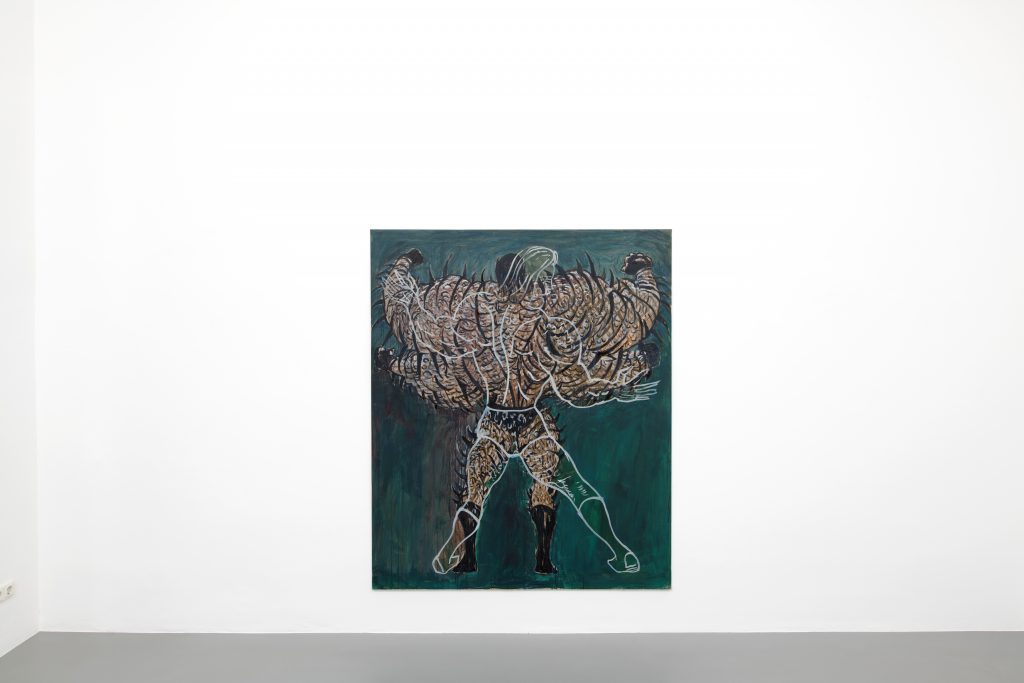

Installation view

Installation view

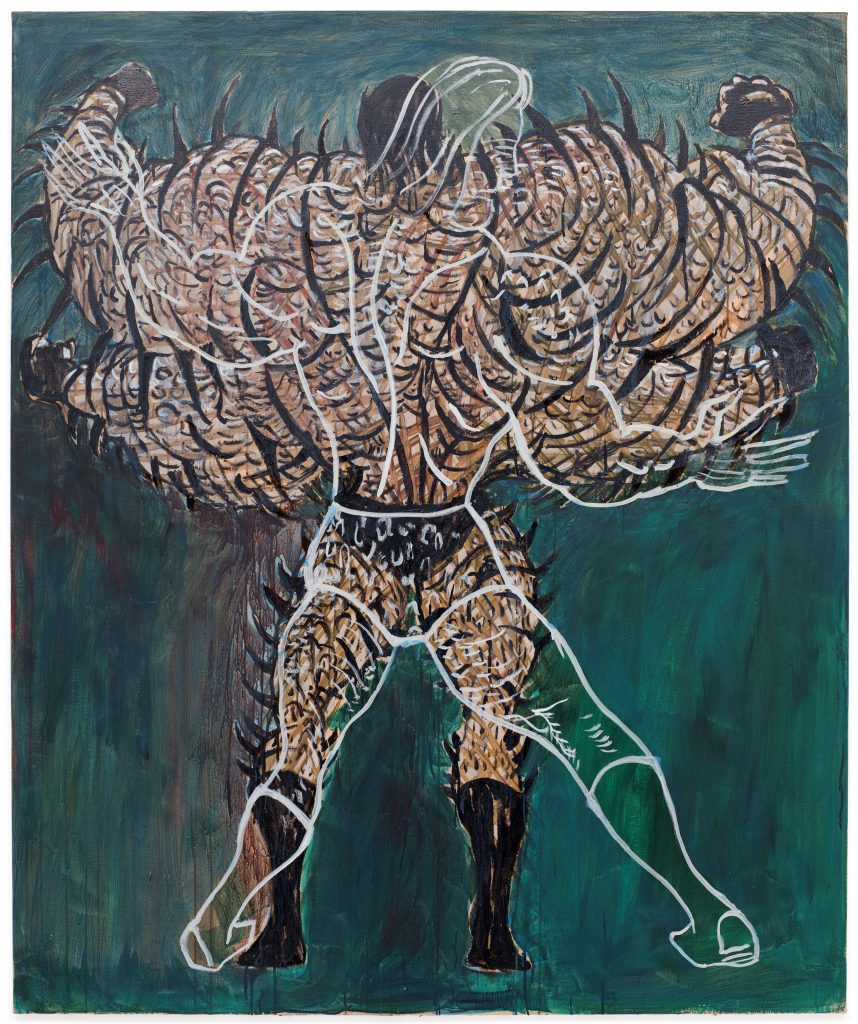

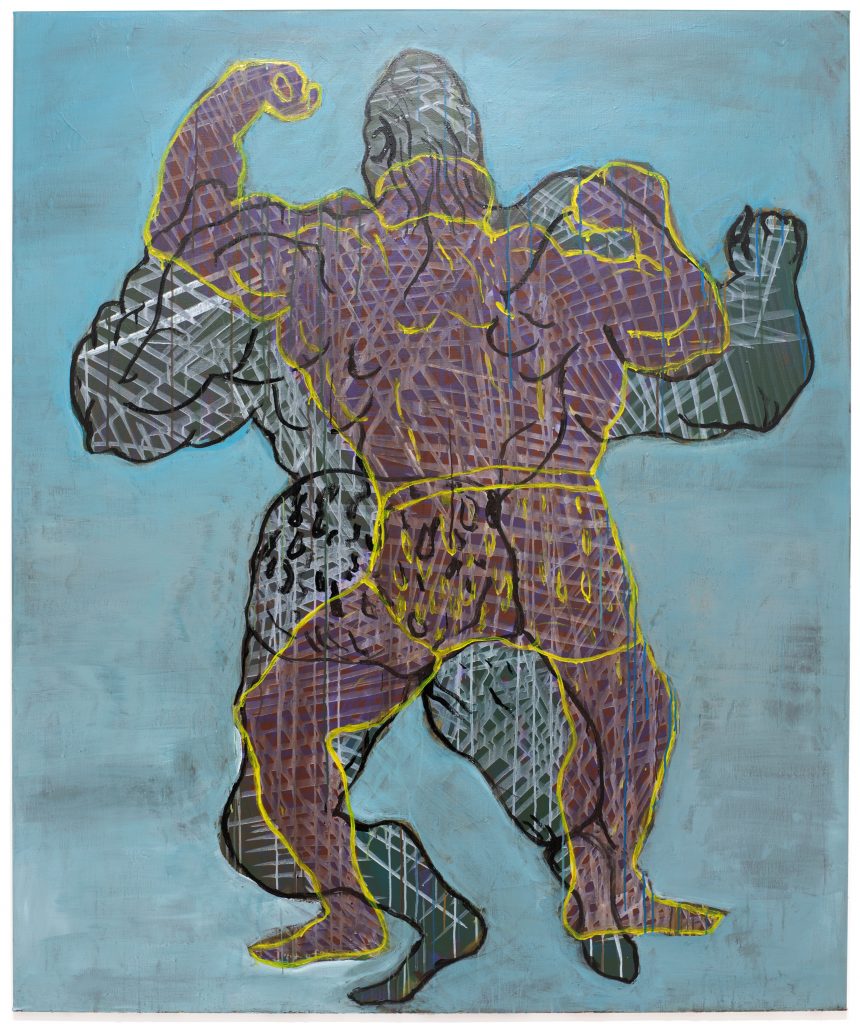

Orbital Hypertrophies IV, 2022

Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 150 cm

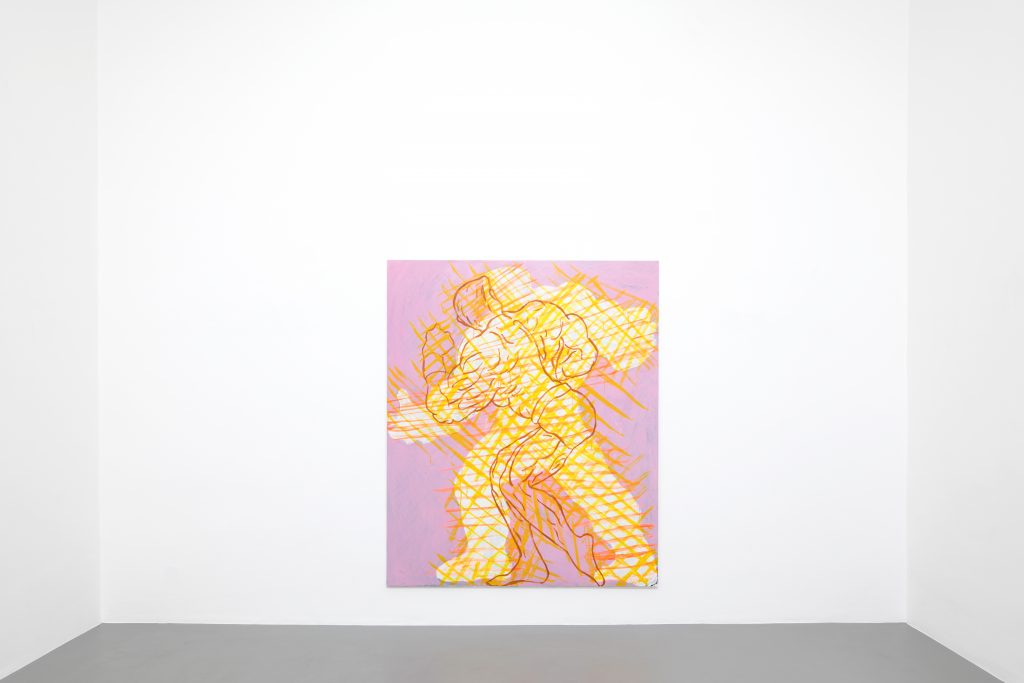

Installation view

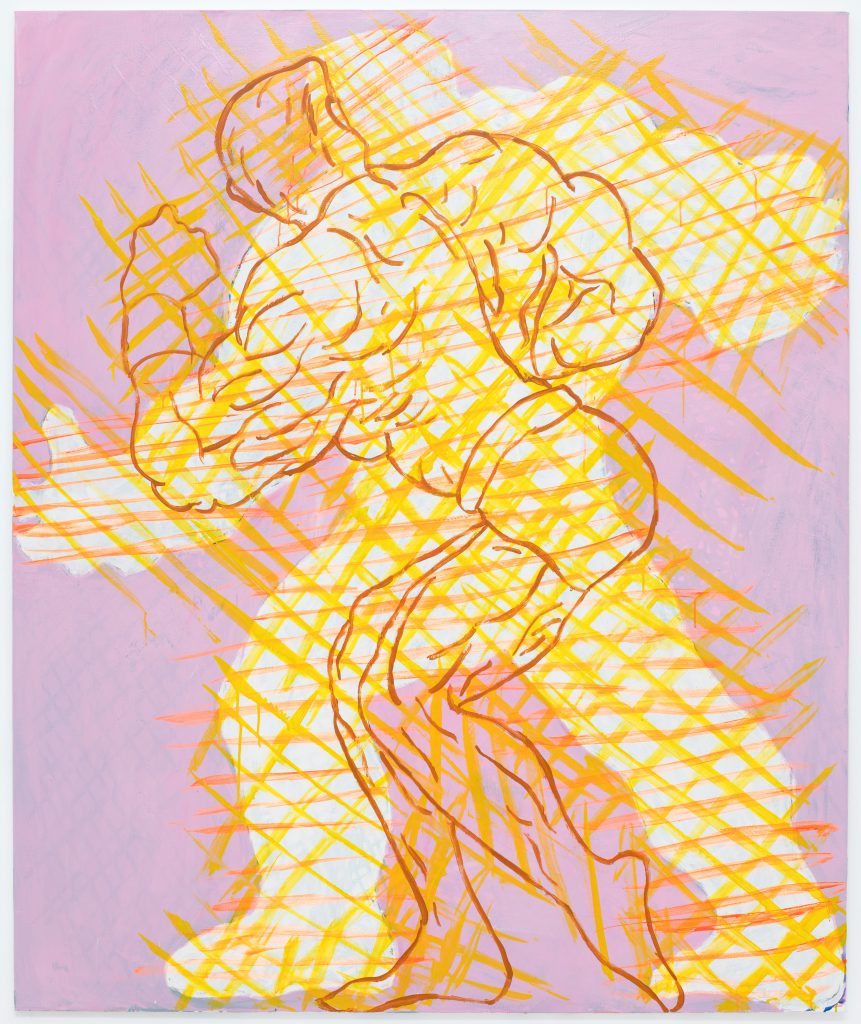

