Installation view

Installation view

Untitled, 2016, synthetic fibre, two scenes platforms

Blanket: 250 x 250 cm, platforms: 60 x 200 x 200 cm

Installation view

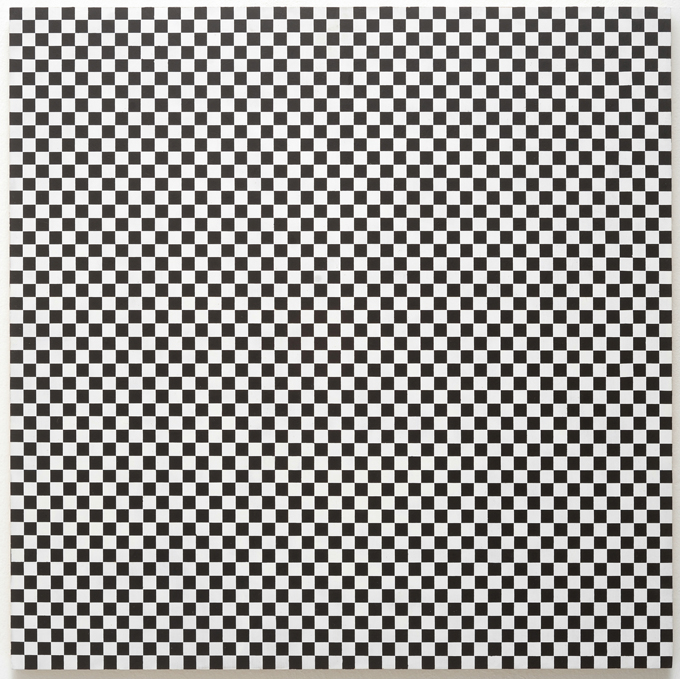

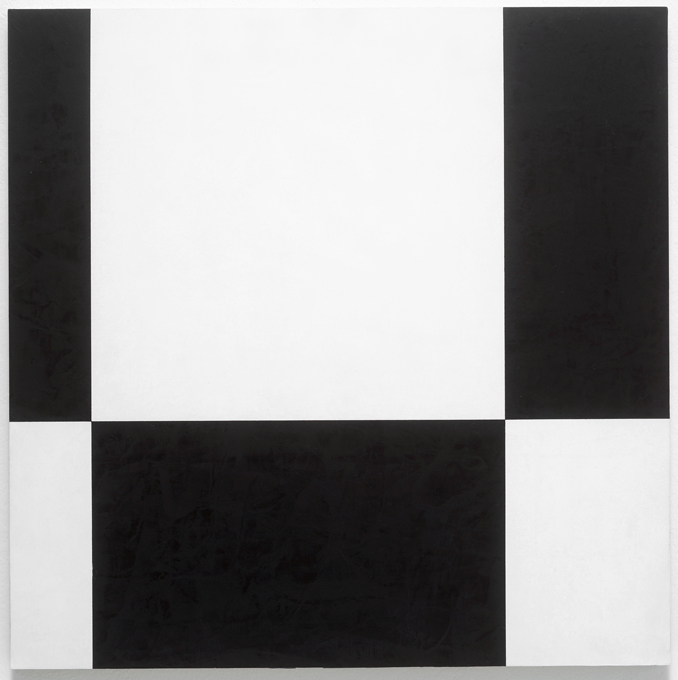

Untitled, 2005, acrylic on MDF

50 x 50 cm

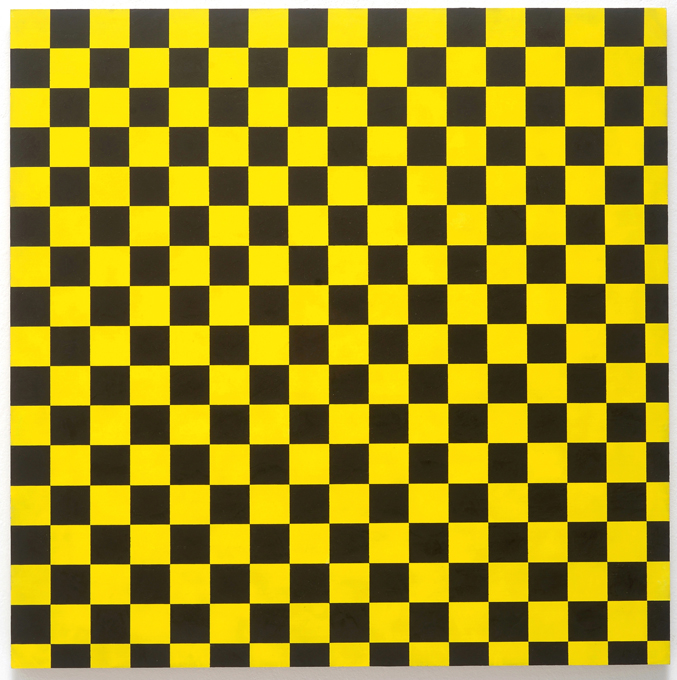

Untitled, 2005, acrylic on MDF

50 x 50 cm

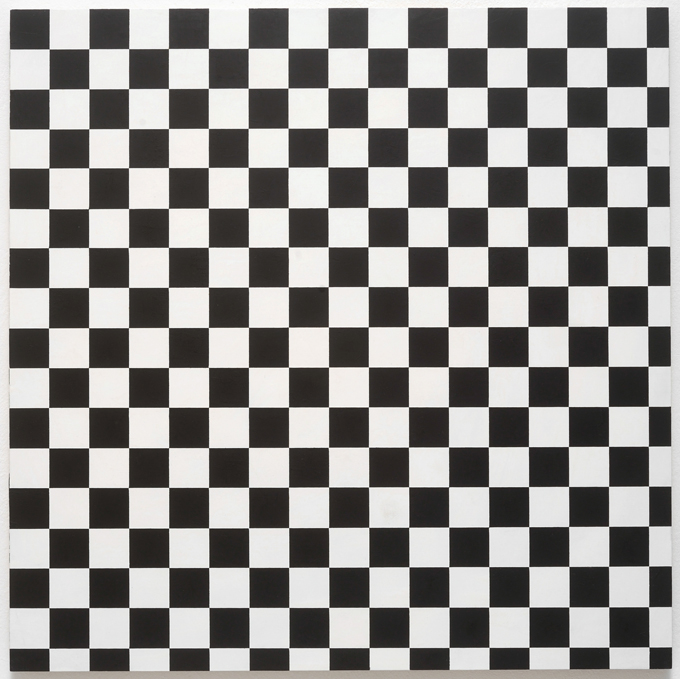

Untitled, 2005, acrylic on MDF

50 x 50 cm

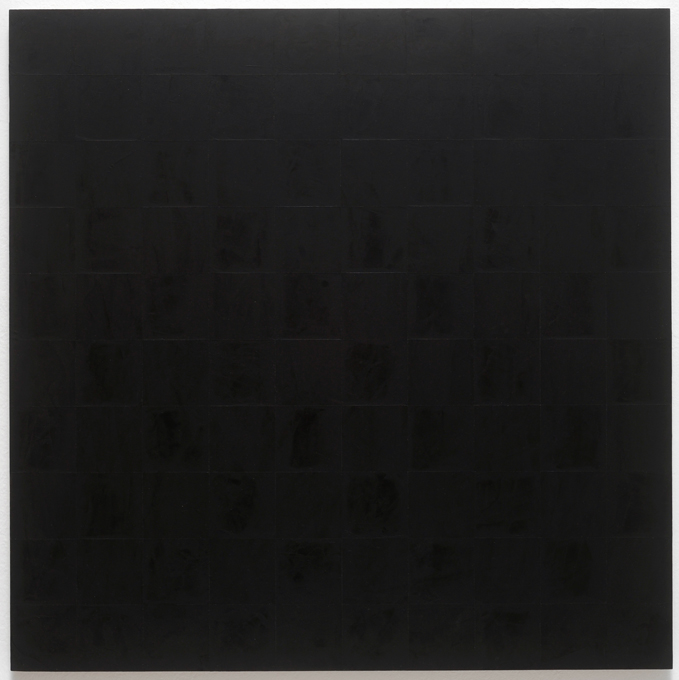

Untitled, 2005, acrylic on MDF

50 x 50 cm

Untitled, 2005, acrylic on MDF

50 x 50 cm

Untitled, 2005, acrylic on MDF

50 x 50 cm

Untitled, 2005, acrylic on MDF

50 x 50 cm

In Anlehnung an seine erst kürzlich beendete Ausstellung wood painting in der Malmö Konsthall (Schweden), rückt in der aktuellen Ausstellung von Heimo Zobernig in der Galerie Christine Mayer das Schachbrett in den Mittelpunkt. Trämålning (Wood Painting) war einem Theaterstück von Ingmar Bergman entlehnt, ursprünglich wurde es als Übung für Schauspielschüler am Malmöer Stadttheater