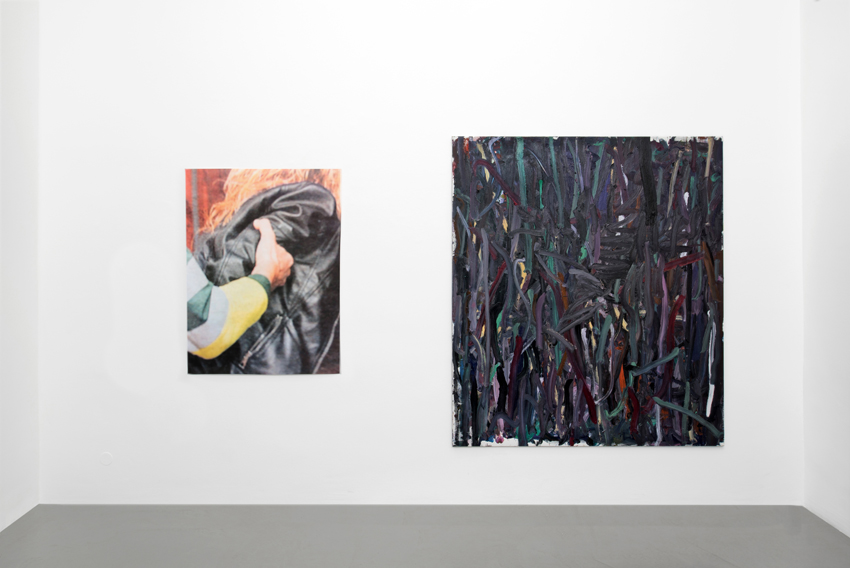

Installation view

Installation view

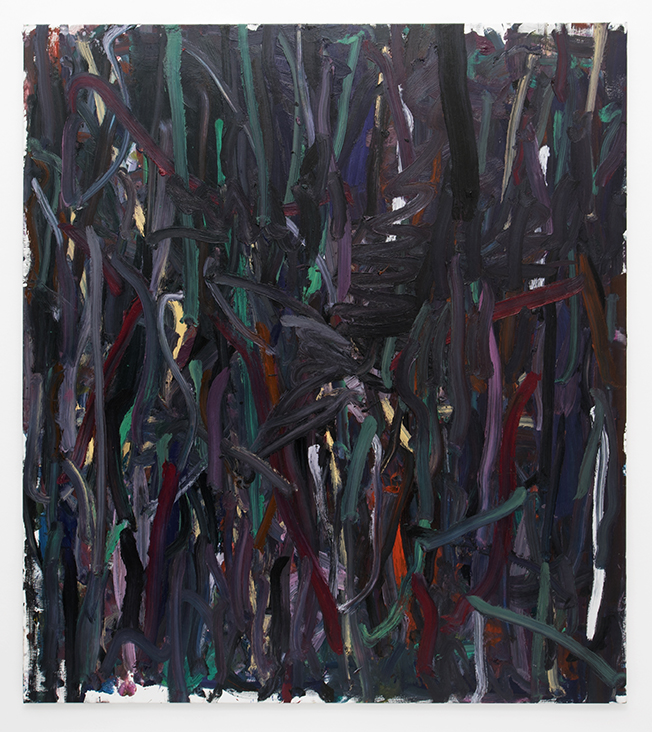

INSULAR STATE I, 2018, oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

INSULAR STATE II, 2018, oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

Installation view

Installation view

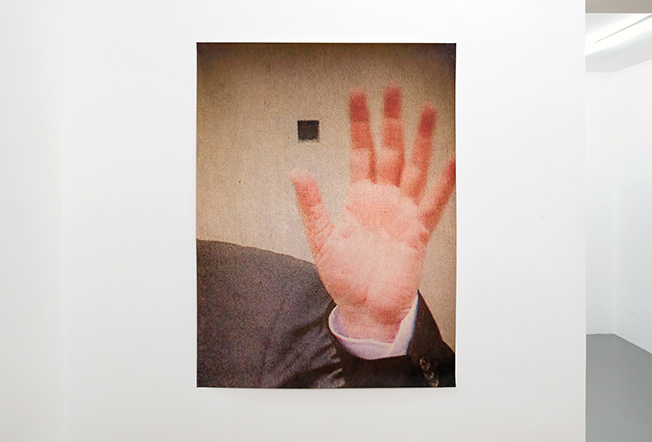

INSULAR STATE III, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

120 x 90 cm

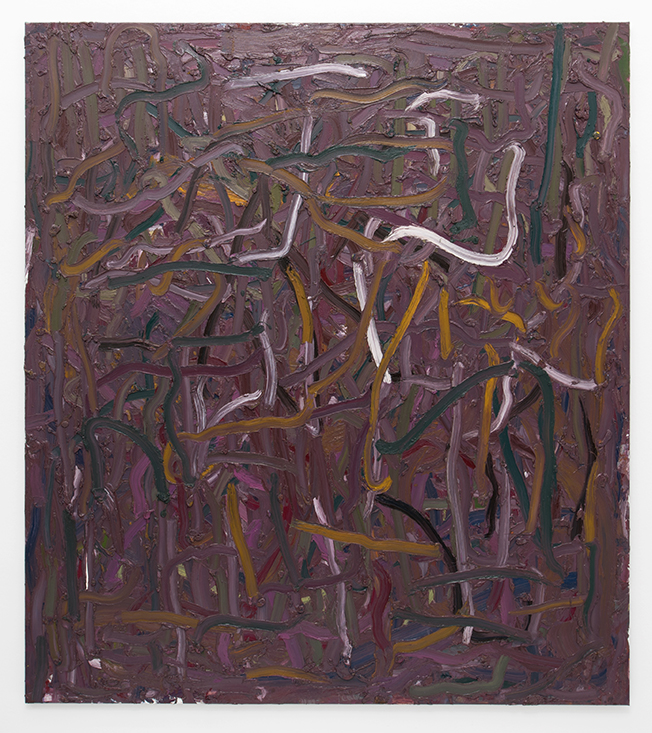

INSULAR STATE IV, 2018, oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

Installation view

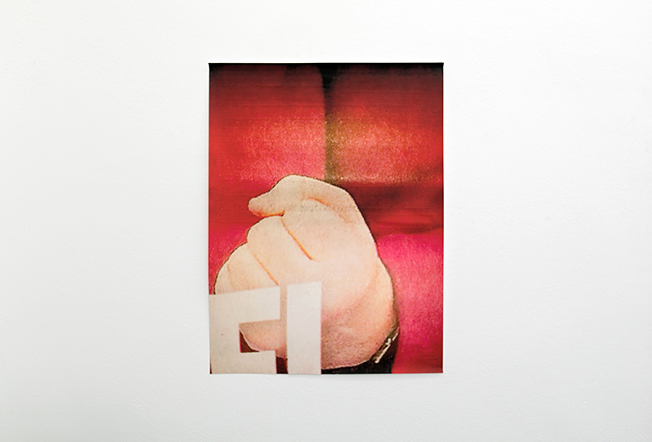

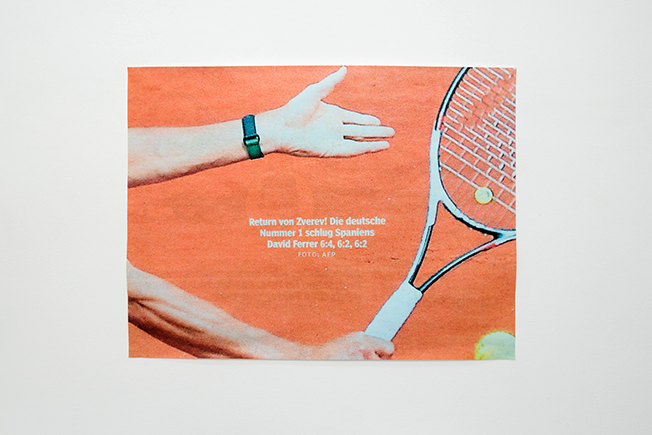

INSULAR STATE V, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

80 x 60 cm

INSULAR STATE VI, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

60 x 80 cm

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Performance INSULAR STATE, duration 3 h during the opening

INSULAR STATE VII, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

80 x 60 cm

Installation view

INSULAR STATE VIII, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

60 x 80 cm

Installation view

INSULAR STATE IX, 2018, oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

INSULAR STATE X, 2018, oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

INSULAR STATE XI, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

120 x 90 cm

Installation view

INSULAR STATE XII, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

106 x 80 cm

INSULAR STATE XIII, 2018, oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

INSULAR STATE XIV, 2018, ink jet print, edition 1/1 + 2 AP

80 x 106 cm

INSULAR STATE XV, 2018, oil on canvas

180 x 160 cm

All Work And No Play Makes Jack A Dull Boy

Thomas Poschinger im Gespräch mit Christian Malycha

CM: Du hast erzählt, dass der Titel deiner Ausstellung – »Insular State« – auf Proust zurückgeht, der sich nach dem Tod seiner Mutter vollkommen ins Private zurückgezogen hat. Obwohl er mitten im Zentrum von Paris lebte, verbrachte er seine Zeit abgeschottet in einem schalldicht verkleideten Zimmer, um fern des großstädtischen Lebens seine »Recherche« zu schreiben. Das wäre künstlerisch gesehen einmal das Verhältnis von Teilnahme und notwendiger Distanz. Aber ist es andererseits heute noch möglich, sich derart von der Wirklichkeit abzuschotten? Gibt es überhaupt noch Privatheit in der scheinbar totalen Jetztzeit unserer Gegenwart?

