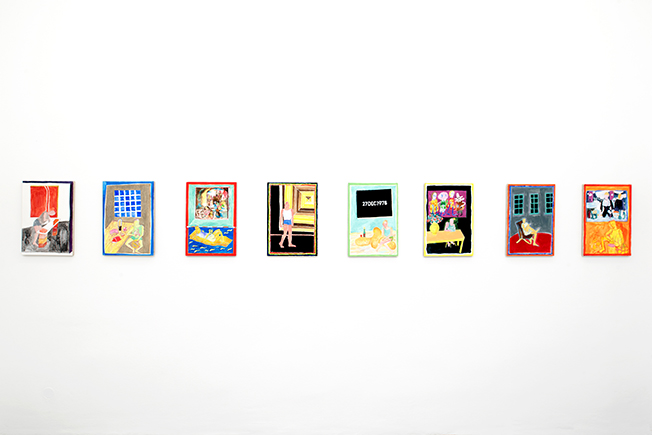

Installation view

Installation view

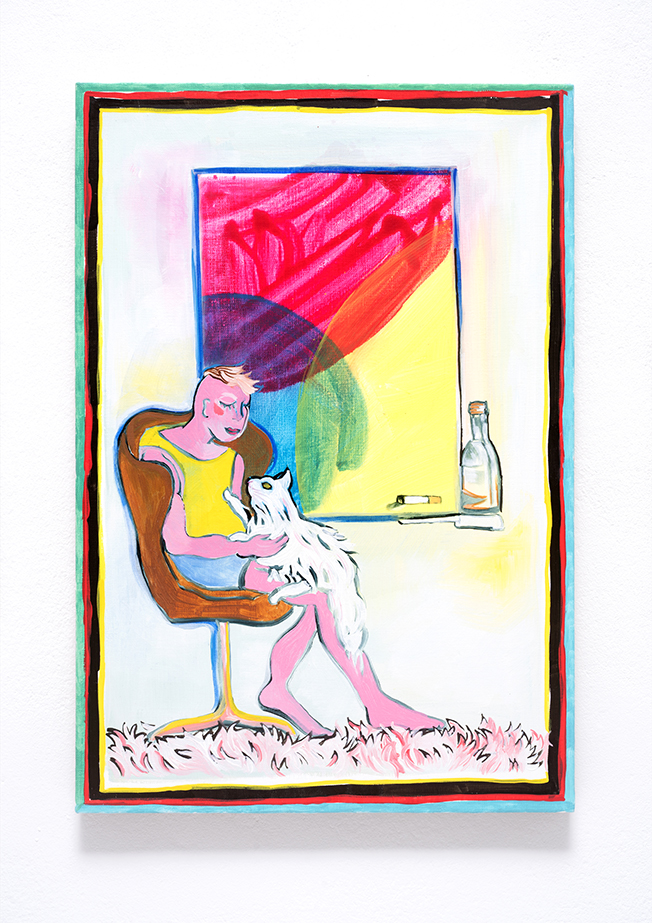

Flauschteppich, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Artist trying to figure something out, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

