Das Zeichen und die Göttlichkeit sind am gleichen Ort und zur gleichen Stunde geboren. Jacques Derrida.

Munich Sentimental könnte eine Rückkehr bedeuten an den Ort, an dem alles begann. Die Ausstellung würde dann verwerfen, was Marc LeBlanc festhält: Jeder Werkzyklus wird von einem neuen Künstlercharakter vorgeführt, und wenn Mayer dessen müde ist, sieht man nie wieder etwas davon. Derselbe LeBlanc aber nennt Tabu und Tod, das Verworfene im Großen und Ganzen. Es heißt: Wenn es eine Kontinuität gibt, dann liegt sie in dem, was Mayer malt.

Diese Kontinuität aber käme ohne den Künstler aus wie der Mond, der angezogen und nach außen bewegt wird und dadurch stabil auf Abstand gehalten. Entsprechend spricht Isabelle Graw von dem Schweigen, welches die Frauen in den Bildern von Hans-Jörg Mayer umhüllt. Als ob die Bilder Tatsachen wären und doch nicht Werbung und Nachrichten. Als ob sie nur dazu verführen könnten, Stücke der Welt zu verwerfen. 2022 hat jemand in der Galerie Christine Mayer es so viel wie abject, verwerflich genannt, dass Mayer überhaupt eine Frau malt und erst recht eine Frau als indische Göttin. Kein Anderer als Hans Sedlmayr wird der Sprecherin genauso gerecht wie dem, was sie vorbringt: Allgemein dürfen Kunstwerke nicht gemessen werden an dem, was sie darstellen.

Abjekt ist das Verworfene, das aber spricht. Ohne Wenn und Aber kann sich das gleiche nur als Welt darstellen, die aber schweigt. Die Analyse, unter der die Welt in Tatsachen zerfällt, wird immer umgekehrt werden in der Synthese. Auch in der Analyse, die zögert, sich durchzustreichen, kommt das Bild zu dem hinzu, was entweder philologisch oder geometrisch gesagt werden kann. 1988 heißt es im Katalog einer Gruppenausstellung im Kunstverein München zu Hans-Jörg Mayer: Zur Sprache und geometrischen Form kommt als drittes, wesentliches Element das Bild hinzu. Aber das, was Kant synthetische Erweiterung nennt, geht darüber hinaus. Es kommt zu dem Abschluss hinzu, der in der analytischen Erläuterung bereits vorliegt.