verfasst und in abgewandelter Form 1957 unter dem deutschen Titel Das Siebente Siegel verfilmt. Handlungstreibendes Motiv des im 14. Jahrhundert angelegten Stücks ist der Pakt eines sinnsuchenden Kreuzritters mit dem Tod, um den Aufschub seines Sterbens zu erreichen – die ausgehandelte Frist umfasst die Dauer eines Schachspiels. In Malmö war Heimo Zobernig auch auf die vorangegangene Ausstellung von Joan Jonas eingegangen und integrierte die umgelegten temporären Stellwände.Wie der durchgestrichene Schriftzug wood painting schon impliziert, ist das zentrale Element der Ausstellung im ersten Raum der Galerie eben kein „wood painting“, sondern ein gedoppeltes Scherenpodest auf dessen Holzplatten eine Decke in schwarz-weißem Schachbrettmuster aufgelegt ist. Die stoffliche und haptische Qualität des Textils sowie seine Drapierung mit Wölbungen und Höhlungen stört das puristische System des auf orthogonalen Koordinaten beruhenden geometrischen Musters auf der Oberfläche. Mit subversiver Leichtigkeit wird hier die Vorherrschaft des mathematisch Rationalen zurück ins Sinnlich-Malerische überführt. Das Objekt provoziert geradezu, als Sitz- oder Lagerplatz genutzt zu werden – wodurch der Betrachter spielerisch ironisch und ganz wörtlich als Figur wieder hinein in den Bildgrund versetzt wird. Der abstrakte Minimalismus des 20. Jahrhunderts hatte der Narration und Figuration seine Absage erteilt. Mit dem Geniestreich der Entgrenzung wird hier der malerei-theoretische Verlust der Figur und des gestischen Moments aufgehoben und das ursprüngliche Prinzip wieder hergestellt. Das Schachbrett ist eine wiederkehrende Konstante im Werk von Heimo Zobernig mit der er den Diskurs über den Formalismus in unterschiedlichen Materialien und Verfahrensweisen immer wieder aktualisiert. Eine Referenz, auf die er beispielsweise 2015 bei David Pestorius in Brisbane verwies, sind die im 18. Jahrhundert typischen schwarz-weißen Fußböden als Spiegel des rationalistischen Geistes der Aufklärung. In Brisbane expandierte das Schachbrettmuster auf die Gesamtfläche der Wände und neutralisierte sie so als Um- und Begrenzungslinie der Architektur.