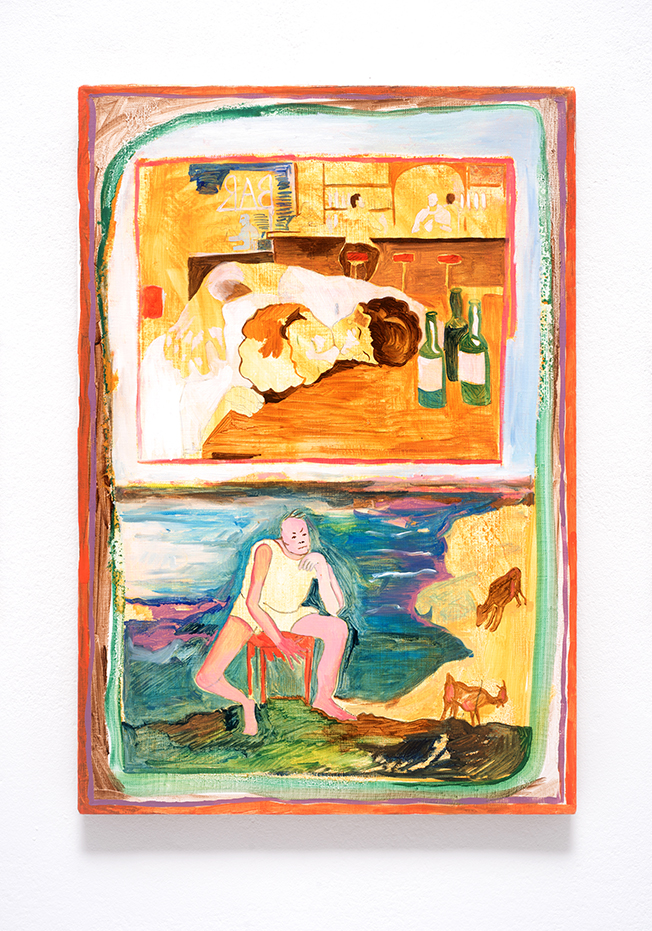

In Arkadien, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

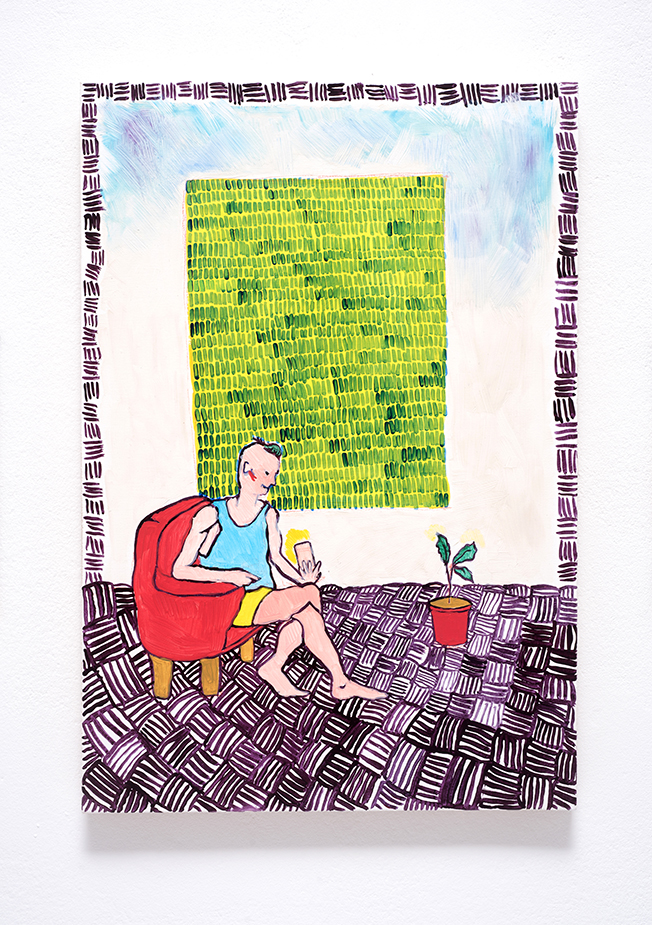

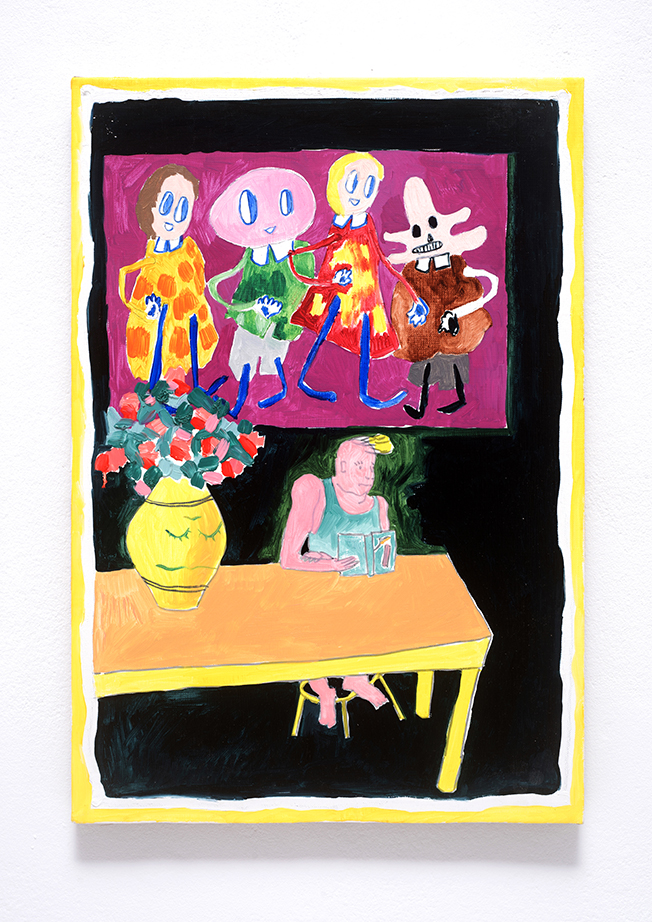

Artist posting on Social Media, 2018, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Installation view

