Installation view

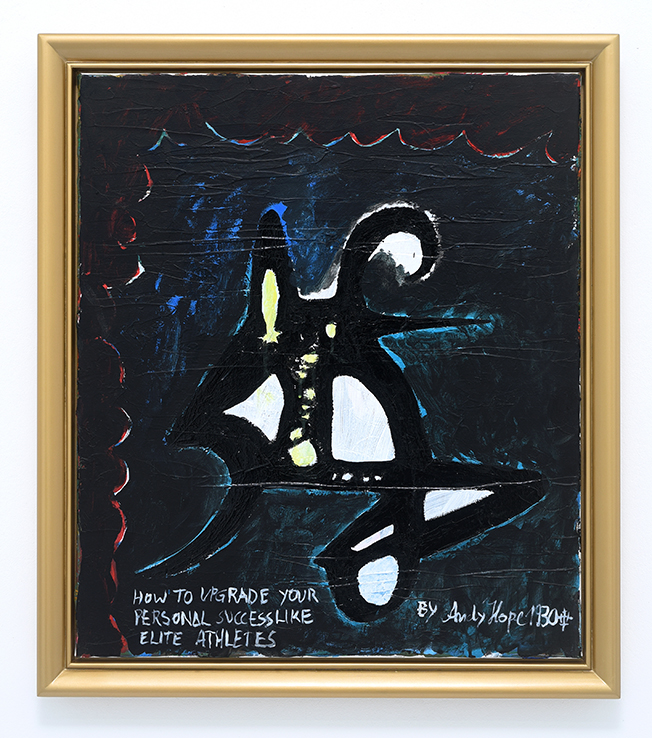

How to Upgrade Your Personal Success Like Elite Athletes, 2017, acrylic and lacquer on canvas