Orbital Hypertrophies VI, 2022

Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 150 cm

Installation view

Installation view

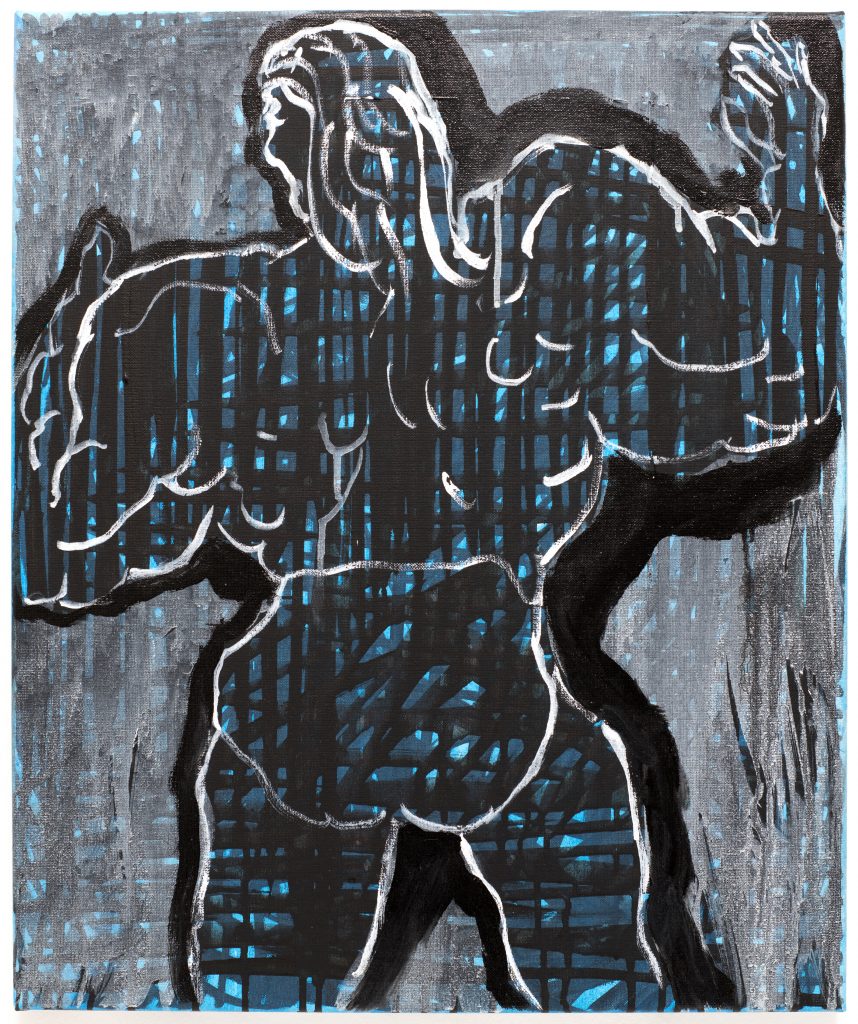

Orbital Hypertrophies III, 2022

Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 150 cm

Orbital Hypertrophies V, 2022

Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 50 cm