Theorie und Praxis, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

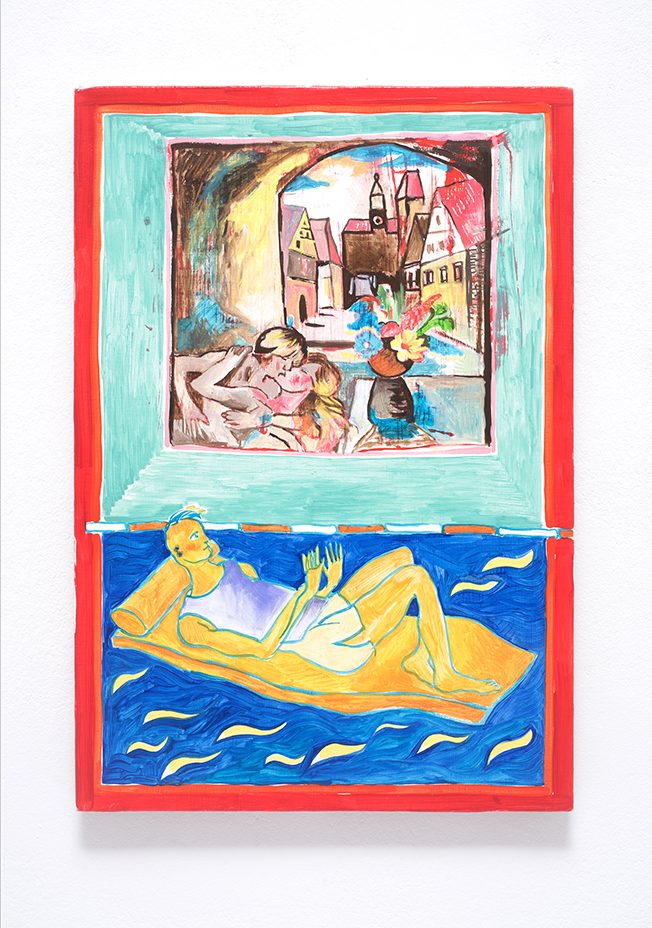

Poolfantasie, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

X, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

L‘usage des plaisirs, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Op Agnes, 2018, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Summer Heat und Dornröschenschlaf (immer diese Vorahnungen), 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

