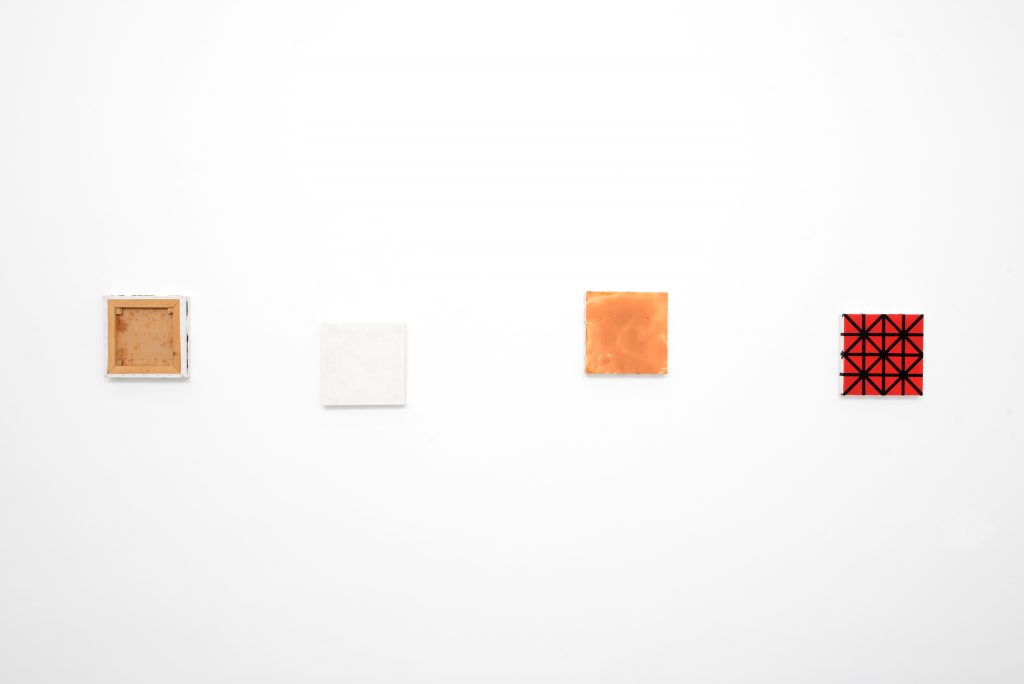

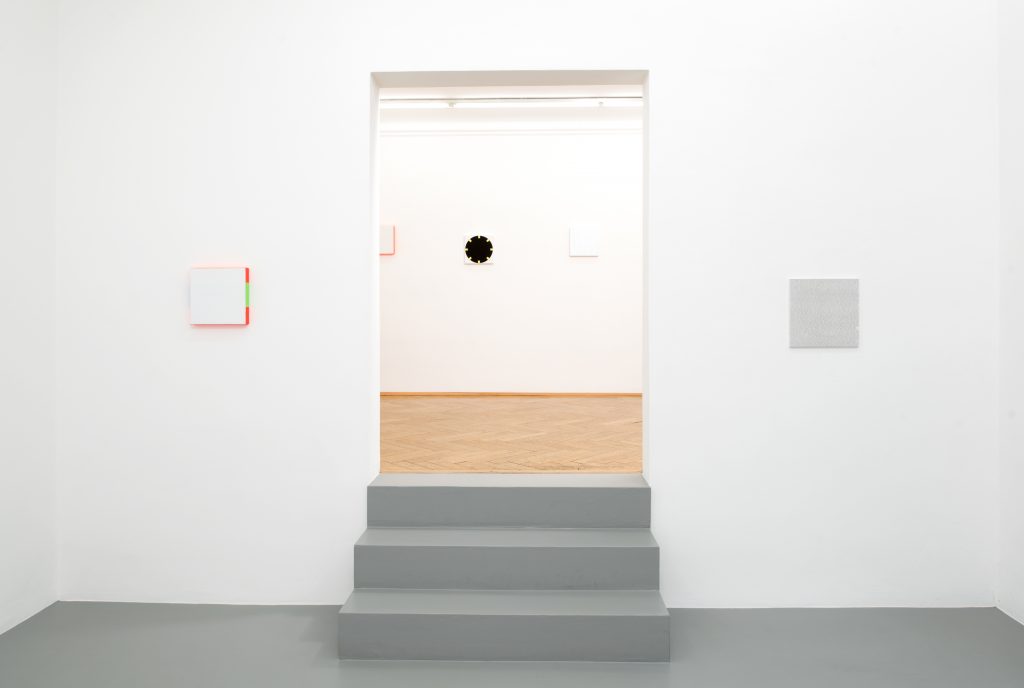

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

