Alles Leben einschließlich Flugzeuge

Eine Arbeit, die ohne Wenn und Aber entsteht, wird gern vergangen genannt und zugleich erwartet. 1846 fragt Charles Baudelaire: “Was ist Romantik?” und findet die Antwort: “Wer Romantik sagt, sagt moderne Kunst.” Diese Kunst sei “Intimität, Geistigkeit, Farbe, Streben nach dem Unendlichen, ausgedrückt durch alle Mittel, die die Künste enthalten.”

Emanuel Wadé scheint diese Prophezeiung einer Moderne zu erfüllen, indem er von sich ausgeht und unerschöpflich Farbiges und Raffiniertes hervorbringt. Auch in der Wiederholung gerät die Imagination nie in die Gleise der Konstruktion, die Überraschung versandet nie im Spektakel. Die Wiederholung wirkt nicht entleerend, sondern vertiefend, wenn die Ideen nicht neu, sondern einfach sein wollen. Die Romantik und die Moderne, die Geistigkeit und die Farbe, die Intimität und die Kunst, von denen Baudelaire spricht, stellen sich bei Emanuel Wadé nicht als Gegensätze dar, sondern wie natürliche Polaritäten. In seinen Reliefs wirken die Farben nur auf andere Art plastisch. In seinen Skulpturen wirken die aus Draht gebogenen Sphären nicht fremder als der Globus, den wir uns ohne Raumschiff auch nur vorstellen können. Der Titel “Alles Leben einschließlich Flugzeuge” ist vor drei Tagen in einem Café entstanden. Er weist darauf hin, dass Emanuel Wadé sogar diese Fahrzeuge aufnimmt in ein Ganzes, das uns keinen Anblick, aber dafür einen Aufenthalt bietet.

In einer Tafel, die Emanuel Wadé einmal für sich formuliert hat, stellt er Schiff und Muster, Figur und Landschaft nebeneinander. Schiff und Figur sind beide eines, Muster und Landschaft dagegen vieles. Giorgio Agamben hat bemerkt, dass es in der Antike nicht um Subjekt und Objekt gegangen sei, sondern um eines und vieles. Natürlich wiederholt Emanuel Wadé keine bekannte Antike. Er entdeckt auch keine unbekannte Antike, die den Farben nach in Nordafrika läge. Dennoch zeigt er einen Sinn, einen Zusammenhang, der nur darum verborgen ist, weil wir ihn dauernd bewohnen.

Berthold Reiß

Alles Leben einschließlich Flugzeuge

[All Life including Airplanes]

A work of art that is created without ifs and buts is often perceived as passé and yet at the same time expected. In 1846, Charles Baudelaire asked: “What is Romanticism?” To this question he found the following answer: “To say the word Romanticism is to say modern art – that is, intimacy, spirituality, colour, aspiration towards the infinite, expressed by every means available to the arts.”

Emanuel Wadé seems to fulfil this prophecy of modernity in that he sets out from within himself and continually creates something colourful and sophisticated. Even in repetition, his imagination is never caught in the tracks of construction, and surprise never disappears into spectacle. Repetition does not have the effect of emptying, but of deepening; ideas do not necessarily have to be always new, but instead are allowed to simply exist. In Emanuel Wadé’s work, romanticism and modernism, spirituality and colour, intimacy and art – which Baudelaire speaks of – do not appear as opposites, but as natural polarities. In his reliefs, colours take on a different kind of plasticity. The spheres made of wire in his sculptures seem no stranger than planet Earth which we can only attempt to imagine in its entirety. The title “All Life including Airplanes” was conceived three days ago in a café: it refers to the fact that Emanuel Wadé includes even such objects as airplanes into a single entity which in turn provides us with a place of refuge and encounter, instead of a mere vision.

In a panel that Emanuel Wadé once devised for himself, he juxtaposes ship and pattern, figure and landscape. Ship and figure are one thing, while pattern and landscape represent many things. Giorgio Agamben noted that antiquity was not concerned with subject and object, but rather with singularity and plurality. Of course, Emanuel Wadé does not reiterate the ancient world as we know it. Nor does he reveal an unfamiliar antiquity, which, according to his colours, would be located in North Africa. What he does instead is to offer us a sense of meaning and connectivity which remains hidden only because we constantly live within it.