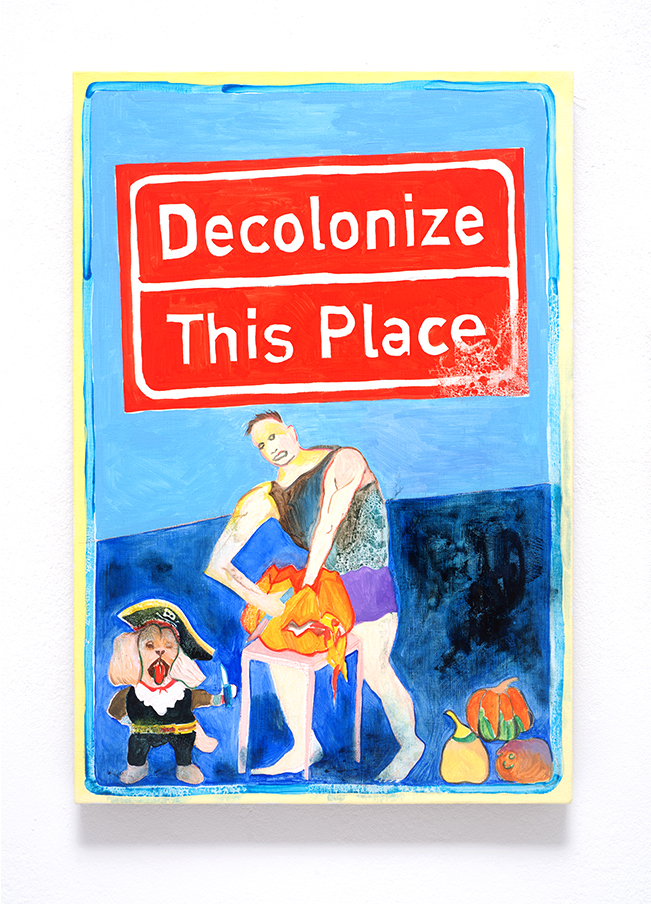

Decolonize this Place, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

West Highway, 2019, carton, sugar glass, micro controller, LED matrix

35 x 28,5 x 6 cm

Papagei, 2020, ceramics, glaze, carton, plastic, electronics, nails

30 x 10 x 6 cm

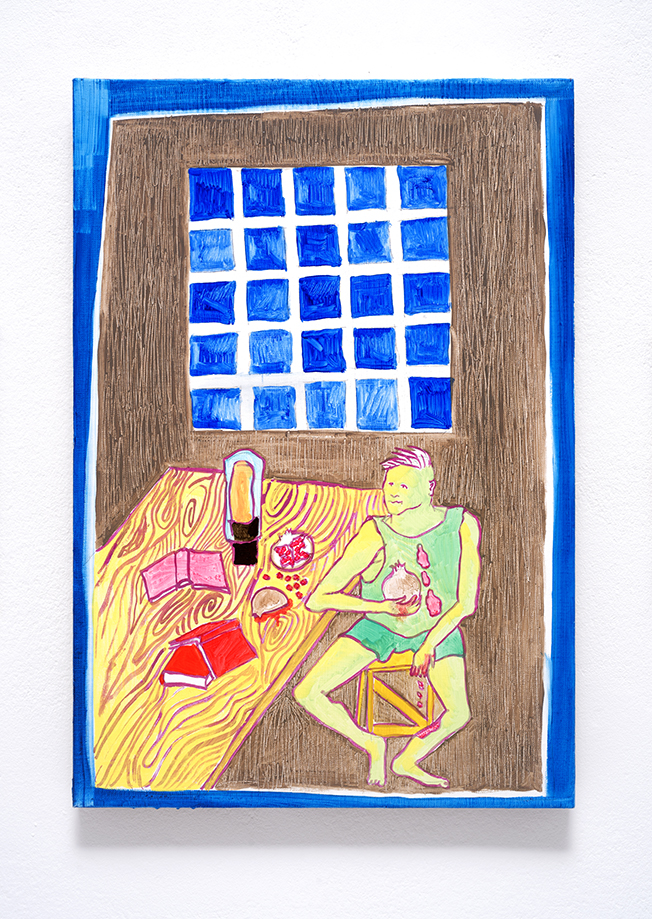

Studierzimmerfantasie mit wichtigen Unterlagen, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

At your service, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Auf Recherchetour, 2018, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