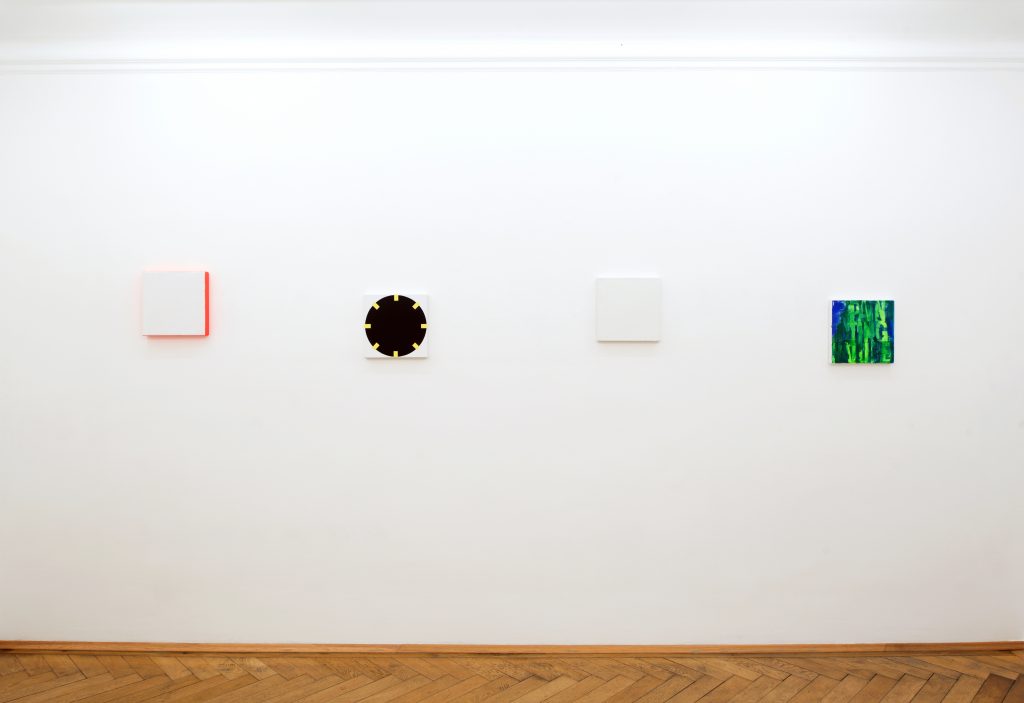

Untitled, 1988

Oil on canvas

30 x 30 x 5 cm

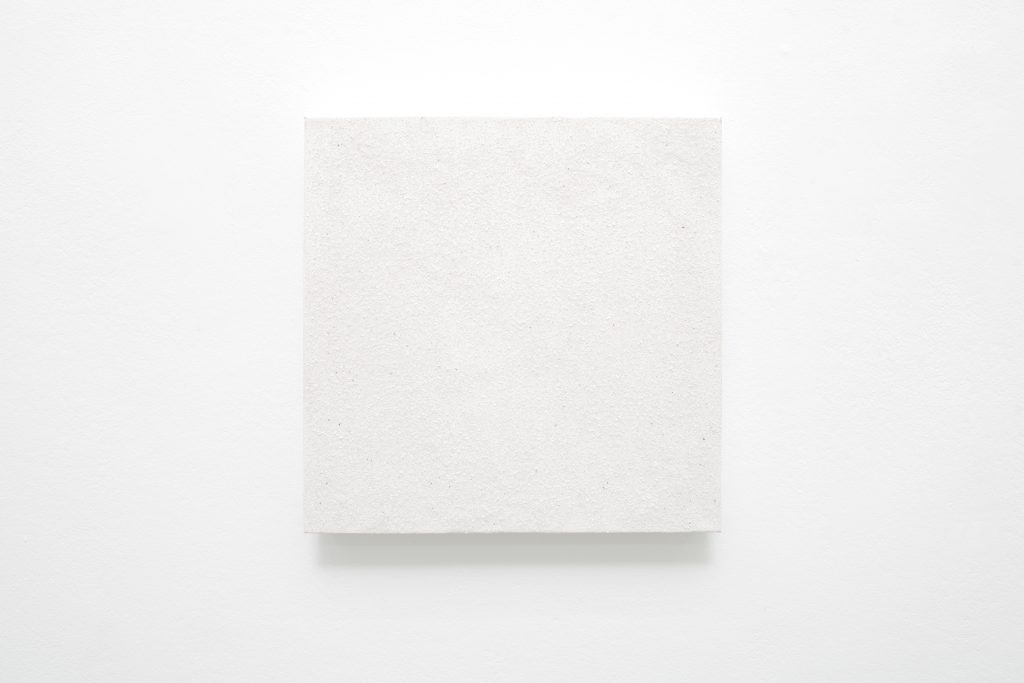