70 x 60 cm

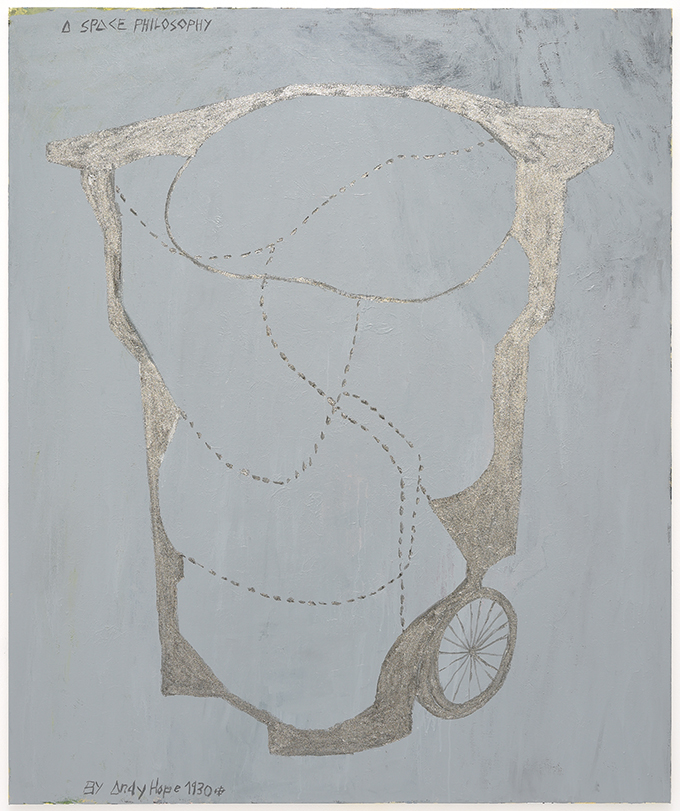

A Space Philosophy IV, 2018, acrylic, lacquer and glitter on canvas

180 x 150 cm

Installation view

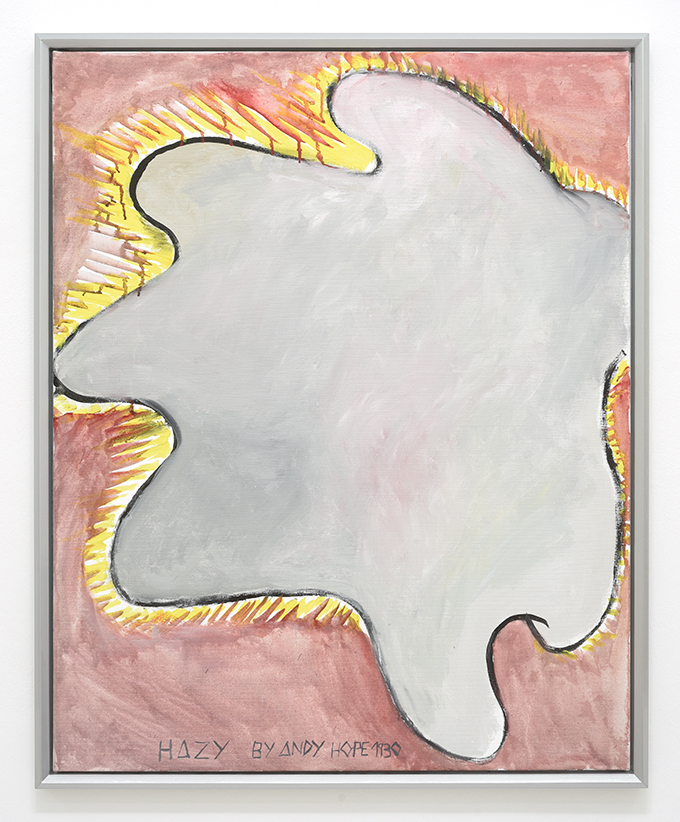

Hazy, 2018, acrylic and lacquer on canvas

102 x 80 cm

Blob, 2018, acrylic and lacquer on canvas

80 x 70 cm

Mass, 2018, acrylic and lacquer on canvas

102 x 80 cm

Raw, 2018, acrylic and lacquer on canvas

80 x 70 cm

Installation view

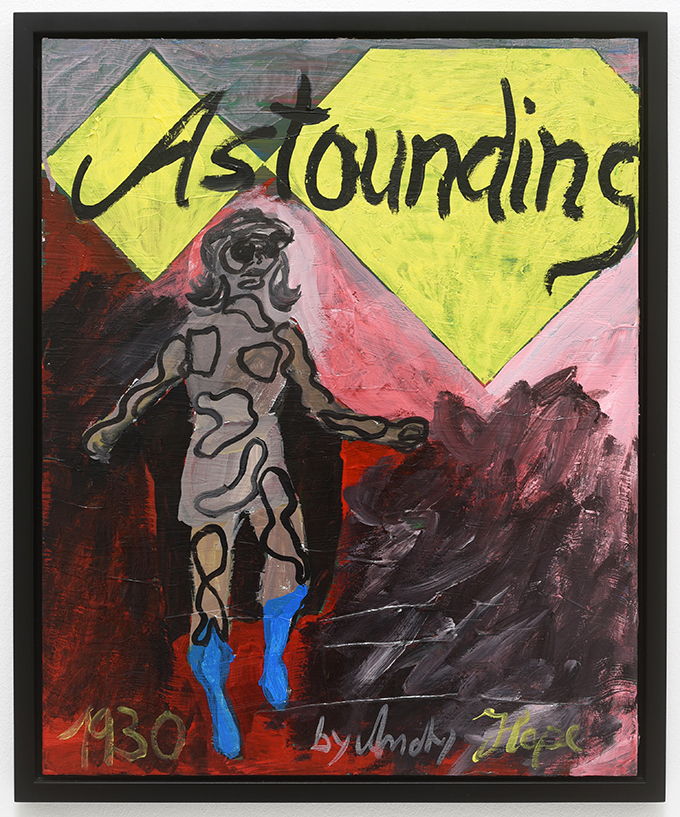

Astounding, 2010, acrylic on board

52 x 43 cm

A Space Philosophy, 2018, digital colour print, edition 1/10 + 2 AP

118,9 x 84,1 cm

Installation view

A Space Philosophy: Plozloz and Beyond I, 2018, watercolour, ink, pencil and collage on paper

29,5 x 21 cm

A Space Philosophy: Plozloz and Beyond II, 2018, watercolour, ink and pencil on paper