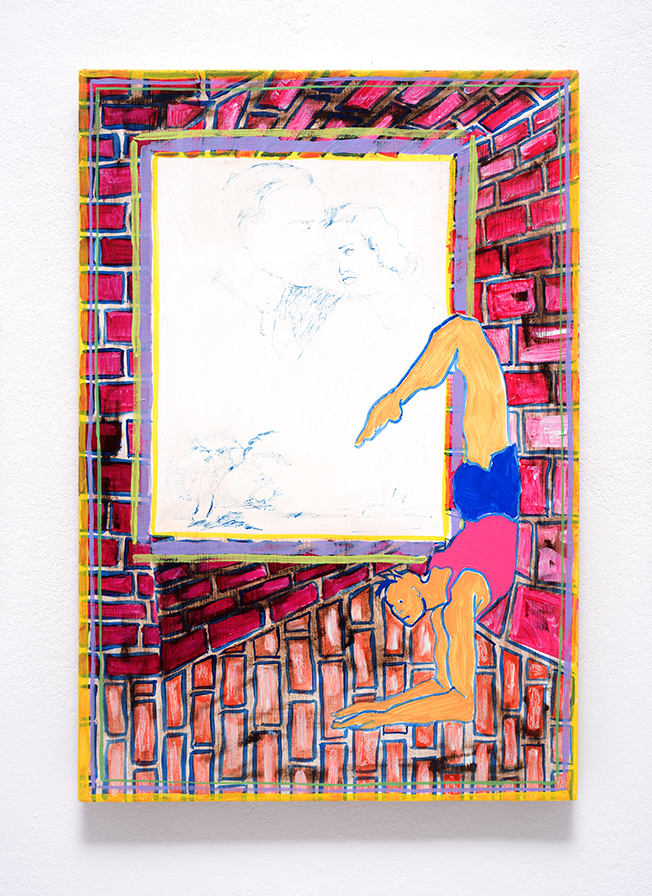

Tightrope Painting, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

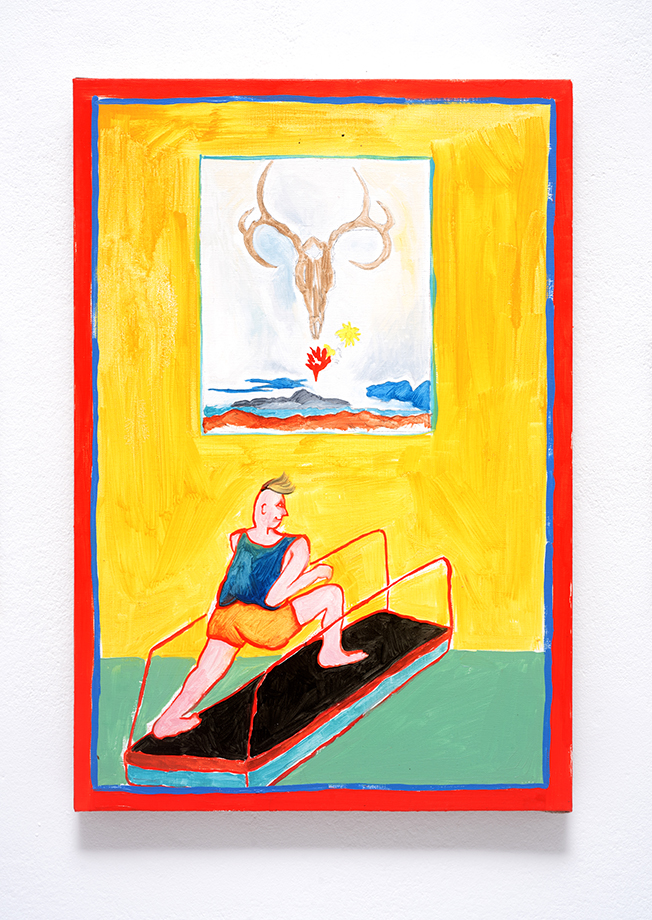

Long Run, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

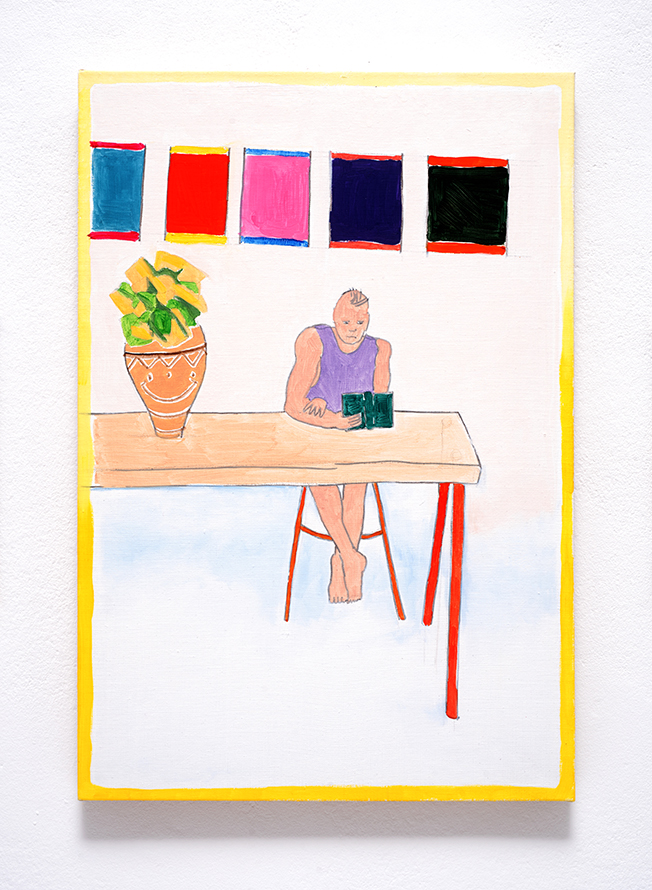

Life Goals, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

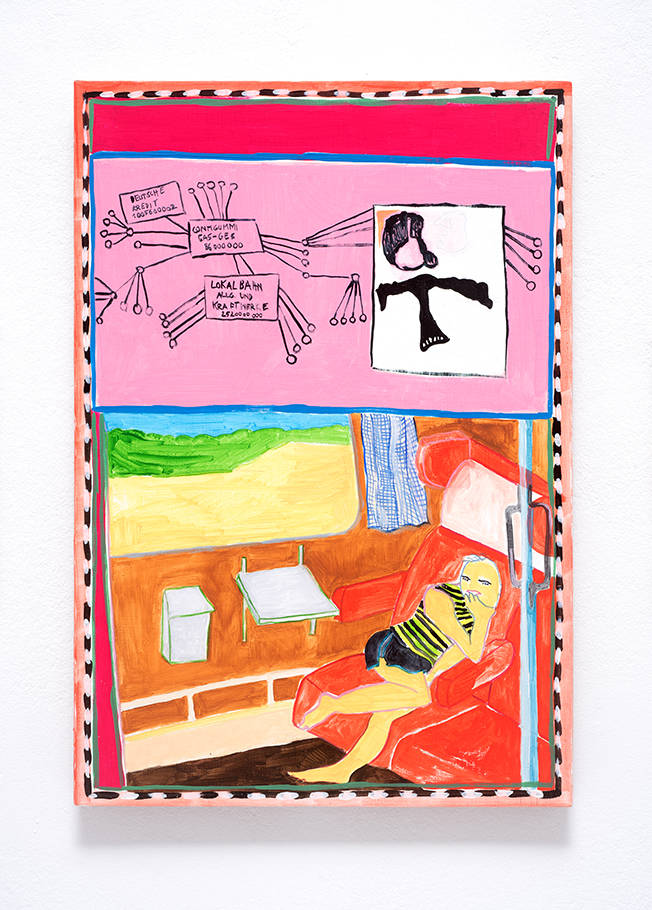

Pendolino, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Schleckphone mit erweitertem Speicher, 2019, ceramics, sugar glass, food clouring