Untitled, 2002

Glas granulate and acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

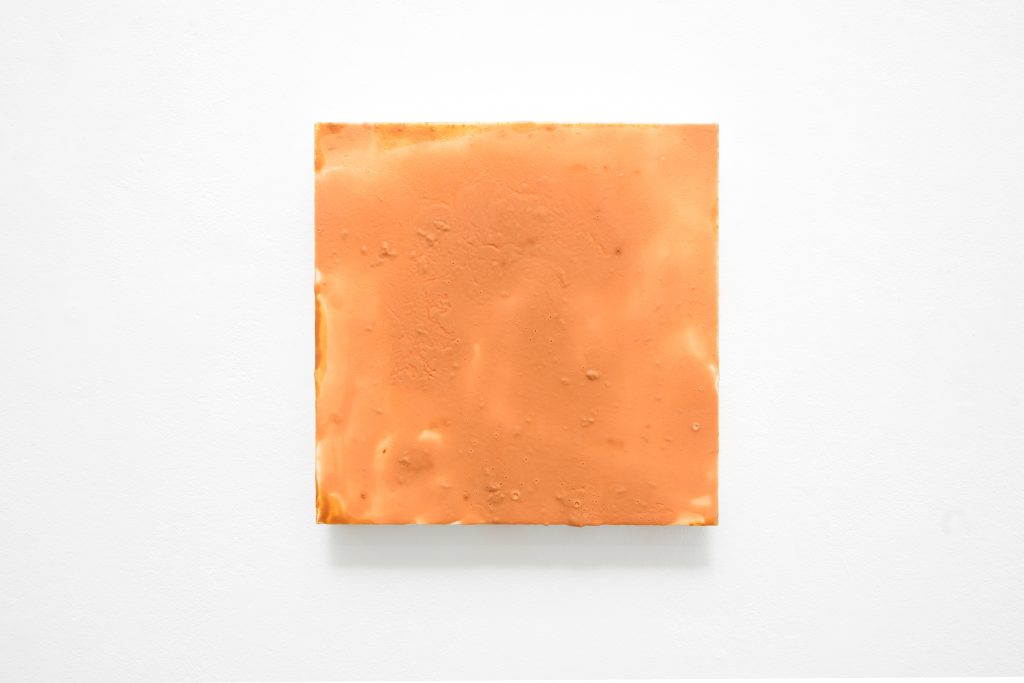