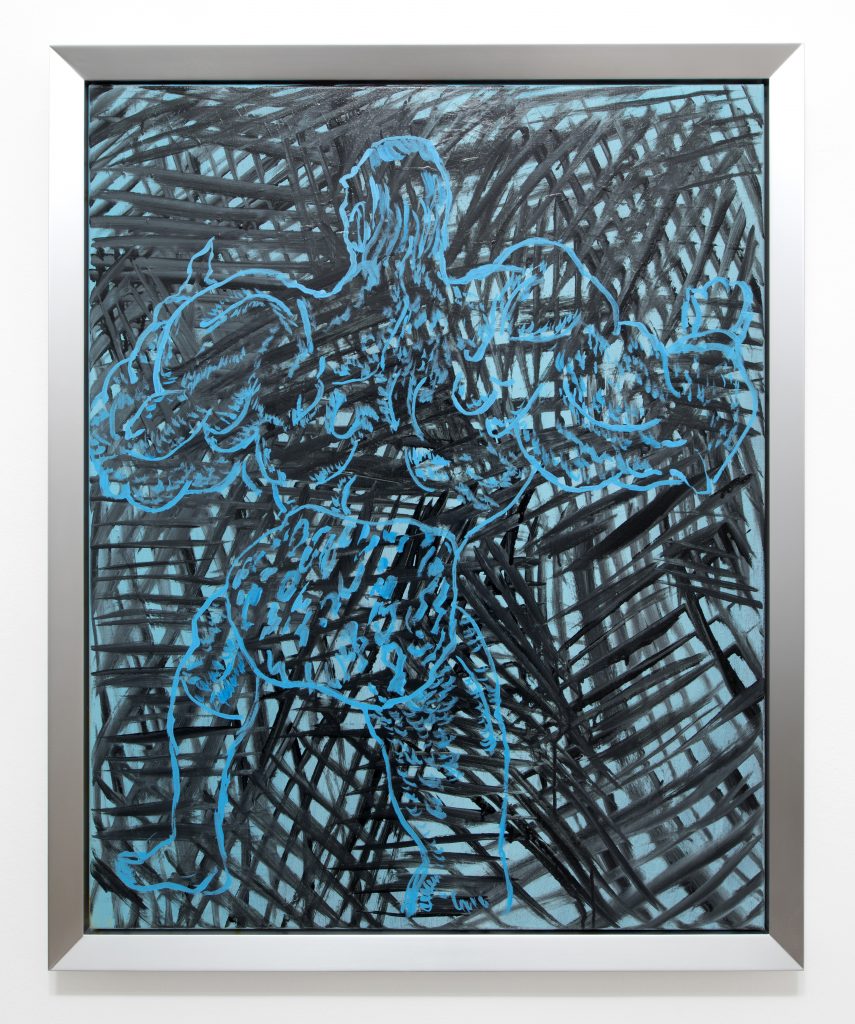

Orbital Hypertrophies I, 2022

Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 40 cm

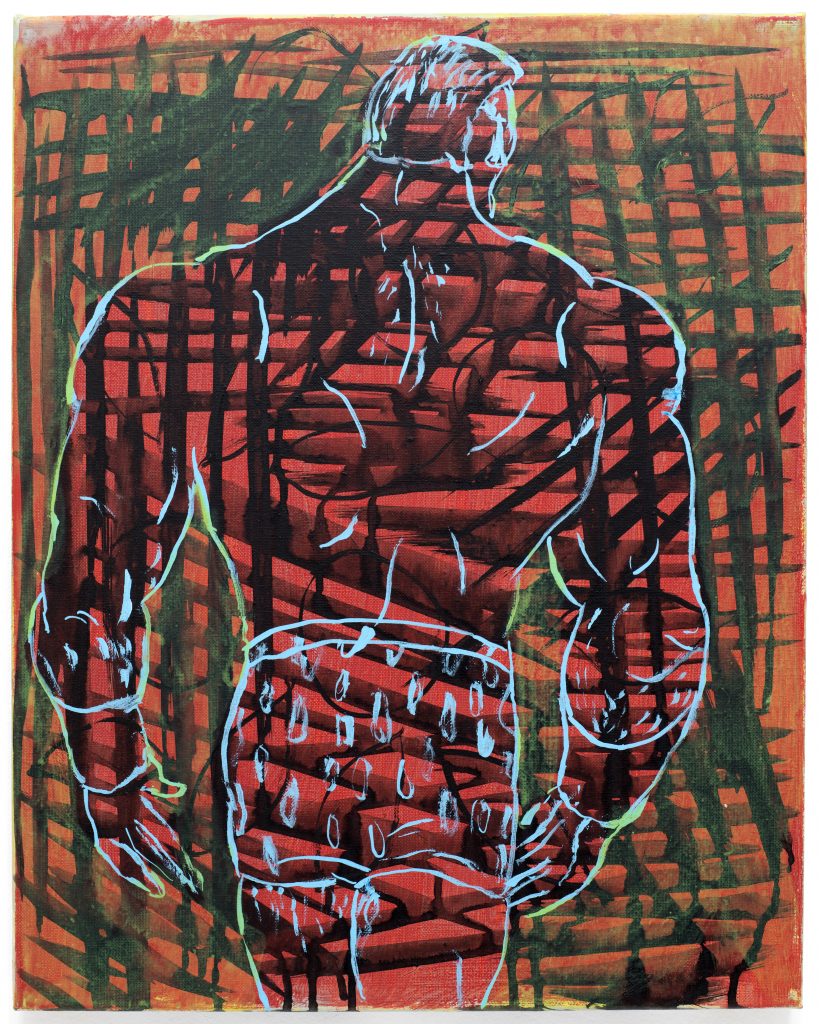

Orbital Hypertrophies II, 2022

Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 80 cm

Andy Hope 1930

A HANDFUL OF GRAVITY