27 x 17 x 5 cm

Vampir, 2019, ceramics, glaze, sugar glass, vinyl gloves

28 x 11 x 10 cm

Downtown, 2020, carton, sugar glass, micro controler, LED matrix

64 x 22,5 x 3,5 cm

2 Perfect Circles, 2019, engine, ceramics, glaze, epoxy resin, metal elements

Ø 100 cm; H 300 cm

Dreamboat, 2019, soundpiece, plastic box, button, electronics

Ø 11,5; H 8 cm

Smoker, 2019, ceramics, glaze, sugar glass, cigarette, food colour

29,5 x 16,5 x 11 cm

Installation view

Zum Beispiel, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Future Forecast, 2018, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Kanonfantasie, 2018, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Fortune Teller, 2019, ceramics, glaze, sugar glass, food colouring, micro controller, LED matrix

30 x 20 x 4 cm

Times of the day, 2018, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

Getting in Shape, 2019, oil on canvas

48,26 x 33,02 cm

I had this dream the other night: I worked as a waitress in an American diner and this super famous curator came in together with Patti Smith. I was wearing a doily apron and approached them on roller skates, balancing a pitcher of black coffee in my right hand, and a notebook and a pen in my left. I asked them to place their order. Patti wanted carrot soup. Her companion ordered a steak. I explained that I could do the steak well done, medium or rare, however he wanted, and recommended the medium version. He insisted on getting it well done and I rolled away with a really uncanny feeling of being a vegetarian who has to grill a steak for too long. When I rolled back to the table, I balanced a bowl with carrot soup and a plate with a large T-Bone steak in my hands. About a meter away from my guests, I stumbled and tumbled, the steak flew away like a frisbee and the soup spurted upwards in slow motion.

Justin Lieberman: I admire that you allow political slogans to remain in your work such as on the t-shirt you wear on the invitation card, for example. This is a contradiction which is too much to bear for many artists. It was too much for Immendorf. He quit the party and devoted himself to Art with a capital A. Or maybe we should say with Capital’s “A”. Can you speak about the shape of the conjunction between politics and art which you imagine?

Kristina Schmidt: As artists, we work in proximity to a nearly unrestricted global market functioning accordingly to capitalist rules. This links to politics almost automatically. It is concerning and I find it crucial to not ignore this. There are a lot of things going on in the art world right now – just to mention one example, political protest from groups like Decolonize This Place removed weapon manufacturer Warren Kanders from the Whitney Museum’s board. The shirt I wear on the card was a gift from the group New Sanctuary Coalition. They provide emotional and legal support for people targeted by ICE. When I was invited to contribute work to a one-day street sale show one block from their office in SoHo, I transformed cheap New York tourist shirts into unique pieces by adding a screen-print to them. I used them as vouchers for entering a lottery. The main prize was one of my paintings and the money we raised was donated to support the work of NSC. The slogan on the shirt is totally unspecific and to wear it may even change the meaning. I like how layers of consumerism, object-making and advertising overlap each other.

J.L.: The paintings are self-portraits of you as a super muscled bodybuilder doing things in your studio or visiting places and events. It seems like there is a lot going on in each one. There are depictions of other art in them too. I am just going to choose one to start with. Tell me about the tightrope painting.

K.S.: The tightrope painting re-imagines Carl Spitzweg’s 1839 painting “Der arme Poet” [The poor poet] with the addition of a figure on a purple tightrope balancing over the purple framing line that divides the painted painting from the painted blue background. The Spitzweg painting is a stereotypical icon of the poor artist surviving under miserable conditions. When Spitzweg exhibited it first at Munich Kunstverein, it was rejected for being both romantic and flavorless. The first critics were so harsh that Spitzweg stopped signing his paintings with his name and instead used a cypher (a bun with his initials, the “Spitzweck”). “Der arme Poet” is still the Germans’ favorite painting right after the Mona Lisa, and in 2008 the Deutsche Post published a commemorative stamp with the motif. Spitzweg’s audience is quintessentially middle-class, he was one of Hitler’s favorite artists and was to be included in his Wannabe Postwar Collection. The original painting existed in several versions, the one in the Berlin Nationalgalerie was stolen and later given back as part of a political action by Ulay in 1976; an early sketch of the painting was sold for 542.500 $ at Sotheby’s in New York and is now on view in Milwaukee. The figure balancing on the tightrope is either skinned or wearing a biomechanical bodysuit. They lean backwards and a little bit to the right in order to keep the balance. It’s advantageous that the figure is buff, they need a lot of strength to stay on the tightrope. Some balance might be projected upwards from the umbrella that serves the poor poet as a protective shield against water dripping down from the ceiling.