TP: Privatheit wird in jedem Lebensbereich suggeriert. Man tauscht sich aus in Chats, auf Dating-Seiten, kriegt über jede App einen direkten Zugang zu seinen Sehnsüchten oder Wünschen. Auf der anderen Seite wird jeder Anruf zum Affront. Privatheit ist wichtiger denn je, aber ohne den Filter der Ablenkung. Man ist nicht mehr gewöhnt, sich ungeborgen zu fühlen. Das Smartphone gibt mir das Gefühl, dass ich nicht mehr allein sein kann. Der Filter der Ablenkung ist immer da. Das Gefühl der Gegenwart wird schwammiger, wabernd, obwohl doch alle Angebote unseres alltäglichen Lebens darauf abzielen, dass wir uns in dieser ›totalen Jetztzeit‹ fühlen, von der du gesprochen hast. Prousts »Insular State« ist radikal und das hat natürlich einen Reiz in einer Zeit, in der man in jeder Dimension digital umarmt wird.

CM: In den vergangenen Jahren hast du dich mit dem Boulevard, der ›Yellow Press‹ beschäftigt. Wie kam das?

TP: Ich interessiere mich sehr für Anerkennung als soziales Phänomen. Mich faszinieren auch Schauspieler und ihre Aura. Der Boulevard stellt eine Nähe zu diesen Stars her … und gleichzeitig die größtmögliche Distanz. Aus der Sicht eines Fans zahlst du eine Zeitung, um in die Lebenswelt fremder Menschen einzutauchen. Jeder aktive Impuls wird zugunsten einer passiven Fan-Perspektive unterdrückt. Dagegen kann ich mit meinen ›Celebrity-Bildern‹ andere Verhältnisse herstellen und mir die Stars zu meinen Gunsten aneignen. Die Bilder aus der aktuellen Ausstellung sind alle aus der BILD-Zeitung abfotografiert. Die BILD hat die meisten Farbfotos und ist für mich nochmal härter als die anderen Gossip-Zeitschriften, mit denen ich zuvor gearbeitet habe. Die BILD will vor allem, dass es visuell knallt. Und da wird es für mich als Maler interessant. Andererseits ist das Papier der Zeitung sehr stumpf und billig. Da gibt es eine Fallhöhe, an der ich mich abarbeiten kann. Dazu mag ich, dass der Boulevard und die BILD ihr Vorbild in England haben. Das passt wieder zu »Insular State« … Natürlich wollen der Springer Verlag und die BILD-Zeitung auch nichts anderes, als aus einem größtmöglichen Publikum eine abgeschlossene Gesellschaft zu schaffen.

CM: ›England‹ kann ich auch … mit John Donnes »No man is an island / Entire of itself / Every man is a piece of the continent / A part of the main.« Die ›abgeschlossene Gesellschaft‹ künstlerisch also ja, gesellschaftlich aber nein?

TP: Ich glaube, gesellschaftlich schafft oder sucht man abgeschlossene Gesellschaften oft aus Angst oder Bequemlichkeit. Das Gute für mich an der Kunstproduktion ist, dass ich dort einige defizitäre Anteile verarbeiten kann. Dazu brauche ich erst einmal einen geschützten Raum. Wenn die Bilder fertig sind, will ich aber, dass sie und ich in den Kontakt mit den Betrachtern kommen. Ich mag es, wenn Ausstellungen ein Ereignis sind.

CM: Dementsprechend gibt es in deiner Arbeit zwei einander beständig zuwiderlaufende Pole: Fragmente von medialen Bildern und ungegenständliche Gemälde. Wie geht das für dich zusammen? Woher kommen die Widerstände?

TP: Wenn Foto und Malerei in einer Ausstellung zusammenhängen, ohne dass das formal oder installativ ›gerechtfertigt‹ ist und eine Hängung wie selbstverständlich stattfinden kann, finde ich das erstmal spannend. Und die Fotos und die Malerei sind beide gestisch und expressiv. Manchmal habe ich das Gefühl, in der Malerei genau in die Oberfläche eindringen zu können, die die Fotografie so stark voranstellt: Ein Widerspruch, der sich für mich ergänzt.

