Taler.

Berthold Reiß

Let’s not begin with poverty, but with wealth! Of course, rich artists don’t necessarily produce better work. And above all lies the fact that everything has been said, and thus wealth as such is the past while it is ash in the present. Adorno points to the loss of tension suffered by Modernity, which at some point also catches up with reflection.

In the works of Emanuel Wadé, surface and depth, body and space, heaviness and lightness, do not form a Postmodern or Mannerist diversity that stagnates somewhere after history, but rather a renewed tension. Reliefs and paintings do not offer points of view, but overviews; for example of an entire landscape, an entire city, or an entire collection of images. Yet, these totalities are rich in contrast or appear richly hybrid. Relief and image, newsprint and bronze do not emerge for the sake of creating an opaque effect but they do so in a transparent way. And the fact that the viewer can follow this process makes them witness to the emerging work: a step pyramid made of plastic rises into the sky over oil paints and is reminiscent of the Tower of Bable, which is assumed to be responsible for the richness of languages. This emergence is most likely to be noticed by those who ignore themselves or those who do not only know their own language. Karl Jaspers described Kant’s notion of genius as “nature in reason”.

The loss of tension Adorno referred to is secretly rebuilt in the works of Emanuel Wadé. The gates and perspectives in his works offer passages into a world of polarities, which viewers will eventually also find within themselves. Indeed, reflections on art after Kant named polarities, such as Apollonian and Dionysian, optical and tactile, abstract and empathetic, painterly and graphic. And beyond the books, the digital and analog spheres hardly differ from Adorno’s notions of the constructive and the expressive. All of these contrasts can be traced to Emanuel Wadé’s work. Yet, the polarities themselves become poorer the more they venture into the literal realm rather than the whole. They thus emerge as subjective and opposed to the work of art itself. The insight that science can only ever be subjective, while art, on the other hand, can only ever be objective, does justice to the present as shown by Emanuel Wadé. The Critique of Pure Reason already mentions that 100 actual thalers are something completely different to 100 potential thalers.

Berthold Reiß

Translated by Melanie Waha