Was haben wir noch in der Hand, wenn wir vor allem die eigene Schwere erfahren und den Umlauf im Gleichen? Andy Hope nennt seine Bilder in der Ausstellung A Handful of Gravity in der Galerie Christine Mayer Orbital Hypertrophies. Wahrscheinlich würden wir aus dem Orbit nicht hypertroph, sondern an Gewicht und Gewebe gemindert zurückkehren. Aber wir drehen uns auch in dem Walzer, den Stanley Kubrick nach oben versetzt und die Anziehung, die uns mit Andy Hope verbindet, ist der, die uns an die Erde fesselt, entgegengesetzt. In einem Text von 2000 besteht sie in der „Leichtigkeit, etwas zu machen, anstatt etwas zu produzieren“. Und als Lothringer 13 im gleichen Jahr Raumvorstellungen zeigte, waren von Andy Hope unter anderem sich küssende Galaxien zu sehen. Die Titel von 2022 weisen auf Kosmos und Körper, nicht auf Einsamkeit oder Melancholie. Und schließlich fängt Andy Hope da an, wo die Produktion der Kulturindustrie aufhört: Die Orbital Hypertrophies sind gemalt, aber nur zur Hälfte Gemälde. Wer Tintoretto sieht, sieht zugleich Jack Kirby.