Berthold Reiß translated by Jennifer Leetsch

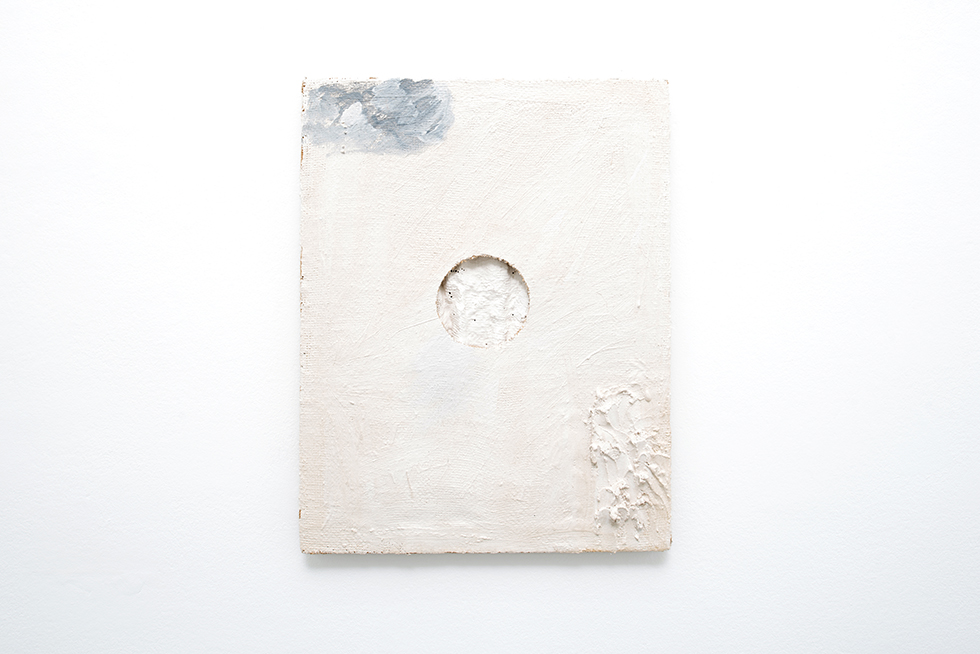

78 x 110 x 8 cm

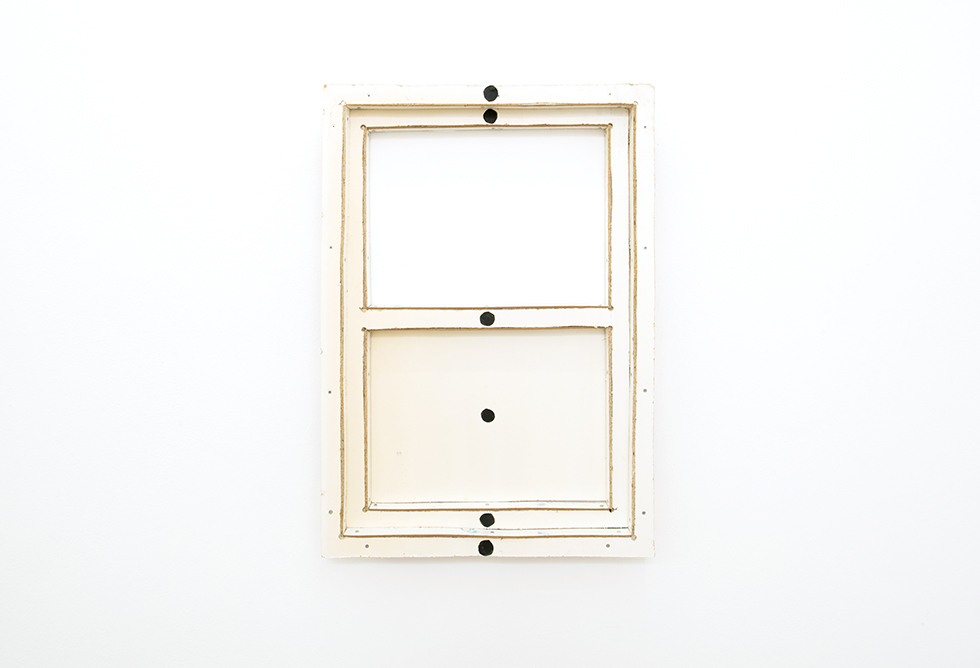

78,5 x 111 x 8 cm

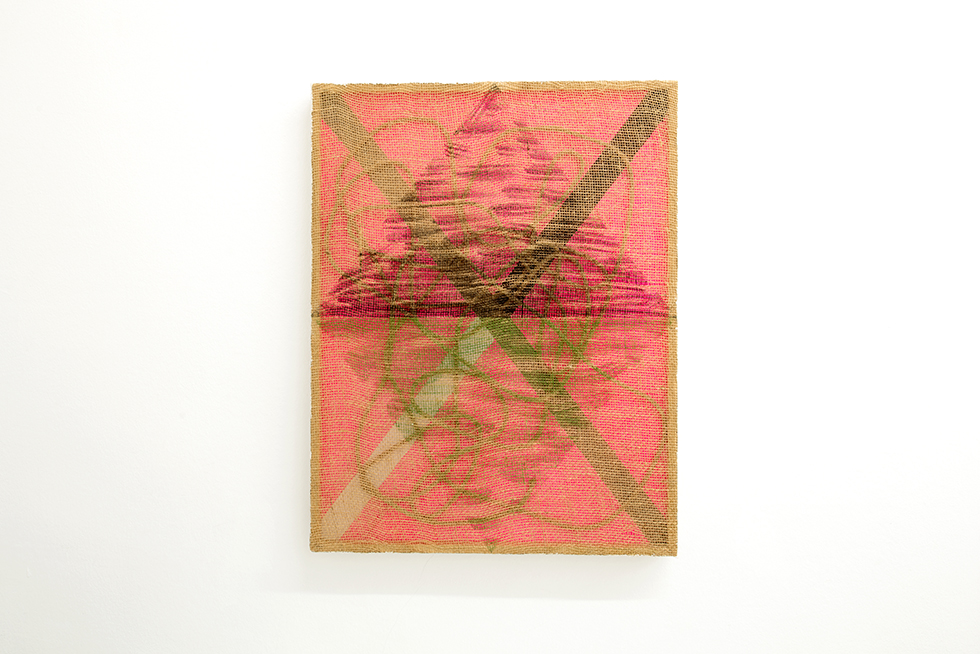

68,5 x 53 x 8 cm

68,5 x 53 x 8 cm