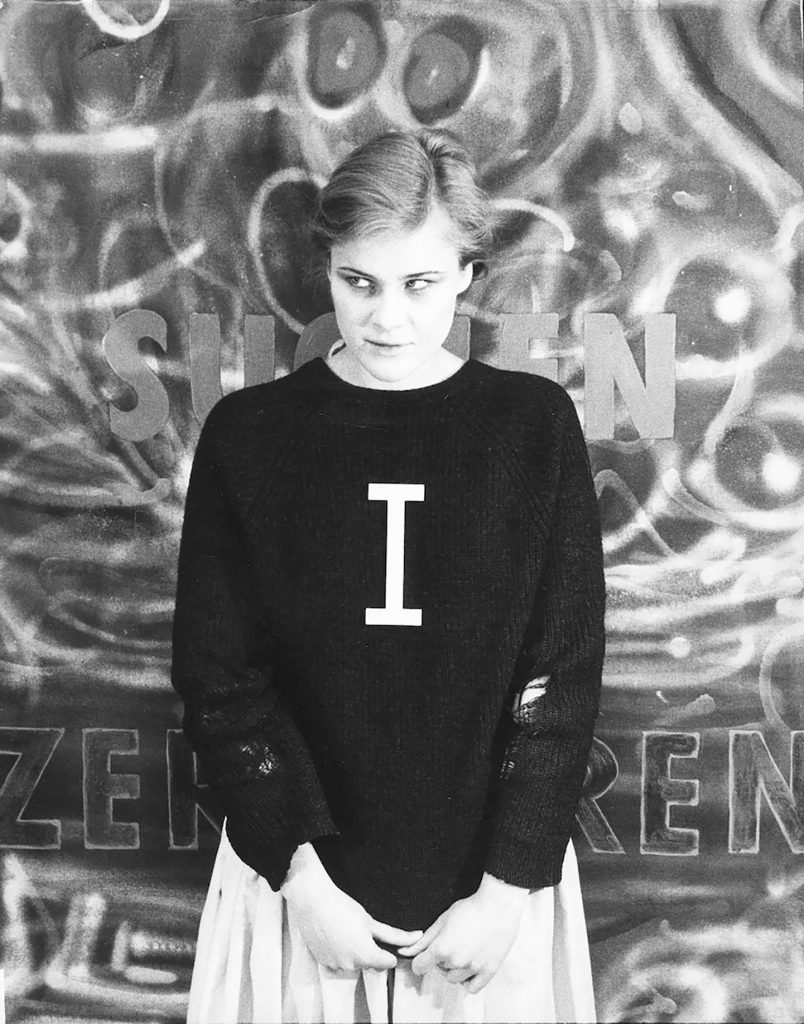

Das, was hinzukommt, ist daher ein Anfang, aber kein Ursprung. Hans-Jörg Mayer berichtet, dass er zuerst Wörter und Zeichen gemalt habe, weil ihm an der Akademie in München gesagt wurde, dass er nicht malen könne. Sogar die in Berlin entstandenen Gemälde sind als Malerei so wenig akademisch wie möglich. Institutionell könnte nur sein, die Fotografie als solche eine Institution zu nennen. Und sicher ist nur, dass diese Sicherheit nur zu ertragen sein wird mit der Versicherung, dass die zu einem großen Teil fotografischen Vorlagen doch feuchter Quellgrund seien oder lebendiger Ursprung.

Zu sagen, dass Munich Sentimental sich auf L. A. Confidential beziehen lässt, dass das eine eine Ausstellung ist und von 2025 und das andere ein Film und von 1997, ist im besten Falle verschwiegen. Zu sagen, dass sich mit einem Standort auch Emotionen verbinden, stiftet keine Einheit und schafft keinen Überfluss. Dagegen ist in dem Katalog des Kunstvereins von 1988 vielleicht mehr gesagt als gemeint, wenn es heißt, dass die sprachlichen Mitteilungen bei Hans-Jörg Mayer nicht als Verweise auf mögliche Bildinhalte funktionieren. Die Ausstellung in der Galerie Christine Mayer kann auf fast 40 Jahre verweisen. Dennoch meint Munich Sentimental nicht Anfang und Ende oder Geburt, Sex und Tod. Diese Worte waren 1985 in einem Bild von Hans-Jörg Mayer genannt oder angebracht. In dem Titel G. S. T. sind sie abgekürzt. Schon damals waren die Lettern Überschuss oder Design, und es verbarg sich dahinter nichts, was nur wichtig ist, weil es allen auferlegt ist. Designiert werden Mann und Frau nicht als Vater und Mutter, aber als Vorsitzende.

In der Ausstellung Munich Sentimental sind die Arbeiten von 2022, 2023 und 2025 sofort als Bilder zu identifizieren. Ihre Titel jedoch verweisen vor allem auf das, was zu ihnen und mehr noch zu ihren Gegenständen hinzukommt. BOOSTER zeigt 2025 die teuerste Handtasche, und der Titel bedeutet so viel wie Verstärker, Rakete und Aufheller. Aller Voraussicht nach wird das Bild nicht den Preis von 500.000 Euro erzielen. Aber wie kann es um Erfolge gehen wie diesen? Wäre das Ziel erreicht, dann wäre der Künstler nicht länger gefesselt, sondern besiegt. Siegen würde das, was Mayer malt. Die Kontinuität, die LeBlanc darin liegen oder verborgen sieht, findet ein Ende als Anfang und doch nicht als Ursprung.

Daher kann Hans-Jörg Mayer das, was er malt, auch ausstellen. 1988 war im Kunstverein München der Aluguss BLONDE zu sehen. 2025 aber versammelt Munich Sentimental die Güsse BONUS, $55,95, 2FOR1, SEXX, SWEET, ANGEL, SHADES, FREE FREE und $2. In Aluminium und in Eisen scheint alles gesagt. Das heißt nicht, dass auch alles gezeigt wird. Es heißt vielmehr, dass das Was sich als Schrift darstellt. Diese ist nicht geborgen im Buch und sogar in der Zeit nicht abschließend unterzubringen. Ich erinnere mich an Seiten in Hand und Wort, auf denen André Leroi-Gourhan die Anordnung in der Werbung mit der in der Höhlenmalerei vergleicht. Gewiss hat Mayer in der Hans-Sachs-Straße gearbeitet. Er hat diese Werke 1987 und 1988 in der Gießerei Mayer in der Fraunhoferstraße ausführen lassen. Und er zeigt sie nun in der Liebigstraße in der Galerie Christine Mayer. Aber sollen wir nun von Inschriften reden oder von Bildern? Oder: Warum ist $55,95 sogar noch mehr ein Relief, nachdem der Künstler es mit Ölfarbe übermalt hat?

Alois Riegl hat die spätrömische Kunstindustrie als einen Übergang geschildert, der vom Haptischen zum Optischen hin verläuft. Aber dieser Kurs erweist sich als Rekurs, wenn das Sichtbare auch das Greifbare erneuert hervorbringt. So ist der Verfall der Außenwahrnehmung mit Händen zu greifen, der propagiert wird als Expansion in die Sichtbarkeit. Bleiben wird nur das Bild, das so wenig ein Abbild ist, wie es niemals ein Urbild sein kann. In Munich Sentimental macht Hans-Jörg Mayer erneut lesbar, was Jacques Derrida sagt: Das Zeichen und die Göttlichkeit sind am gleichen Ort und zur gleichen Stunde geboren.