Auch alle, die davon angezogen sind, können diese Attraktion fassen in dem, was Sergej Eisenstein die Montage der Attraktionen nennt. Auch Andy Hope setzt seine Mittel als „eine kraft ihrer formalen Besonderheiten auf Bewusstsein und Gefühl der Zuschauenden gerichtete Anordnung von Schlagbolzen“ ein. Damit betritt seine Kunst den „Kreis der einwirkenden Künste“, in den für Eisenstein das Theater nicht, sehr wohl aber der Zirkus gehört. Andy Hope hat einmal eine seiner Zeichnungen Nihilist Circus genannt und damit selbst die Frage gestellt, was denn bewirkt werden soll? Provokationen können das Gewicht nur vermehren, das auf der Gegenwart lastet. Am 11. Mai 2022 hat Boris Groys gesagt: „Wir leben in einer Zivilisation, die nur die Gegenwart als Realität akzeptiert. Eingeschlossen in unseren Generationenkerker leben wir nur hier und jetzt.“ Ein Berufsjugendlicher wirft jeden Tag einen Stein in den gleichen Teich. Für Andy Hope aber ist es kein Leiden, sondern ein freier Zug, Illusion und Desillusion in eins fallen, zu einer Gegenwart werden zu lassen. Die Orbital Hypertrophies legen den Kampf offen, der auch im Kerker noch dauert. Der Mensch scheint mit sich allein, aber doch konfrontiert mit dem Anderen, der er auch ist. Tatsächlich kommt es zu jenem „krampfartigen Ausspannen aller Seelenflügel“, das Nietzsche hat kommen sehen.

Die Gestalten sind aber vor allem darum nicht allein, weil sie mit dem Anderen verwoben gezeigt sind, das sie als Bildraum wie Weltraum umgibt. Und dieses Gewebe ist längst nicht so starr wie das Gitter, das sich mit dem Kerker verbindet. Zwar greift Andy Hope auf ein Mittel zurück, in dem sich die Schwere und die Mechanik abendländischer Bildproduktion in der Neuzeit, erst recht in ihrer jahrhundertelangen Reproduktion im Kupferstich, manifestiert haben. Aber anders als Albrecht Dürer setzt Andy Hope das crosshatching oder die Kreuzschraffur nicht vor allem ein, um Körper zu beschreiben, sondern die Leere. Diese scheint weniger bildimmanent gefüllt als bildtranszendent eröffnet. Man kann darauf hinweisen, dass Günther Förgs Gitter Munchs Bettdecke beschreiben, die spitzen, schilfblattförmigen Züge Hans Hartungs dagegen den Weltraum. Aber dieser Hinweis geht an dem Augenblick, der sich als A Handful of Gravity einstellt, genauso vorbei wie der Hinweis, dass der Dichter Arthur Cravan im Boxring gekämpft hat. Jener Raum und diese Figur wirken vielmehr so zusammen, dass sie sich im Wechsel opak darstellen und transparent. Diese Einwirkung auf die Betrachtenden, oder dass uns nicht nur ein Bild begegnet, sondern ein Wille, dass wir nicht nur zu sehen meinen, sondern zu hören, weist auf ein Gleichgewicht hin, das so allgemein ist, dass es erst bemerkt wird, wenn es gestört ist.

Der chinesische Philosoph Zhao Tingyang führt aus, dass der legendäre Herrscher Zhuan Xu um 2300 vor Christus eine „Unterbrechung des Kontaktes der Erde zum Himmel“ angeordnet habe. Und das Christentum könne man als „eine weltweit nachwirkende Unterbrechung des Kontaktes der Erde zum Himmel“ bezeichnen. Dennoch heißt das Buch von 2020 Alles unter dem Himmel, und der Untertitel lautet Vergangenheit und Zukunft der Weltordnung. Gegen Ende aber räumt der Autor ein, dass eine geordnete Welt noch kein gutes Leben bedeute. Daher schließt er sein Buch mit dem Hinweis auf ein ganz anderes Buch. „Die Archäologen haben zahlreiche alte Schriften in Gräbern entdeckt, das Buch der Musik war nicht darunter. Sein Verlust muss möglicherweise als Metapher aufgefasst werden.“ Viele reden von der Entzauberung der Welt, wenige davon, dass sogar das nicht möglich ist ohne Verzauberung. Andy Hope trägt zur Verzauberung bei, wenn er Bilder hervorbringt und zugleich Musik.