CM: Bilden die Handgeste Angela Merkels, die Füße von Manuel Neuer, ein Kreuz in bayrischen Schulklassen, grimassierende Politiker oder eine Katze ein brüchiges Mosaik der Gegenwart?

TP: Mir ist aufgefallen, dass die BILD-Zeitung sehr viele Hände und Gesten abbildet. So ist es zu den vielen Körperfragment-Fotos gekommen. Die Füße von Neuer transportieren für mich diese sich immer wiederholende Konzentration und Disziplin eines Sportlers, etwas was ihn ›insular‹ macht und von anderen Menschen trennt. Merkels Hand drückt einfach Macht für mich aus. Wie Springer auch, bei dieser ganzen Kreuz-Kampagne fand ich inhaltlich erstaunlich, wie Söder und die BILD zusammengearbeitet haben. Außerdem wird das Kreuz in meinem Foto fast zu einer schwebenden Waffe. Das ist doch gut.

CM: Wenn die Fotos inszenierte Machtdemonstrationen sind, die du dem Boulevard gewissermaßen enteignest und dann visuell sezierst, was sind dann die Gemälde?

TP: Sowohl die Fotos wie die Malereien sind ja Bilder. Viele Elemente der Fotos kommen in den Malereien vor und umgekehrt. Ich glaube, dass die Malereien ikonisch dastehen können und trotzdem auf eine dauernd fortwährende Übung verweisen. Die Malerei hat für mich viel mit Charakter und Haltung zu tun.

CM: Mir kommt es so vor, als ob der bewegt verwobene Gestus ihre bewusste Setzung zu verhüllen scheint. Und gegenüber den ausschnitthaften Medienbildern, die grell und vulgär erscheinen, sind sie doch eher zurückgenommen, still und beinahe kontemplativ gestimmt.

TP: Da hast du Recht. Ich fände es ja super, wenn ich einfach nur eine monochrome Fläche malen könnte. Obwohl ich so expressiv male, gibt es diesen Wunsch, einfach nur eine einzige Fläche zu haben – wie eine Wand. Ein sich wiederholender Rhythmus, der sich gegenseitig fast aufhebt, genau wie in dem Horrorfilm »The Shining«. Da glaubt man ja auch erst, dass Jack Torrance, der Schriftsteller, den Jack Nicholson spielt, seinen neuen Roman schreibt. Bis die Kamera nähertritt und wir sehen, dass er schon seit Stunden denselben Satz in die Schreibmaschine tippt. Den Satz habe ich vergessen, aber der Vorgang hört nicht auf, mich zu faszinieren.

CM: Wegen dieser faszinierend hermetischen Kontemplation auch die Performance zur Eröffnung?

TP: Während der Eröffnung isst ein in einen Smoking gekleideter junger Mann an einem runden Tisch einen Baumkuchen und trinkt Tee. Er ist allein und diese Teestunde ist ein die Eröffnung zersetzendes Ritual. Er braucht das Dekadente, um sich sicher zu fühlen. Er nimmt weder die Bilder noch die Ausstellungsgäste wahr. Er könnte diese Teestunde auch im Baumarkt oder am Flughafen abhalten. Ich habe viel Verständnis für ihn und bin trotzdem froh, dass er eine Figur bleibt.

All Work And No Play Makes Jack A Dull Boy

Thomas Poschinger in conversation with Christian Malycha

CM: You said that the title of your exhibition – »Insular State« – goes back to Proust, who, after his mother’s death, completely withdrew into the sphere of the private. Even though he lived right in the centre of Paris, he spent all his time isolated in a soundproof room in order to concentrate on his »research« far away from the metropolitan bustle. Approaching this from the perspective of artistic creation, this draws on the interrelation between participation and necessary distance. Is it still possible today to so completely draw back from one’s own reality? Is there any such thing as privacy in the seemingly total now-ness of your present times?

TP: Every aspect of our lives suggests privacy. We create connections in chats, on dating sites, we are offered direct and immediate access to our desires and wishes via app. On the other hand, every phone call seems to be taken as an affront. Privacy is more important now than it ever was before – but without the filter of distraction. We are no longer used to feeling insecure. The smartphone makes me feel as if I simply cannot be alone anymore. Distraction is at hand at all times. Our sense of presence becomes vague, swirling, even though everything in our lives is targeted towards this feeling of ›total now-ness‹ you were talking about. Proust’s »Insular State« is radical and of course this has great appeal at a time when we live in a constant state of digital embrace in every possible way.