Berthold Reiß

The sign and divinity have the same place and time of birth. Jacques Derrida

Munich Sentimental could signal a return to the place where everything began. The exhibition would then refute Marc LeBlanc’s observation that each group of works is presented by a new artist persona, and that once Mayer has tired of this, it is never seen again. Yet the same LeBlanc talks about taboo and death, the abject at large. Which means that, if there is any continuity, it is found in what Mayer paints.

But this continuity gets along very well without the artist – in this way, similar to the moon, which is both attracted and pulled outward and thereby kept at a stable distance. In this sense, Isabelle Graw speaks of the silence surrounding the women depicted in Hans-Jörg Mayer’s pictures. As if the pictures were facts and not advertising and news. As if they could only tempt us to reject pieces of the world. In 2022, someone in Galerie Christine Mayer described as abject the fact that Mayer painted a woman at all, let alone a woman as an Indian goddess. It was none other than Hans Sedlmayr who paid as much attention to the speaker as to what she propounded: in general, works of art should not be measured by what they represent.

Abject is what is discarded, rejected, but which speaks. It goes without saying, however, that the same can only represent itself as a world, but one that stays silent. The analysis under which the world is split up into facts will always be reversed in synthesis. Even in the kind of analysis that hesitates to cancel itself, the image is added to what can be said either philologically or geometrically. In a catalogue for a group show at the Kunstverein München from 1988, we read in relation to Hans-Jörg Mayer that, in addition to language and geometric form, a third essential element is the image. But what Kant calls synthetic extension goes beyond this. It is added to the conclusion which is already present in the analytic exposition.

What is added is therefore a beginning, but not an origin. Hans-Jörg Mayer informs us that he first painted words and signs because, at the Munich Academy, he was told he couldn’t paint. Even the works made in Berlin are, in terms of painting, as unacademic as possible. Institutionally, the only possibility would be to call photography as such an institution. And the only thing that is certain is that this certainty can only be tolerated with the assurance that the mostly photographic models are, after all, a damp source or living origin.

To say that Munich Sentimental can be related to L.A. Confidential, and that one is an exhibition and from 2025 and the other a film and from 1997, is at best an understatement. To say that emotions are associated with a location gives rise to neither unity nor richness. On the other hand, in the 1988 Kunstverein catalogue, one perhaps finds more said than was intended when we read that the verbal messages in Mayer’s work do not function as references to a possible pictorial content. The exhibition in Galerie Christine Mayer can look back on almost forty years. At the same time, Munich Sentimental does not allude to a beginning and an end, or to Geburt, Sex, and Tod (birth, sex, and death). These words were cited in or affixed to a picture by Hans-Jörg Mayer in 1985. They are abbreviated in the title G. S. T. Even then, letters were surplus or design, and what was hidden behind was nothing, which is only important because it is imposed on everyone. Man and woman are not designated as father and mother but as chairpersons.

In the exhibition Munich Sentimental, the works from 2022, 2023, and 2025 can immediately be identified as pictures. Their titles, however, refer primarily to what is added to them, or rather to their subjects. BOOSTER shows 2025’s most expensive handbag; the title means something like amplifier, rocket, brightener. In all likelihood, the picture will not fetch the 500,000 euros price. But how can it be about successes like that? If the goal were attained, the artist would no longer be captivated but defeated. Triumphant would be what Mayer paints. The continuity that LeBlanc sees lying or hidden there finds an end as a beginning, not as an origin.

It is for this reason that Hans-Jörg Mayer can also exhibit what he paints. In 1988, the Kunstverein München showed the aluminum cast BLONDE. But in 2025, Munich Sentimental brings together the casts BONUS, $55,95, 2FOR1, SEXX, SWEET, ANGEL, SHADES, FREE FREE, and $2. In aluminum and in iron, everything seems to have been said. That does not mean that everything is also shown. It means rather that the what is shown as text. This is not hidden in a book and cannot even be definitively placed in time. I am reminded of the pages in Gesture and Speech in which André Leroi-Gourhan compares the arrangements in advertising with those found in cave painting. Mayer certainly worked in Hans-Sachs-Straße. In 1986 and 1987, he had the works produced in the Gießerei Mayer in Fraunhoferstraße. And now he is showing them in Liebigstraße in Galerie Christine Mayer. But should we speak of inscriptions or pictures? And why is $55,95 even more of a relief once the artist has painted over it with oil paint?

Alois Riegl depicted late Roman art industry as a transition that proceeds from the haptic to the optical. But this course turns out to be a recourse when the visible gives rise again to the tangible. It is like this that the decline of external perception is made palpable, which is propagated as an expansion into visibility. What remains is only the picture, one that is hardly a likeness, just as it can never be an archetype. In Munich Sentimental, Hans-Jörg Mayer once again makes legible what was said by Jacques Derrida: The sign and divinity have the same place and time of birth.

Berthold Reiß

Translated by Benjamin Carter