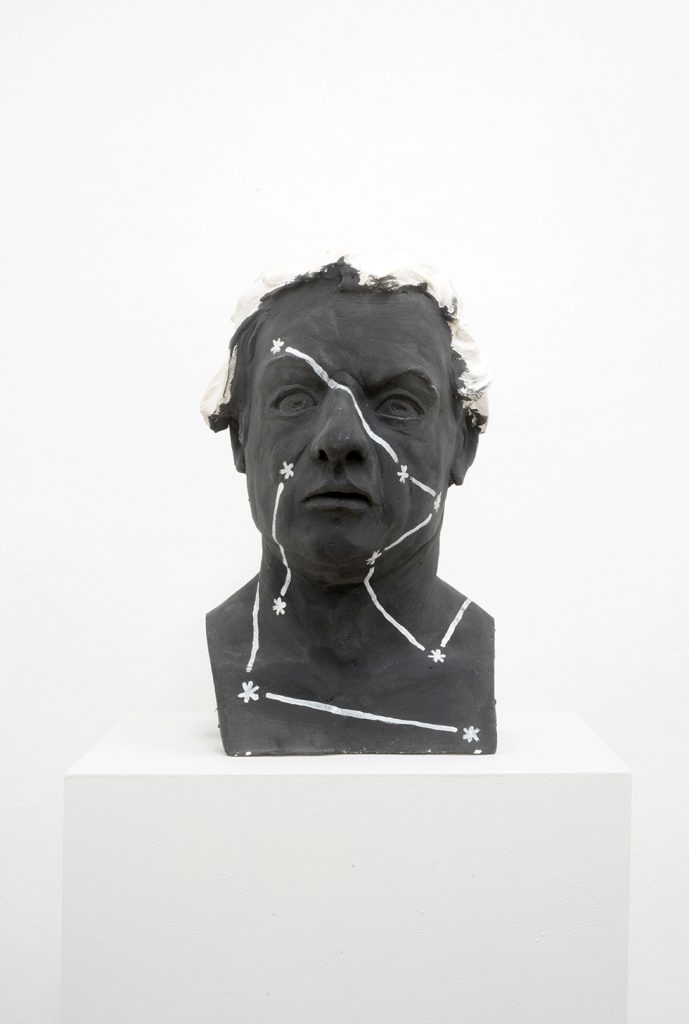

39 x 38 x 26 cm

59 x 42 x 11 cm

72,5 x 51 x 6,5 cm

42 x 35 x 25 cm

78 x 110 x 8 cm

58 x 108 x 10 cm

67 x 33 x 33 cm

46 x 31 cm

53,5 x 54,5 cm

68 x 53 x 5,5 cm

58 x 64 cm

58 x 64 cm

175 x 85,5 cm

34 x 20 x 20 cm