Berthold Reiß

Andy Hope 1930

A HANDFUL OF GRAVITY

What do we still have in our hands, when we experience our own gravity first and foremost and find ourselves orbiting within the same space? In the exhibition A Handful of Gravity at Christine Mayer Gallery, Andy Hope refers to his paintings as Orbital Hypertrophies. We probably won’t return from this orbit hypertrophied, but weakened in weight and body tissue. Yet, we also spin within the waltz pushed upwards by Stanley Kubrick, while the gravitational pull that binds us to Andy Hope is the opposite of the force which physically ties us to earth. In a 2000 text, such consists of the “ease of making rather than producing”. And when Lothringer 13 displayed Raumvorstellungen in the same year, Andy Hope showed a work of kissing galaxies, among others.

The 2022 titles point to the cosmos and physical bodies, not loneliness or melancholy. And finally, Andy Hope begins where the production of the culture industry ends: the works Orbital Hypertrophies are painted, but only to a certain extent paintings. Anyone who sees Tintoretto also sees Jack Kirby.

Everyone, who is drawn to this can grasp its attraction through what Sergei Eisenstein refers to as the montage of attractions. Andy Hope also uses his tools as “an arrangement of firing pins directed by virtue of their formal peculiarities towards the consciousness and feelings of the spectators”. His art thus enters the “circle of influencing arts”, to which, according to Eisenstein, theatre does not belong, but the circus does very well indeed. Andy Hope once called one of his drawings Nihilist Circus, thereby asking the question of what is actually to be achieved? Provocations can only increase the heaviness that weighs upon the present. On May 11, 2022 Boris Groys said: “We live in a civilization that only accepts the present as reality. Locked up in our generational dungeons, we only live in the here and now.” Every day, a professional teenager throws a stone into the same pond. For Andy Hope, however, it is not about suffering, but a free move, allowing illusion and disillusionment to become one – to become one in the present. The works Orbital Hypertrophies reveal the struggles that will continue even in the dungeons. Man seems alone with himself, but is also confronted with the other, who he is, too. In fact, it leads to the “spasmodic unclamping of all of the wings of the soul” that Nietzsche saw coming.

Above all, however, the figures are not alone because they are shown interwoven with the other, namely the pictorial space that surrounds them like outer space.And this web isn’t nearly as rigid as the lattice that is connected to the dungeon. It is true that Andy Hope resorts to a medium in which the heaviness and mechanics of the Western image production have manifested themselves in the modern period, especially in the centuries-long reproduction of copperplate engravings. But unlike Albrecht Dürer, Andy Hope does not primarily use crosshatching to describe bodies, but emptiness instead. The picture space seems to be filled less immanently but is opened up transcendently. It can be pointed out that Günther Förg’s grid describes Munch’s bedspread, while Hans Hartung’s pointy, reed-shaped brushstrokes depict outer space. But this clue misses the moment which reveals itself as A Handful of Gravity, as does the clue that the poet Arthur Cravan fought in the boxing ring. Rather, this space and this figure interact with each other in a way, which allows them to alternately appear opaque and transparent. This impact on the viewer, or that we encounter not just an image, but a will that we think we not only see but also hear, indicates an equilibrium so general that it remains unnoticed until it is is disturbed.

The Chinese philosopher Zhao Tingyang explains that around 2300 BC the legendary ruler Zhuanxu ordered an “earth’s contact with the sky to be severed”. And Christianity could be described as “a worldwide lasting interruption of the contact between heaven and earth”. Still, the 2020 book is called Alles unter dem Himmel (Everything beneath the Sky) and the subtitle is Vergangenheit und Zukunft der Weltordnung (The Past and Future of the World Order). Towards the end, however, the author admits that an orderly world does not simply mean living a good life. Therefore, he closes his book with a reference to a completely different book. “Archaeologists have discovered numerous ancient writings in tombs, the Book of Music was not among them. Its loss may need to be taken as a metaphor.” Many speak of the disenchantment of the world, while a few say it becomes an impossibility without enchantment. Andy Hope adds to the enchantment when he creates images and music at the same time.

Berthold Reiß

Translated by Melanie Waha