Installation view

Play structure, 2021

Oil on canvas

18,5 x 23,5 cm

Installation view

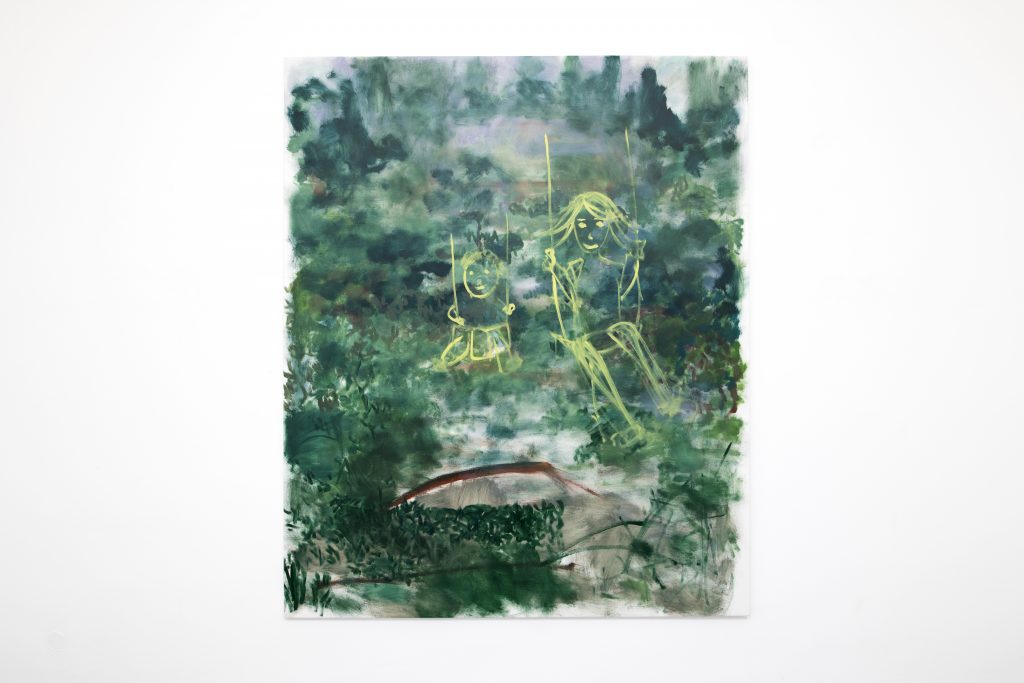

Swinging, 2021

Oil on canvas

220 x 183 cm

Installation view

Sleepy Hollow (Maui), 2022

Oil on canvas

28,5 x 31 cm

Installation view

Hometown, 2021

Oil on canvas

136 x 170 cm

Westchester (Hawaii), 2022

Oil on canvas

28,5 x 33 cm

Hudson Valley (Sunset), 2022

Oil on canvas

18,5 x 15,5 cm

Flowers, 2022

Oil on canvas

23,5 x 18,5 cm

Hudson River (Oahu), 2022

Oil on canvas

28,5 x 31 cm

Trevor Shimizu

Luminism (American art style)

Die Bilder, die Trevor Shimizu 2022 in der Galerie Christine Mayer zeigt, stellen sich als Gewebe dar oder als Feld. In größeren Bildern wie Hometown scheint die Malerei an den Grenzen der Leinwand nicht haltzumachen. In kleineren wie Westchester (Hawaii) scheint sie in deren Mitte zu schweben. Wie in einem Wald können wir uns verbergen, aber auch eine Lichtung betreten. Die Malerei bildet kein gleichmäßiges Gitter, kein regelmäßiges vorne und hinten. Oder sie erinnert an die Geschichten von Malern, die einen mit Farbe getränkten Schwamm an die Wand geworfen und im Abdruck eine Landschaft gefunden haben. Es gibt die Erklärungen, dass die Malerei Zeichen sei und Bezeichnetes, und dass Botticelli und Leonardo ihre Einbildungskraft haben spielen lassen. Wer mit Kunst vertraut ist, wird das Bild als Landschaft ebenso kennen wie das Bild einer Landschaft.

Bilder von Landschaften lassen an Orte denken oder zumindest an Topoi wie Blumen. Aber es ist nicht nur geläufig, sondern gewagt, in der Isar oder im Enzian Heimat zu finden. In der Antike ist das Leben auf dem Land ein Gegenbild zum Leben in der Stadt oder im Römischen Reich. Im Mittelalter ist die Landschaft der Hintergrund für ein Mysterium. Der amerikanische Luminism hat mit europäischer Malerei mindestens so viel zu tun wie mit amerikanischen Motiven. Der Maler Martin Johnson Heade hat auch tropische Orchideen und Kolibris dargestellt.

In dem Abstand, den wir dazu haben, werden Heades Salzwiesen fremder als der See, den Konrad Witz gegen Ende des Mittelalters gemalt hat. Dieser See ist nicht vertrauter, weil er der Bodensee ist. Der Bodensee in Der wunderbare Fischzug erscheint vielmehr in einem Licht, das nur indirekt von der Sonne, direkt aber vom Bildgrund ausgeht. Die Salzwiesen scheinen dagegen in einem natürlichen Licht zu liegen, das unruhig wirkt, weil es nur eingefangen und hergestellt werden kann als Beleuchtung.