J.L.: There are lots of poems in your work. Can you talk about how poems work? How do you approach a poem?

K.S.: I feel drawn to fragmentary and short forms in general, such as rhymes, songs, short stories, anecdotes, advertisements, jingles, infomercials, flyers, postcards, memes. I like sharp-edged language and the way it unfolds when it is explored. I feel like visual art, especially painting and those forms or writing, works in similar ways. They are clearly framed in terms of the material but reach out beyond these borders. My attention span is rather short. Instead of worrying about it, I decided that this suits the world of social media, Instagram, commercial art and self-promotion. Repetition plays a role; I want my time-based works to be watched more than once. It would be awesome to make them work like a lava lamp – something that sucks you in for some time and spits you out after. The melodies or lyrics of my songs are often fragments borrowed from or inspired by pop music, advertisement, military propaganda or musicals. The dreamboat song tells you a short story about desires and it’s ultimately annoying. It pairs up with the parrot, a small sculpture which listens to the viewer.

_______________________________________

Neulich hatte ich diesen Traum: Ich war Kellnerin in einem amerikanischen Diner und dieser superberühmte Kurator kam zusammen mit Patti Smith durch die Tür. Ich kam ihnen in Spitzendeckchen-Schürze und auf Rollschuhen entgegen, in der rechten Hand eine Kanne mit schwarzem Kaffee und in der linken ein Notizbuch und einen Stift. Ich bat die beiden, ihre Bestellung aufzugeben. Patti wollte Karottensuppe. Ihr Begleiter bestellte ein Steak. Ich erklärte, dass ich das Steak gut durchgebraten, medium oder blutig machen könnte, je nach Wunsch, und empfahl medium. Er bestand darauf, dass es gut durchgebraten sein sollte und ich rollte mit diesem unguten Gefühl davon, dass ich als Vegetarierin nun ein Steak viel zu lange grillen müsste. Als ich zum Tisch zurückkehrte, balancierte ich eine Schüssel mit Karottensuppe und einen Teller mit einem großen T-Bone-Steak in den Händen. Etwa einen Meter vor meinen Gästen verlor ich das Gleichgewicht und schlug der Länge nach hin. Das Steak flog davon wie ein Frisbee und die Suppe spritzte wie in Zeitlupe in einer Fontäne nach oben.

Justin Lieberman: Ich bewundere, dass du in deiner Arbeit politische Slogans zulässt. Zum Beispiel auf dem T-Shirt auf der Einladungskarte. Das ist ein Widerspruch, der für viele Künstler*innen nicht zu ertragen ist. Für Immendorf beispielsweise war das zu viel. Er kehrte der Partei den Rücken und widmete sich nurmehr der Kunst (Kunst natürlich großgeschrieben). Wie stellst du dir das Zusammenspiel von Kunst und Politik in deiner Arbeit vor?

Kristina Schmidt: Als Künstler*innen arbeiten wir in unmittelbarer Nähe eines nahezu uneingeschränkten globalen Marktes, der nach kapitalistischen Regeln funktioniert. Die Verbindung zur Politik liegt da auf der Hand. Mich beschäftigt und besorgt das und ich will diese Tatsache nicht ignorieren. In der Kunstwelt passiert gerade einiges – um nur ein Beispiel zu nennen: Gruppen wie Decolonize This Place protestierten gegen das Vorstandsmitglied des Whitney Museums, Warren Kanders, weil dessen Firma Safariland Tränengas herstellt, das unter anderem an der Grenze zu Mexiko gegen Migrant*innen eingesetzt wurde. Sie zwangen ihn letztlich zum Rücktritt. Das Shirt, das ich auf der Karte trage, war ein Geschenk der Gruppe New Sanctuary Coalition. Sie leisten emotionalen und juristischen Support für Menschen, die von ICE [U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement] ins Visier genommen werden. Als ich dazu eingeladen wurde, eine Arbeit für einen eintägigen Street Sale ganz in der Nähe des Büros der Organisation in SoHo beizusteuern, motzte ich billige NYC Touri-Shirts mit einem Siebdruck zu einer limitierten Edition von Einzelstücken auf. Diese wurden verkauft und dienten als Gutscheine für die Teilnahme an einer Lotterie. Der Hauptpreis war eines meiner Bilder und der Gewinn ging an NSC. Der Slogan auf dem Shirt, das ich daraufhin von NSC geschenkt bekam ist unspezifisch und vielleicht verändert es die Bedeutung sogar, wenn ich es auf der Einladungskarte anhabe. Mir gefällt, wie sich hier verschiedene Ebenen von Konsum, Produktion und Werbung überlagern.