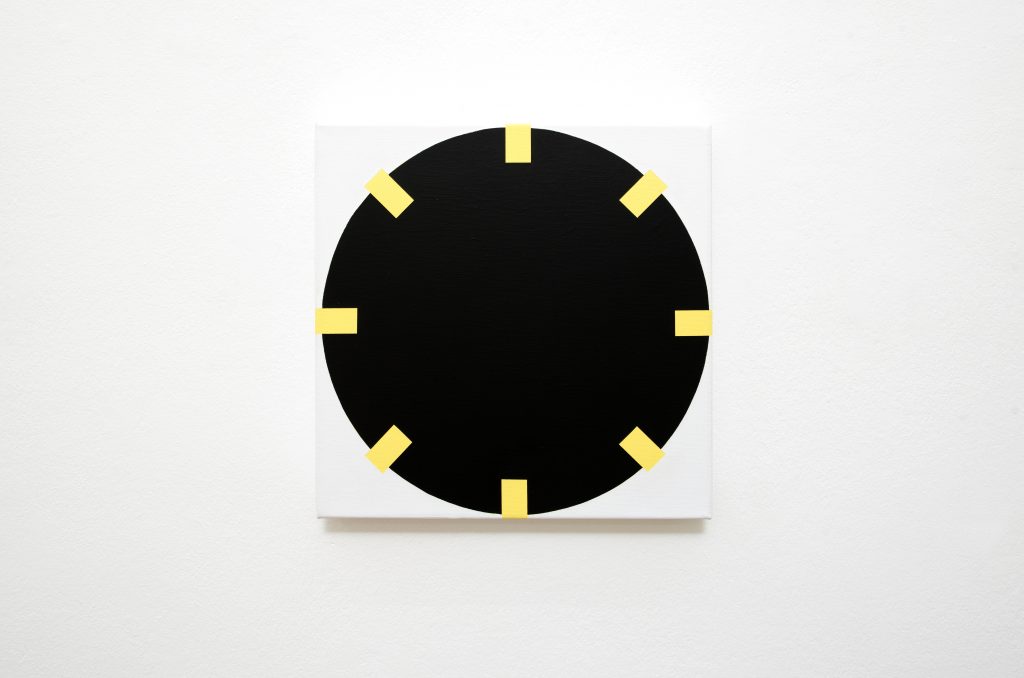

Untitled, 2006

Latex on canvas

30 x 30 cm

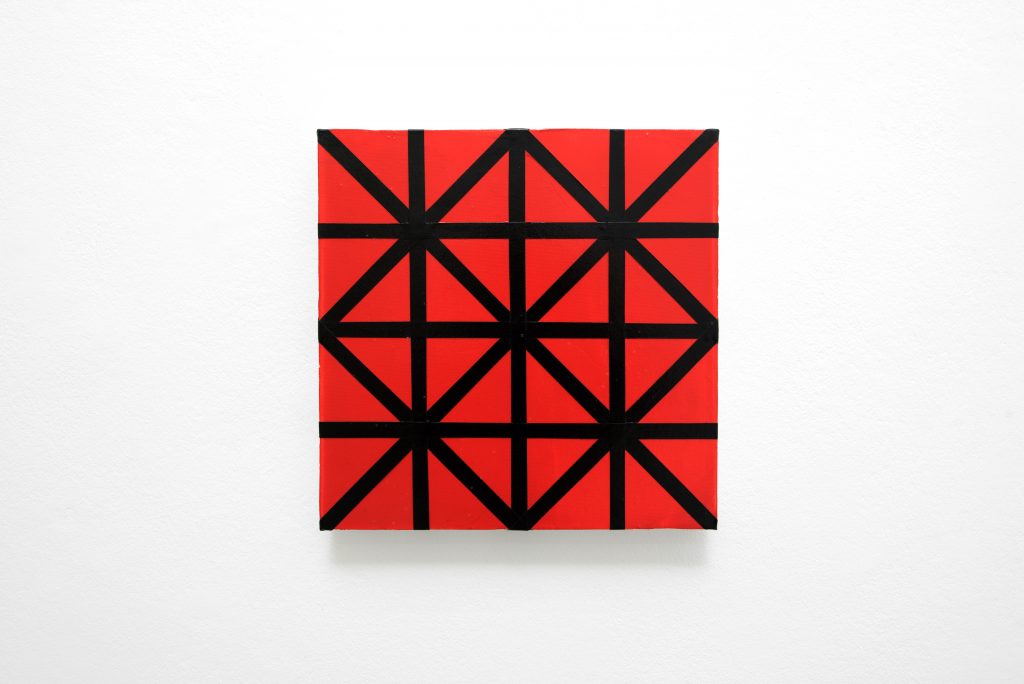