Objektiv sind Bilder, subjektiv die Einbildung, die Bilder hervorbringt oder interpretiert. Greifbar sind Ort und Motiv, ungreifbar Licht und Natur. Dennoch wird das alles zur Natur, wenn von Stil und von Heimat die Rede ist. Diese scheinbar natürlichen Begriffe erweisen sich als hinfällig, wenn es um Landschaft als Kunst geht.

In Europa gab es bis ungefähr 1945 den Heimatstil. An den Texten von Martin Heidegger ist gewiss hinfällig, was damit zu tun hat. Dennoch ist Beiträge zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis) nicht nur als Ruine zu lesen, sondern als Bauplan. Denn ein Anfang, der als natürlicher gilt, wird nur im Hinblick auf einen „anderen“ Anfang ins Auge gefasst. Heidegger findet den sprechenden Hinweis, dass die griechische Philosophie anfängt mit dem Erstaunen. Der andere Anfang muss dagegen im Erschrecken bestehen oder sogar im Entsetzen.

Die Arbeit von Trevor Shimizu lässt sich nicht als Teil einer Tradition verstehen, von der eine erneut romantische Fortführung der amerikanischen Romantik zu erwarten wäre. Dennoch ist das Licht für Trevor Shimizu nicht weniger wichtig als für den Luminism. Eben dieses Licht aber kommt uns weder als natürliches Licht noch als Beleuchtung entgegen. Ähnlich wie James Ensor oder Andy Hope 1930 lässt Trevor Shimizu durch seine Malerei den Grund des Bildes durchscheinen. Mit dieser Kunst geht der Schrecken einher, dass das Licht der Romantik erlischt. Aber dass diese Kunst ihre Bilder trotzdem zum Leuchten bringt, ist nicht erschreckend, sondern erstaunlich.

Berthold Reiß

Trevor Shimizu

Luminism (American art style)

The paintings shown by Trevor Shimizu at Galerie Christine Mayer in 2022 present themselves as fabric or a field. In the larger paintings, like Hometown, the painting does not seem to stop at the borders set by the canvas frame. In the smaller ones, like Westchester (Hawaii), the painting seems to float in the centre instead. Like in a forest, we can hide, but we can also reach a clearing. Painting does not form a regular grid, a regular front and back. Or it reminds us of the stories of painters who threw a paint-soaked sponge on the wall and found a landscape in the imprint. There are explanations that painting is simultaneously signifier and signified, and that Botticelli and Leonardo gave their imaginations free rein. Those who are familiar with art will know the picture as landscape just as well as the picture of a landscape.

Images of landscapes make us think of places or at least of topoi such as flowers. Yet, it is not only familiar but daring to find a home in the Isar river or gentians. In antiquity, life in the countryside was a counter-image to urban life or life in the Roman Empire. In the Middle Ages, landscape constitutes the backdrop for a mystery. ‘American Luminism’ has at least as much to do with European painting as it has with American motifs. The painter Martin Johnson Heade also depicted tropical orchids and hummingbirds.

Given our current chronological distance, Heade’s salt marshes become more estranged than the lake that Konrad Witz painted towards the end of the Middle Ages. This lake is not more familiar because it is Lake Constance, but rather because Lake Constance in Der wunderbare Fischzug (The Miraculous Draft of Fishes) appears in a light that emanates only indirectly from the sun, but directly from the picture’s background. The salt marshes, on the other hand, seem to be engulfed in a natural rather restless light because only as illumination can it be captured and produced..

Images are objective, the imagination that yields or interprets images is subjective. Place and motif are tangible, light and nature are intangible. Yet all of these become nature when we speak of style and homeland. These seemingly natural ideas prove to be unsustainable when it comes to landscape as art.

In Europe, the ‘Heimatstil’ (Domestic Revival) existed until about 1945. In regards to this, Martin Heidegger’s texts, which revolve around this very notion, are certainly also unsustainable. Nevertheless, Beiträge zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis) is to be read not only as a ruin but as a blueprint. For a beginning that is deemed to be natural is only conceived in terms of an “other” beginning. Heidegger finds the telling indication that Greek philosophy begins with astonishment. In contrast, the other beginning must opposingly consist of fright or even horror.

Trevor Shimizu’s work cannot be understood as part of a tradition from which a renewed romantic continuation of ‘American Romanticism’ can be anticipated. Nevertheless, light is no less important to Trevor Shimizu than it was to ‘Luminism’. But it is precisely this light that reveals itself to us neither as natural light nor as artificial illumination. Similar to James Ensor or Andy Hope 1930, Trevor Shimizu allows for the picture’s background to shine through in his paintings. With such art comes the horror that the light of romanticism is extinguished. Yet, the fact that this art still makes its pictures shine is not frightening, but astonishing.

Berthold Reiß

translated by Melanie Waha