CM: Over the last few years you have focused on tabloids, the ›yellow press‹. Why?

TP: I am very much interested in the notion of approval as a social phenomenon. I am fascinated by actors and the aura surrounding them. Tabloids create an intimacy with these stars … and simultaneously the biggest possible distance. From the perspective of a fan, you pay for these papers on order to immerse yourself into the realities of complete strangers. Every active impulse is suppressed in favour of a passive fan-perspective. In contrast to that my ›celebrity-pictures‹ generate very different dynamics; I am able to appropriate these celebrities for my own means. The pictures in this exhibition are all photographed from the BILD newspaper. BILD has the most coloured images and seems to me even more extreme than the other gossip papers I have worked with up to now. BILD is also first and foremost interested in offering a real visual spectacle. And this is where it gets interesting for me as a painter. On the other hand, the printing paper used by BILD is very lusterless and cheap. This means that there is a certain tension I can work off of. I also like that tabloids and the BILD are modeled after the English yellow press. This again alludes to the »Insular State« … of course Springer and BILD have no other aim than to create the largest possible audience and an isolated society.

CM: Well, to take up your reference to England … I’m thinking of John Donne’s »No man is an island / Entire of itself / Every man is a piece of the continent / A part of the main.« Would you approach the notion of an ›isolated society‹ in a positive way artistically, but in a negative way societally?

TP: I think we often seek out isolated societies out of fear or complacency. Artistically, what actually counts for me is that in my art I am able to digest some of the more adverse aspects. And for that, the first thing I need is a safe space. Once the paintings are finished, however, I want them to come into contact with the viewer. I enjoy when exhibitions turn into an event.

CM: This is also why there are two axes in your art that continuously run contrary to each other: fragments of medial pictures and non-representational paintings. How do these two things connect for you? Where do these oppositions come from?

TP: I find it very exciting when it goes without saying that photography and painting can be displayed together in an exhibition and when that does not need to be ›justified‹ formally or within an installation concept. Both the photographs and the paintings are gestural and expressive. Sometimes I even have the feeling that with my paintings I am able to penetrate beyond the surface predetermined by the photos: contradictions which for me complement each other.

CM: Do these individual elements – Angela Merkel’s hand gestures, Manuel Neuer’s feet, Christian crosses in Bavarian schools, grimacing politicians and a cat – create a brittle mosaic of today’s world?

TP: It struck me that BILD uses a lot of hands and gestures. This is how the many photos depicting bodily fragments came into being. Neuer’s feet transport an athlete’s constantly recurring focus and discipline; something which makes him insular and which separates him from other people. Merkel’s hands simply express power for me. Just like Springer, and concerning the whole cross-campaign I found it astounding how Söder and BILD worked together conceptually. Moreover, the cross is turned into a floating weapon in these photos. I think that’s good.

CM: So if these photos are staged demonstrations of power, which to some extent you re-appropriate from the boulevard press and which you visually dissect, how can we then approach the paintings?

TP: Both the photographs and the paintings are images. Many of the photos’ elements reappear in the paintings and the other way around. I think that the paintings may be able to offer us iconic representations and at the same time refer to a continuous practice. Painting for me has a lot to do with character and attitude.

CM: I often feel like as if the paintings’ moving and interwoven gestures disguise their very conscious positioning. And in contrast to the more cut-out character of the media photographs, which appear garish and vulgar, the paintings seem more reserved, quiet and almost contemplative.

TP: Yes, I think you’re right. I would love it if I could just simply paint a monochrome surface. Even though my painting is very expressive, sometimes I wish I could just have one single piece of flat expanse – like a wall. Repetitive rhythms which almost cancel out each other, just like in the horror film »The Shining«. Here, you believe that the novelist Jack Torrance, played by Jack Nicholson, is writing his new book. But then the camera moves closer and the viewer realizes that he has been typing the same sentence over and over again for the last hours. I cannot recall the actual sentence but the process of repetition does not cease to fascinate me.

CM: Is this fascinating hermetic component then the reason for the performance during the opening of this exhibition?

TP: During the show’s opening, a young man dressed in a tuxedo sits at a round table, eats Baumkuchen, and drinks tea. He is alone and this tea time functions as a ritual that deconstructs the opening. He needs decadence in order to feel safe. He perceives neither the pictures nor the visitors. He could just as readily take his tea at the airport or a hardware store. I sympathize with him but at the same time I am glad that he remains a character within the performance.

translated by Jennifer Leetsch