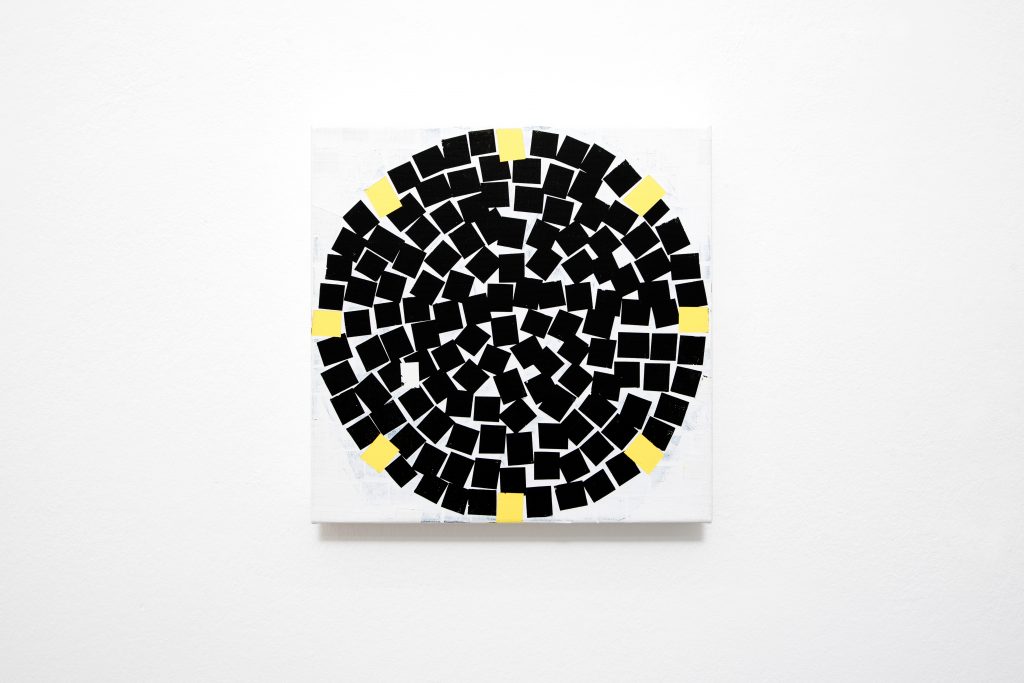

Untitled, 2008

Acrylic binder, tape and acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Installation view