29,5 x 21 cm

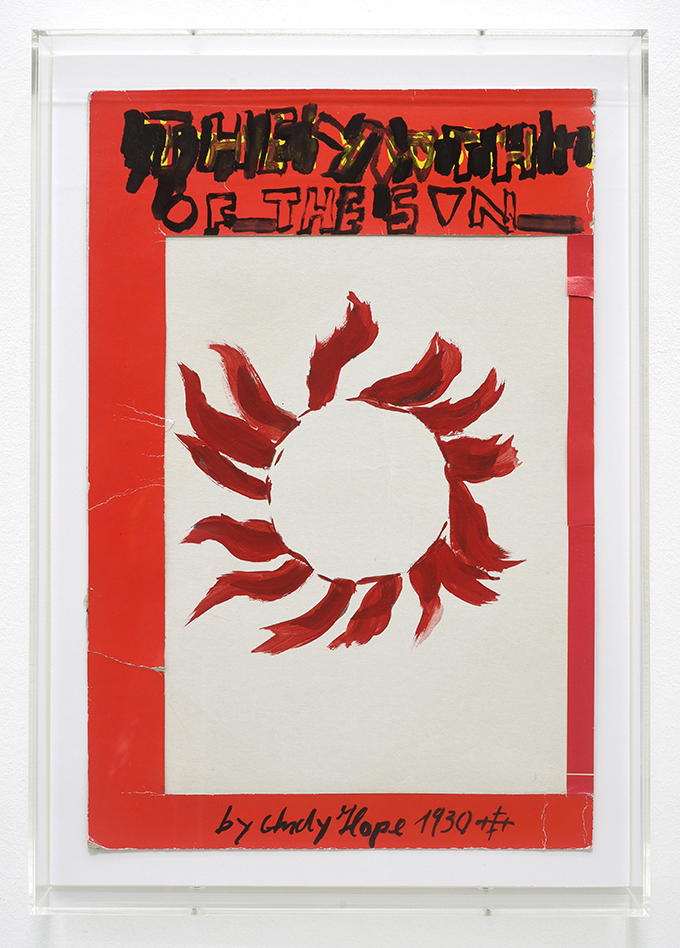

The Youth of the Sun, 2010, acrylic on cardboard

40 x 27,1 cm

Die beiden Bilderserien in der Ausstellung A Space Philosophy: Plozloz And Beyond von Andy Hope 1930 nähern sich der Malerei durch Untersuchungen des Molekularen und des Kosmologischen aus einer futuristischen Perspektive.

Die zentrale und größte Arbeit der Ausstellung, A Space Philosophy IV (2018), ist Teil einer aktuellen Serie von „Mülltonnenbildern“ (sie nahm ihren Anfang in den vorhergehenden Ausstellungen bei Lomex, New York und Rat Hole Gallery, Tokio), auf denen kosmologische Elemente und Symbole zu sehen sind, die in der Umrisslinie einer Mülltonne enthalten sind. In diesem Bild nun werden die elliptischen Galaxienhaufen wie Müllsäcke in den Container gestopft, die sich aus ihren immer größer werdenden, kosmischen Leerräumen aufblähen. Neben der eindeutigen Konnotation eines „trashigen“ Kunstwerks – verdoppelt durch die Verwendung von silbernem Glitterlack, der billigen Version von Make-up – bezieht es sich auch auf das Medium der Malerei selbst; nämlich auf die Frage, wie man „Raum“ aufteilt, wie man eine Oberfläche partitioniert.

Eine der ambitioniertesten Herausforderungen der Menschheit (oder deren Fluchtweg) ist heute die „Kolonisierung“ des Weltraums, dessen Inbesitznahme durch das Ziehen von Trennlinien bis ans Ende der Technologiegrenzen – ein äußerst fragwürdiges Unterfangen, das nicht nur eine kolonialistische Mythologie in der Sprache fortsetzt, sondern auch zu tatsächlicher Ausbeutung und Vertreibung auf der Erde führen könnte, zum Beispiel durch die Verlagerung von Mitteln aus der Sozialfürsorge (auf der Erde) in die Kriegsführung (im Weltraum). Die Aquarellcollage der Einladungskarte könnte ebenfalls auf dieses zukünftige Szenario anspielen – die Kuh auf einem anderen Planeten, eine Sauerstoffflasche auf dem Rücken tragend, die Kontinente der Erde als Flecken auf ihrem Körper wie eine bunte Erinnerung an die zurückgelassene Heimat: ein essentieller Bestandteil für die Errichtung einer dauerhaften landwirtschaftlichen Siedlung im Hyperspace.

Die zweite Serie von Bildern besteht bisher aus vier Variationen einer amorphen Form mit den Titeln Raw, Hazy, Mass und Blob (alle 2018), die in Farbe, Form und Stil variieren. Diese Formen oder Noch-Nicht-Formen, die sich fast über die gesamte Oberfläche der Leinwand ausdehnen – auf zwei Bildern sogar darüber hinaus – scheinen in einem Zustand der Metamorphose zu sein, als Körper, die sich der Abstraktion annähern.

Durch alle Zeiten hinweg scheint die Vorstellung einer Form ohne Zweck die Menschen zutiefst verstört zu haben, da sie als seelenlos, als grundlos wahrgenommen wurde, als etwas, mit dem man nicht räsonieren kann. Neoplatoniker glaubten, dass die Form von einer Idee bestimmt wird, und so lange Materie formbar ist, wäre sie neutral, aber wenn Form und Idee nicht erkennbar sind, wäre sie böse. In dem Science-Fiction-Klassiker The Blob (1958) wird ein stetig wachsender und seine Form verändernder gallertartiger Blob „immer größer und größer“ (Steve McQueen), während er Menschen frisst.