J.L.: Die Bilder sind Selbstporträts von dir als super muskulöse Bodybuilder*in, die in ihrem Studio arbeitet oder Orte und Veranstaltungen besucht. Es scheint, als ob in jedem Bild eine Menge los ist. Manche referenzieren auch andere Kunstwerke. Was hat es beispielsweise mit dem Tightrope-Painting auf sich?

K.S.: Das Tightrope-Painting zeigt Carl Spitzwegs Gemälde „Der arme Poet” von 1839 und eine Figur, die auf einem violetten Seil über die violette Rahmenlinie balanciert, die das gemalte Bild vom gemalten blauen Hintergrund trennt. Das Spitzweg-Gemälde ist eine stereotype Darstellung des armen Künstlers, der unter prekären Bedingungen lebt. Als Spitzweg es zum ersten Mal im Münchner Kunstverein ausstellte, wurde es als romantisch und geschmacklos abgelehnt. Die Kritiken waren so vernichtend, dass Spitzweg aufhörte, seine Bilder mit seinem Namen zu signieren und stattdessen eine Chiffre (ein Brötchen mit seinen Initialen, dem sogenannten „Spitzweck”) verwendete. „Der arme Poet” ist bis heute gleich nach der Mona Lisa das Lieblingsbild der Deutschen und 2008 brachte die Deutsche Post eine Gedenkbriefmarke mit dem Motiv heraus. Spitzwegs Publikum ist bürgerlich, er war einer der Lieblingskünstler Hitlers und sollte Teil seiner Wannabe-Nachkriegssammlung werden. Das Originalgemälde existierte in mehreren Versionen: die in der Berliner Nationalgalerie wurde gestohlen und dann im Rahmen einer politischen Aktion des Performancekünstlers Ulay 1976 zurückgegeben; eine frühe Skizze des Gemäldes wurde bei Sotheby’s in New York für 542.500 $ verkauft und ist heute in Milwaukee zu sehen. Die auf dem Hochseil balancierende Figur ist entweder gehäutet oder trägt einen biomechanischen Bodysuit. Sie lehnt sich nach hinten und ein wenig nach rechts, um das Gleichgewicht zu halten. Glücklicherweise ist die Figur durchtrainiert, denn sie braucht viel Kraft, um sich auf dem Seil zu halten. Zusätzliche Balance erhält sie vielleicht vom Regenschirm, der dem armen Dichter eine Etage tiefer als Schutzschild gegen das von der Decke herabtropfende Wasser dient.

J.L.: Du arbeitest oft mit Gedichten. Wie funktioniert für dich Poesie? Wie näherst du dich Sprache?

K.S.: Ich habe einen Hang zu fragmentarischen und kurzen Formen – also Reimen und Gedichten, Songs, Kurzgeschichten, Anekdoten, Werbung, Jingles, Infomercials, Flyern, Postkarten oder Memes. Ich mag es, wenn Sprache klar und scharf ist und sich dann doch bei näherer Betrachtung entfaltet. Visuelle Kunst und besonders Malerei funktionieren oft ganz ähnlich: formal erschließen sie sich vielleicht schnell, aber das ist dann ja noch nicht alles. Meine Aufmerksamkeitsspanne ist ziemlich kurz. Anstatt mich darum zu sorgen, habe ich beschlossen, dass das der Welt von Social Media, Instagram, Werbung und Selbstdarstellung ja ganz gut entspricht. Wiederholung spielt eine Rolle: ich würde mir wünschen, dass man sich die zeitbasierten Arbeiten mehrfach ansieht. Im Idealfall wären sie wie Lavalampen: man wird davon eingesaugt und nach einiger Zeit wieder ausgespuckt. Die Melodien und Texte meiner Songs sind oft von Popmusik, Werbung, Militärpropaganda oder Musicals inspiriert oder ausgeborgt. Der Dreamboat-Song erzählt zum Beispiel eine kleine Geschichte über Herzenswünsche und Sehnsuchtsgedanken und ist dabei ziemlich nervtötend. Er macht sich gut mit dem Papagei, einer kleinen Skulptur, die zuhört und mit der Betrachter*in Kontakt aufnimmt.

translated by Jennifer Leetsch