Untitled, 2014

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2016

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2018

Gemstones and acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

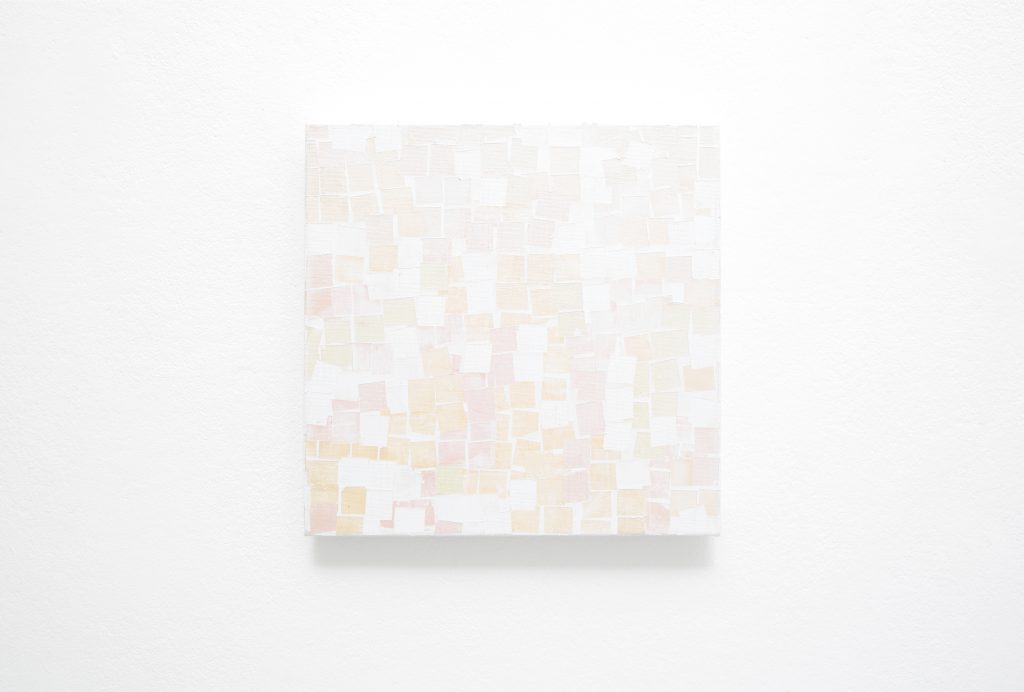

Untitled, 2021

Interferenz Crystal Acryl on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Installation view

Untitled, 2021

Acrylic, video blue, video red, greenbox Trevira Television CS, canvas

30 x 30 cm

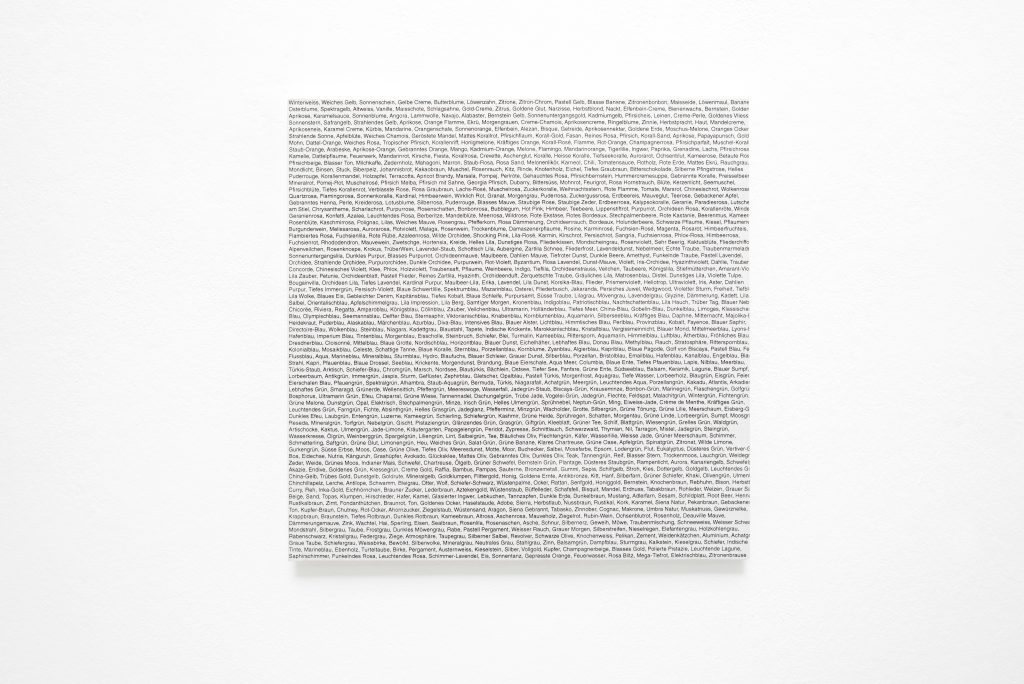

Untitled, 1999

Photo copy, paper, MDF

36 x 36 cm

Edition 1/1-3/3, 1/1 EA

Installation view

Untitled, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Installation view

Untitled, 2021

Interferenz Crystal Acryl, video red Trevira Television CS

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2020

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2021

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 30 cm

Untitled, 2021

Acrylic, video red Trevira Television CS

30 x 30 cm

Graw: Dir selbst ging es aber doch nie primär um sinnliche Erfahrung?

Zobernig: Unbedingt und in erster Linie. Das ist mein Ausgangspunkt.

Wenn die Kunst spricht. Ein Interview von Isabelle Graw mit Heimo Zobernig, in: Kunst und Text, Leipzig 1998, S. 57f.