Wenn wir jedoch einen biohistorischen Ausflug zurück zu unseren Ururahnen im Präkambrium machen – zum Beispiel zu den Klümpchen Schleim in einem warmen Moor, die ein von der Sehnsucht nach umgekehrter Evolution ergriffener Gottfried Benn heraufbeschwor – stehen die Blobs am Anfang allen Lebens. Und sie bleiben am anpassungsfähigsten, genau wie ein Blobfisch, der Tausende von Metern unter Wasser lebt, seine Gestalt zusammengedrückt und sich ständig unter dem Gewicht des Wassers neu konfigurierend. Das Produktdesign der Zukunft wird ähnlich anpassungsfähig sein, es wird weit über abgerundete Kanten hinausgehen und stattdessen formverändernde, umschließende, biegsame Formen hervorbringen.

In der Bilderserie von Andy Hope 1930 scheinen diese Blobs auf das Bild geworfen worden zu sein, sie scheinen an der Oberfläche zu kleben, die Leinwand zu verschlingen, sie mit ihrer Nichtform zu negieren. Dabei rufen sie verschiedenste Assoziationen hervor: von Hokusais Großer Welle von Kanagawa über eine Sprechblase in einem Comicstrip von Lichtenstein bis hin zu einem Spritzer Dreck.

Man kann in eine Mülltonne schauen, um Geschichte zu sehen, diese Geschichte zerfällt jedoch unweigerlich in Blobs von molekularer Materie, die der Anfang und das Ende von allem sind.

Manuel Gnam

The two groups of paintings in the exhibition A Space Philosophy: Plozloz And Beyond by Andy Hope 1930 approach painting as probings into the molecular and the cosmological from a futurist perspective.

The central and largest work in the show, A Space Philosophy IV (2018), is part of a recent series of “garbage can paintings” (shown in previous exhibitions at Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo and Lomex, New York) in which we see cosmological units and symbols contained within the outline of a garbage can. Here, the elliptical clusters of galaxies are stuffed into the container like bin bags, each in itself ballooning out from their ever expanding, star-filled voids inside. Besides the clear connotation of a “trashy” artwork – doubled up by the use of silver glitter paint, the cheap version of makeup – it also refers to the medium of painting itself; namely to the question of how to distribute “space”, how to partition the surface plane.

One of humanity’s most aspirational challenges (or escape routes) today is the “colonization” of space, the drawing of lines of ownership through to whatever frontier is within our technology’s perimeters – a highly questionable endeavor that does not just continue a colonialist mythology in language, but might also cause actual exploitation and displacement on earth, for example through shifting funds from welfare (on earth) to warfare (in space). The watercolor collage of the invitation card could also allude to this future scenario – the cow on another planet carrying an oxygen bottle, the earth’s continents on its body like a colorful memory of home, as an essential part of setting up a sustainable agricultural settlement in hyper space.

The second series of paintings so far consists of four variations on an amorphous form called Raw, Hazy, Mass and Blob (all 2018) differing in color, shape and style. Stretching over nearly the whole surface of the canvas – on two paintings even going beyond it – these forms or not-yet-forms seem to be in a state of metamorphosis, as bodies approximating abstraction.

Throughout time, the idea of a form without meaning seems to have deeply unsettled people as it is perceived as having no soul, no reason, nothing to argue with. Neoplatonists believed that form is governed by an idea, so as long as matter is capable of form it is neutral, but if form and idea are indiscernible it is evil. In the science-fiction classic The Blob (1958) a growing shapeshifting blob of jelly “keeps getting bigger and bigger” (Steve McQueen) as it eats people.

However, taking a bio-historical trip back to our ur-ancestors in the Precambrian – for instance the globs of slime in a warming moor that Gottfried Benn called for, stricken by a yearning for reverse evolution – the blobs are at the beginning of all life. And they remain the most adaptable, just like a blobfish living thousands of feet underwater, its gestalt squashed and constantly reconfiguring under the weight of the water. Product design of the future will be similarly adaptable, it will go way beyond curved edges and instead produce shapeshifting, enveloping, pliable forms.

In Andy Hope 1930’s painting series, it seems these blobs were thrown at the picture, sticking to the surface, devouring the canvas, negating it with their non-form, whilst still evoking associations from Hokusai’s Great Wave of Kanagawa to a speech bubble in a Lichtenstein comic strip to a speckle of dirt.

As you can look into a bin to view history, this history inevitably decomposes into blobs of molecular matter which are the beginning and end of everything.

Manuel Gnam