In der 2005 entstandene Serie aus sieben abstrakten MDF-Bildern, die im zweiten Raum präsentiert wird, ist Holz tatsächlich der Bildträger. Als Motiv dominiert das quadrierte Raster als ein sich in Variation wiederholendes Vokabular von Schwarz und Weiß. Nur bei zwei Exemplaren gibt es eine Auflockerung durch Gelb bzw. Rot. Ein schwarz-weißes Streifenbild trotzt dem quadratischen Formalismus. Über das demokratisch codierte Material MDF wird bereits der Malgrund dem minimalistischen Prinzip zugeführt. Die Verfahrensweise der Abklebe- und Spachteltechnik führt diesen Ansatz weiter und zeigt sich zudem, gemeinsam mit der formalen und farblichen Reduktion, als Erbe des Neoplastizismus Piet Mondrians. Als konkretes Zitat ließe sich das Gitterbild New York City 1 von 1941 anführen, bei dem Mondrian anstelle der Farbe zum Klebeband übergeht und eine neue Stufe der rhythmischen Harmonie im Bild erreicht, kunsthistorisch als Konsequenz seines Umzugs von Paris in die amerikanische Metropole gewertet. Die Arbeit blieb durch Mondrians Tod unvollendet und öffnet damit den Raum für spekulatives Weiterdenken. Im monochrom-schwarzen MDF-Bild mit seiner deutlichen Anlehnung an die Konstruktivisten zeigt sich das Schachbrett in feinsten Farbnuancen von Mattschwarz. Das rot-weiße Bild, das den Abschluss der Serie bildet, erinnert an Blinky Palermos Flipper-Bilder. Entgegen dem ersten Eindruck der klaren reduzierten Formensprache schafft Heimo Zobernig hier vieldeutige Situationen, indem er zum einen verschiedenste historische Vorbilder aufruft und zum anderen das Schachbrett als Bildprinzip von neuem in Bewegung setzt.

Connecting back to his recent display wood painting in the Konsthall Malmö (Sweden), the current exhibition by Heimo Zobernig in Galerie Christine Mayer has at its heart a chess board. Trämålning (Wood Painting) has its origin in a play by Ingmar Bergman – it was initially created as an exercise for drama students at the city theatre Malmö and was adapted in slightly modified form into a film with the title The Seventh Seal in 1957. The play is set in the 14th century and the driving element of the plot is a crusader who forges a pact with the devil to hold off death; he manages to negotiate a time span which lasts exactly one game of chess. In Malmö, Heimo Zobernig also referenced the earlier exhibition by Joan Jonas by integrating its temporarily movable walls.

As the crossed-out wood painting already implies, the exhibition’s central element in the first room is not a “wood painting”but a doubled wooden platform which carries a throw with a black-and-white chequerboard pattern. The textile and haptic quality of the fabric and its arrangement in folds and bulges disrupts the purist, clean system of the geographical surface, which is based on orthogonal coordinates. With subversive lightness, the mathematically rational is transformed into a sensual aesthetic. The object almost provokes sitting or lying down – the spectator is literally inserted back into the artwork by way of playful irony. Abstract minimalism of the 20th century had rejected narration and figuration. Here, the loss of them is counteracted to restore the gestural, physical moment in complexly playing with these border crossings. The chess board is a recurrent theme in Heimo Zobernig’s work with which he constantly renews the discourses of formalism by employing various materials and procedures. At David Pestorius in Brisbane in 2015 for example he pointed to the 18th century’s preference for black-and-white chequerboard floor patterns – they reflected the rational impetus of the Enlightenment. In his exhibition in Brisbane, Zobernig expanded this pattern over the walls and thus neutralized their function as architectural border guards.

In the series of seven abstract MDF pictures which were created in 2005 and can be found in the second room, wood actually acts as carrier. The main motive here is the squared grid which repeats itself within the vocabulary of black and white patterns. Only two examples loosen up this arrangement via the colours yellow and red respectively. One black-and-white picture defies the squares with its stripes. Via the democratically coded material of MDF, the paintings’ foundations carry the minimalistic principle so characteristic for Zobernig’s work. This approach is further pursued by the techniques of trowelling, scaffolding and gluing – together with the reduction on the formal level and in terms of colour, this hints at Piet Mondrian’s neoplasticism. One concrete reference point is Mondrian’s grid painting titled New York City 1 from 1941. Here, he substitutes colour with tape to reach a new level of rhythmic harmony. This has often been interpreted as a consequence of his move from Paris to the American metropolis. Mondrian’s death left he work incomplete and thus opens up a space to speculatively continue his thought processes. The monochrome-black MDF artwork clearly references the constructivists and displays an elegant pattern of tarnished blacks. The red-and-white painting which forms the series’ conclusion, recalls Blinky Palermo’s pinball paintings. Contradicting the first impression of a clear and reduced use of forms, Heimo Zobernig has created multi-faceted and complex situations in both invoking historical role models and in setting in motion the chess board as an elementary principle of his art.

By Agnes Stillger, translated by Jennifer Leetsch