Wenn ich Kunst und Text, eine Publikation, die ich 1999 im Kunstverein München erworben habe, heute aufschlage, dann treten die Kunst und die Texte weit auseinander: Was ich sehe, kommt mir jetzt noch stärker als vor 20 Jahren entgegen. Was ich lese, kommt mir dagegen vor wie ein Winken zum Abschied. Annelie Pohlen spricht von einer „Ausstellung als Kunst“, in der am Ende nichts Materielles stehen bleibt, sondern nur Geistiges, „welches sich dem materiell Gestalteten ob seiner im Rezipienten wirksamen Projektionen verdankt.“ Jan Winkelmann spricht von „intuitiven Formalismen“, die sich außerhalb der Intuition nicht als Abstraktionen darstellen, sondern als Reduktionen. Dirk Snauwaert fasst „Universalismus, Globalismus, eine Bibliografie“ ins Auge und interpretiert sie mit den ironischen und doch nicht lustigen Worten, „dass gerade die Bürokratie das Ende aller revolutionären Bewegungen dieses Jahrhunderts war.“ Schließlich können der Künstler selbst und Isabelle Graw schon miteinander reden, aber sie „können“ das nur, wirklich oder aktuell reden sie aneinander vorbei. Einmal sagt Zobernig: „Der Bedarf ist damals wie heute der gleiche. Nur Fomulierungen werden neu aktualisiert.“ Das ist doch etwas ganz anderes als die Vorgaben und die Wertungen, die für Graw aktuell oder heute bestehen! Dass sich Produktion und Rezeption, Behauptung und Reduktion, Gedächtnis und Archiv, Möglichkeit und Wirklichkeit so weit voneinander entfernen, lässt nicht an der Kompetenz der Schreibenden zweifeln. Die Frage ist vielmehr, ob das Schreiben selbst etwas anderes sein kann als ein Winken zum Abschied.

Die Bilder, die Heimo Zobernig für seine Ausstellung in der Galerie Christine Mayer 2021 ausgewählt hat, lassen auch die 1998 vorgeschlagenen Begriffe neu überdenken. Die Leinwände können zweifellos Projektionsflächen bilden für die Betrachtenden: Auf einem der Bilder steht „LOOK“, in anderen finden Interferenzfarben Verwendung, die sich ändern, wenn jemand vorbeigeht. Es stellt sich auch die Frage, ob und wie die Bilder abstrakt sind: Einige enthalten Buchstaben, eines lässt an eine Uhr oder an einen Kompass denken. Die durchgehend 30 x 30 cm großen Arbeiten stammen aus verschiedenen Jahren und können zusammen gelesen werden als kleines Archiv: Die früheste mit der Jahreszahl 1988 besteht aus zwei Leinwänden auf Rahmen, deren Vorderseiten durch Farbe zusammengehalten werden, so dass nur sichtbar bleibt, was normalerweise hinten ist. In den Bildern von 2021 dagegen ist schon sichtbar, was vorne drauf ist: „PAINTING NATURE“, „INFRASTRUCTURE NATURE“. Ich denke an einen Satz, den Zobernig auf Sexualität bezieht: „Es geht zum Beispiel um Verdecken oder Sichtbarmachen.“ Und schließlich handelt es sich ganz sicher um eine Aktualisierung, wenn die Ausstellung genau 20 Jahre nach dem ersten Auftritt des Künstlers in der Galerie Christine Mayer stattfindet.

Die Frage, ob ein Text eine Kunst einholen kann, stellt sich neu, wenn diese Kunst von sich aus den Text wiederholt, für den sie vor mehr als zwei Jahrzehnten der Anlass war. Das bedeutet nicht, diesen Text zu verkürzen. Heimo Zobernigs Kunst wird umgekehrt zum Ausgangspunkt, um den Text zu vertiefen. Jan Winkelmanns Rede, dass bei Zobernig nicht Abstraktion, sondern Reduktion vorliege, kann verkürzt auf das Ende zulaufen, dass nichts Neues mehr zu erwarten sei. Die gleiche Rede kann aber auch Immanuel Kants Inauguraldissertation von 1770 aufrufen, wo es heißt: „Eigentlich sollte man nämlich sagen: ‚von etwas abstrahieren‘, nicht: ‚etwas abstrahieren‘“. Es ist hier nicht die Frage, ob Formen, Farben, Räume, Reden und Klänge der Erfahrung nur folgen oder schon vorher bestehen, wie genau das eine das andere hervorbringt oder auch umgekehrt. Denn Heimo Zobernigs Arbeit will so wenig wie Kants Kritik eine Philosophie sein, die sagt, wie es wirklich ist. Vielmehr stellt sie auf ihre Weise die Frage nach der „Bedingung der Möglichkeit“. In der Kunst kann diese Bedingung nur materiell sein.

Berthold Reiß

Graw: Dir selbst ging es aber doch nie primär um sinnliche Erfahrung?

Zobernig: Unbedingt und in erster Linie. Das ist mein Ausgangspunkt.

Wenn die Kunst spricht. Ein Interview von Isabelle Graw mit Heimo Zobernig, in: Kunst und Text, Leipzig 1998, S. 57f.

When I open Kunst und Text today, a publication I acquired at the Kunstverein München in 1999, the art and the texts stand wide apart. On the one hand, what I see strikes me even more strongly now than it did 20 years ago. What I read on the other hand, seems like a wave goodbye. Annelie Pohlen speaks of an “Ausstellung als Kunst” in which at the end nothing material remains, only the spiritual, “which owes itself to the materially designed because of the projections effective in the recipient.” Jan Winkelmann speaks of “Intuitive Formalismen” that do not present themselves as abstractions outside of intuition, but as reductions. Dirk Snauwaert envisages “Universalismus, Globalismus, eine Bibliografie” and interprets it with irony yet without humour, ” that bureaucracy was precisely the end of all revolutionary movements of this century.” Finally, the artist himself and Isabelle Graw may indeed have been able to talk to each other, but they “can” currently only really talk past each other. At one point Zobernig says: “The need is the same then as now. Only the formulations are updated.” That is something quite different from the specifications and the valuations that exist for Graw currently or today! The fact that production and reception, assertion and reduction, memory and archive, possibility and reality are so far apart does not cast doubt on the competence of the writers. The question is rather whether writing itself can be anything other than a wave goodbye.

The paintings Heimo Zobernig has chosen for his exhibition at Galerie Christine Mayer 2021 also make us reconsider the terms proposed in 1998. The canvases can undoubtedly form surfaces for the projections of the viewers: One of the paintings says “LOOK”; others use interference colours that change when someone walks by. There is also the question of whether and how the images are abstract: Some contain letters, one makes you think of a clock or a compass. The works, which measure 30 x 30 cm throughout, date from different years and can be read together as a small archive: The earliest, dated 1988, consists of two canvases on frames the front of which is held together by paint, leaving visible only what is normally at the back. In the paintings from 2021, on the other hand, what is on the front is already visible: “PAINTING NATURE”, “INFRASTRUCTURE NATURE”. I’m thinking of a sentence Zobernig refers to sexuality: “It’s about concealing or making visible, for example.” And finally, the exhibition is most certainly an updating, as it takes place exactly 20 years after the artist’s first appearance at Galerie Christine Mayer.

The question of whether a text can catch up with art is raised anew when this art repeats of its own accord the text for which it was the occasion more than two decades ago. What this does not mean, is a reducing of the text. Heimo Zobernig’s art, conversely, becomes the starting point for deepening the text. So Jan Winkelmann saying, that in Zobernig’s work there is not abstraction, but reduction, may seem to conclude that nothing new can be expected. The same speech, however, can also invoke Immanuel Kant’s Inaugural Dissertation of 1770, where it says “for properly we should say abstract from some things, not abstract something.” The question here is not whether forms, colors, spaces, speeches, and sounds merely follow experience or already exist before it – how exactly the one produces the other or even vice versa. For Heimo Zobernig’s work wants to be a philosophy that says how things really are as little as Kant’s Critique. Rather, in its own way, it poses the question of the “condition of possibility.” In art, this condition can only be material.

Berthold Reiß

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version), edited by Magdalena Wisniowska